Contemporary Literature 2013–2025 : From Pandemic to Platform, from Pronoun to Protest—How Fiction Survived the Algorithm and Found New Tongues

From The Professor's Desk

Contemporary Literature 2013–2025

“The centre did not hold—but the sentence did.”

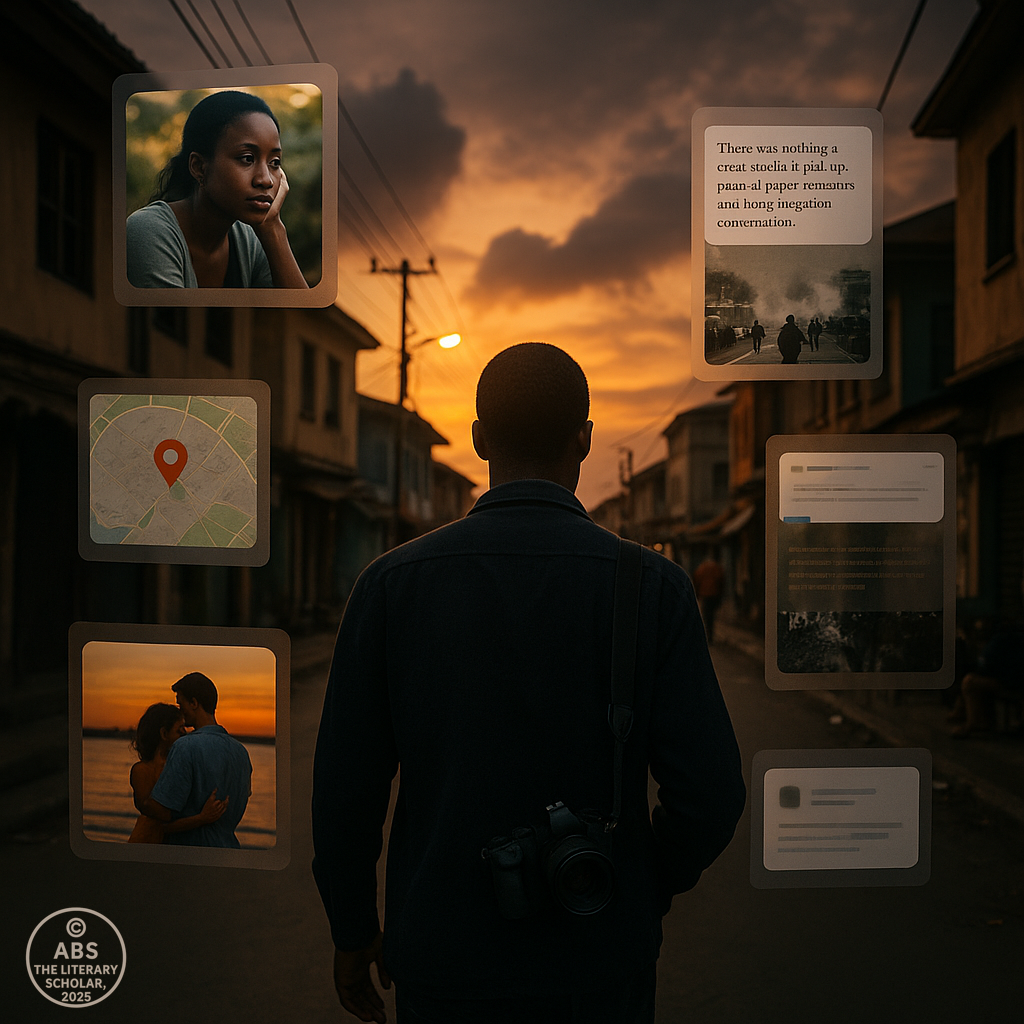

Contemporary Literature 2013–2025, If the first twelve years of the millennium rewired literature’s form, the next decade and beyond tested its nerve, breath, and bandwidth. The period from 2013 to 2025 saw the novel thrown against forces no literary theorist could fully predict—global pandemic, social media dominance, gender revolution, AI co-authorship, and the slow erosion of shared truth. Literature was not just challenged; it was pulverized, pixelated, politicized—and paradoxically, more personal than ever.

This was an age of plural voices. Identity, once background, became narrative architecture. Trauma was no longer theme—it was technique. And the page itself faced extinction, mutation, and rebirth. Stories survived by multiplying. They arrived as autofiction, climate elegy, Instagram poetry, diasporic rage, and Netflix-lured epics. Some whispered in podcasts. Some screamed in slam poetry. Some refused to end.

In the era of infinite scroll, literature asked the most analogue question of all:

“Who’s listening?”

Post-Truth and the Fragmented Narrative

“When facts failed, fiction whispered truth.”

If literature once aspired to be a mirror held up to life, the contemporary novelist found that mirror cracked—not just by complexity, but by deliberate distortion. The years after 2013 did not merely mark a political shift; they heralded an epistemological crisis. What was real? What was manipulated? Who controlled the version that reached the public? In this post-truth era, the novel did not become obsolete. On the contrary—it became the final refuge of coherence in a reality unraveling into curated chaos.

Contemporary Literature 2013–2025 This was the age when world leaders tweeted fiction, and fiction writers tried to piece together truth. The word “narrative” left the classroom and entered newsrooms, boardrooms, hashtags, and battlefields. Everyone was telling a story. And everyone was denying everyone else’s.

Narrative as a Weapon and a Refuge

Post-truth politics (Trump in the U.S., Brexit in the UK, authoritarianism rising globally) turned the writer’s pen into a double-edged instrument—both memoir and resistance, metaphor and document. Language itself seemed suspect, repurposed for spin, ads, bots, and weaponized press releases. In such a moment, fiction was no longer escapism. It became a way to recalibrate reality.

Writers like Ali Smith, with her Seasonal Quartet (Autumn, Winter, Spring, Summer), used fractured timelines and essayistic prose to document Britain’s moral and cultural disarray. These weren’t just novels; they were mood weather reports, publishing almost in real time. What Smith achieved was not plot-driven storytelling, but chronicle-as-catharsis, mixing Brexit headlines with meditations on art, memory, and the passing of seasons.

Narrative Unraveling as Technique

Post-truth demanded post-structure. Fiction abandoned neat arcs in favor of elliptical, episodic, or fragmented storytelling that mirrored the chaos of daily newsfeeds. Consider Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School (2019)—a semi-autobiographical tangle of teenage masculinity, political premonition, and linguistic collapse. Here, toxic language is not merely depicted—it is deconstructed, stuttered, examined, like a wound probed with a scalpel.

Similarly, Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy rejected conventional narrative entirely. Her protagonist is a passive listener, a blank space onto which others project their stories—fitting for an era in which everyone talked, no one heard, and presence meant withholding rather than asserting.

Fiction, in this mode, did not offer a moral. It offered mirrors without frames.

Satire, Irony, and the Deadly Absurd

While some writers disassembled truth gently, others mocked its death with barbed wit. Red Clocks by Leni Zumas imagined an America where abortion is illegal, single motherhood criminalized, and women’s rights dismantled—before such laws began surfacing in real courtrooms. It read like dystopia. And then it didn’t.

Meanwhile, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout (2015), a Booker Prize-winning explosion of satire, portrayed a Black man trying to reinstate slavery and segregation in a fictional LA neighborhood—not as nostalgia, but as violent parody. His absurd logic reveals the even greater absurdity of institutional racism, making us laugh, then recoil.

This was not magical realism. This was bureaucratic surrealism—narratives where systems don’t just fail characters; they erase them with polite efficiency.

Truth as Style, Not Statement

The post-truth era also marked the rise of literature that refused to declare its genre. Memoir or fiction? Essay or novel? Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive blurred these lines beautifully, layering documentary evidence with fictional longing, meditating on migration, motherhood, and memory in America’s morally hollowed landscapes.

Similarly, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? and Motherhood are existential thought-scapes disguised as personal monologues. They ask not what happened, but how to frame what didn’t. Plot becomes irrelevant. Inquiry becomes everything.

In these works, truth is not revealed by the end—it is dismantled with elegance.

The Reader as Investigator

Post-2013 fiction often transformed the reader from a passive recipient into an active decoder. Just as news demanded scrutiny, so did the novel. Unreliable narrators, conflicting timelines, genre-bending voices—these became not gimmicks but epistemological metaphors.

Books like Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann, with its thousand-page single sentence, demanded we submit to thought-overload, much like scrolling through social media. The structure was the story. Reading became an act of willing discomfort.

In an age where lies were louder than facts, literature did not fight fire with fire. It fought chaos with complexity, falsehood with form, and propaganda with the most radical gesture of all—thinking slowly in a world that refused to pause.

Pandemic Literature — Writing Through the Plague Years

“When the world locked down, the sentence broke free.”

The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t just disrupt lives—it cracked open the narrative spine of modern literature. For the first time in a century, a global event was experienced near-simultaneously by the entire planet, and yet no two people lived the same lockdown. The pandemic was both universal and intimate, banal and catastrophic. It turned kitchens into prisons, solitude into screaming, and Zoom calls into existential theatre. And literature—true to its most ancient instinct—began to record.

The Age of the Isolation Novel

The pandemic novel was not merely a genre; it was a genre born in real time. Unlike historical fiction, these books didn’t arrive after retrospection. They emerged while the world was still coughing.

Sarah Moss’s The Fell (2021) is a slim, searing example. A woman in quarantine, trapped in a house with her son, breaks lockdown rules to walk the fells—and vanishes. But Moss is less interested in plot than in mental claustrophobia. The novel reads like a prolonged exhale, unpunctuated by relief. We see the psychic weather of the pandemic—not just fear of disease, but the erosion of civility, sanity, and structure.

Ali Smith, already chronicling the political soul of Britain through her Seasonal Quartet, managed the literary near-impossible: she published Summer (2020) while the pandemic was still unfolding. Her fiction blurred headline and parable, grief and absurdity. The virus did not interrupt her storytelling—it became its natural climax.

Grief as Genre

In the post-2020 literary landscape, grief became its own genre. Not merely emotional content, but structural influence. Books no longer followed arcs of conflict and resolution. Instead, they mirrored mourning’s shapelessness—the disorientation, the silence, the loop.

Hisham Matar’s A Month in Siena and Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air (though written earlier) re-entered the spotlight—quiet meditations on death, legacy, and meaning. The former reflects on the loss of the author’s father amid art and exile; the latter, a dying neurosurgeon’s final reckoning with life’s brevity. These books weren’t “pandemic novels,” but the world read them as pandemic truth.

Memoir in the Time of Mask

The pandemic gave rise to an influx of fragmented, journal-style memoirs. They lacked grandeur but bore visceral immediacy.

Zadie Smith’s Intimations (2020), a collection of personal essays, did not attempt grand analysis. Instead, it offered what literature increasingly prized: honest bewilderment. Smith did not “explain” the pandemic. She simply documented what it felt like to write with a mask on, emotionally and physically.

Meanwhile, Ed Yong, though a science journalist, became an unlikely literary figure—his writing on COVID in The Atlantic read like a well-researched elegy, merging data with despair. Even non-fiction adopted lyric urgency.

Revisiting the Plague Canon

Readers returned to Albert Camus’s The Plague, to Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, and to Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera—not for history, but for prophecy. These works weren’t read as metaphors anymore. They were read as mirrors.

Even Shakespeare became part of pandemic folklore. The widely circulated (and only partially true) claim that he wrote King Lear during a plague lockdown resurfaced, giving writers everywhere impossible expectations and ironic comfort.

Digital Diaries and Epistolary Revival

Another byproduct of the lockdown era was the rebirth of digital diaries, letter-form novels, and email-structured prose. In isolation, humans returned to one-to-one storytelling.

Works like Yiyun Li’s Where Reasons End (2019)—a posthumous conversation between a grieving mother and her dead son—gained renewed resonance. Not pandemic-specific, but suffused with loss that mirrored COVID grief.

Even online, the form evolved. Substack newsletters became serialized personal literature. Blogs reemerged. Instagram captions carried prose-poetry weight. The literary voice migrated where people still met—digitally.

Hope and the Half-Finished Sentence

Some writers did not attempt to end their stories. They left them suspended, like the world itself. The pandemic novel was often not about what happened, but what didn’t. Plans cancelled. Relationships paused. Futures vaporized.

Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020), published as the world began to shut down, is the perfect emblem. It’s not about a pandemic, but it feels like one. The clipped prose, the fragmented insights, the hovering dread of climate collapse and personal unraveling—it’s a prelude to panic, and thus retroactively prophetic.

The pandemic novel did not seek closure. It sought witness—to death counts, to silence, to sourdough obsessions, and to a collective breakdown we’re still pretending we’ve recovered from. In an age of facemasks and false news, literature did not go viral. It went inward.

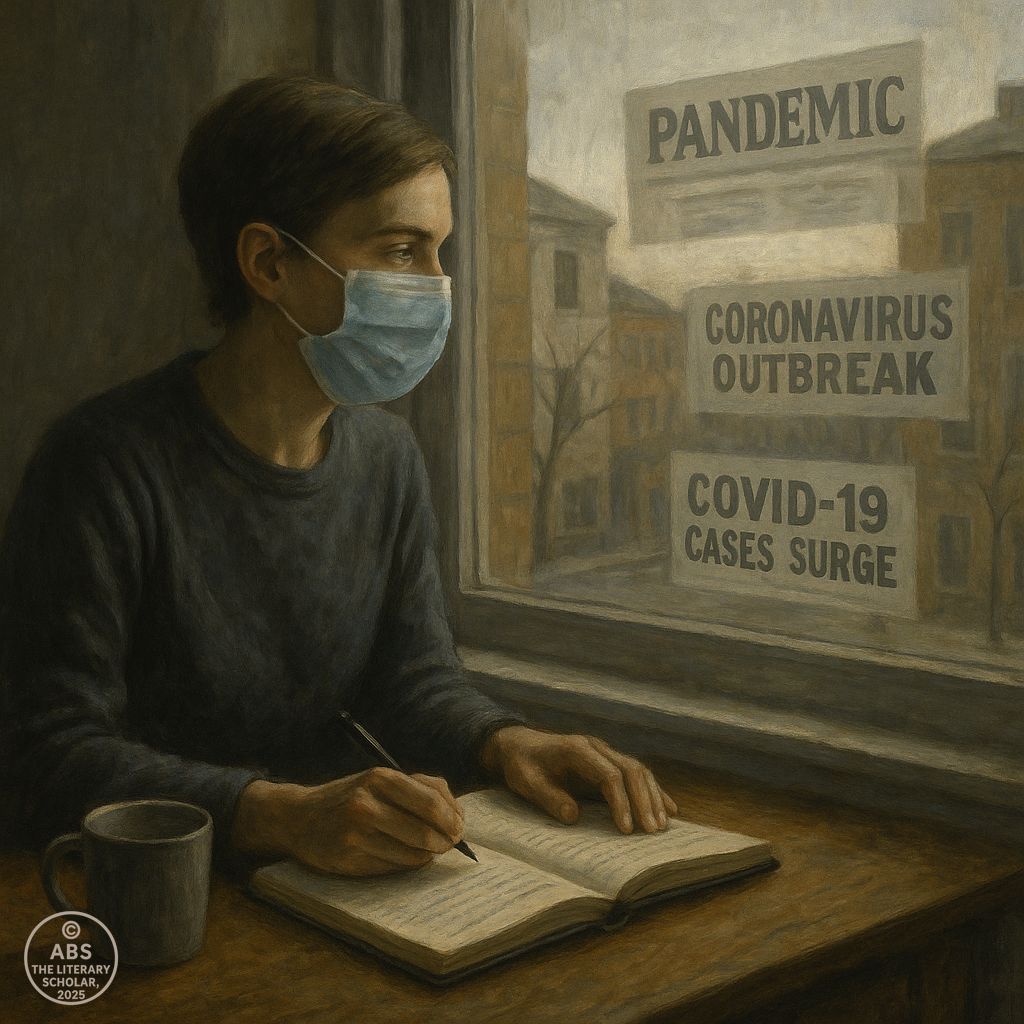

This poignant visual captures the solitary, contemplative spirit of pandemic literature. A lone writer sits masked at their window, staring into the hushed stillness of a locked-down city. Headlines about COVID-19 hover outside, ghostlike. An open journal and cup of tea reflect the turn to inward writing and reflection. It visualizes how literature documented global grief—not through epic plots, but through quiet, personal pages.

Queer, Trans, and Non-Binary Voices — Rewriting the Narrative Body

Contemporary literature has always challenged borders—of genre, nation, form. But over the last decade, a quiet revolution has emerged in the very act of self-narration. Queer, trans, and non-binary writers did not just add new characters to old templates; they rewrote the blueprints entirely—of identity, embodiment, authorship, and voice. What was once token inclusion became something far more radical: a remapping of literature itself around lived plurality.

From Visibility to Structural Reinvention

Earlier decades often relegated queer characters to metaphor or side plot, their identity coded or tragic. The 2013–2025 wave refused both silence and symbolism. Identity was not theme—it was the lens, the sentence, the syntax.

Take Torrey Peters’ Detransition, Baby (2021)—longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and the first by a trans woman to do so. It is not a novel “about being trans,” but about parenthood, longing, messiness, and chosen kinship—rendered through characters who happen to be trans, cis, transitioning, or detransitioning. The structure is complex, the tone irreverent, the moral blurred—because real life is, and trans literature finally claimed that full human mess.

Non-Binary Form for Non-Binary Being

The evolution of form mirrored this gender fluidity. No clean plot. No resolution arcs. No binaries. Many such works operate like open jazz rather than classical sonata—disrupted rhythms, recurring themes, circular memory.

Akwaeke Emezi’s novels (Freshwater, The Death of Vivek Oji, Dear Senthuran) blur autobiography, Igbo spirituality, Western trans discourse, and narrative voice. Emezi, who identifies as non-binary and a spirit, writes not to fit the body into narrative but to let narrative become spirit—shapeshifting, haunting, and at times, uncontainable.

In Freshwater, the protagonist Ada is inhabited by multiple selves, reflecting not just dissociation or trauma, but a cosmic multiplicity. Gender here is not a role but an ontological chorus. Emezi’s work demands the reader unlearn Western binaries and enter a mythic, personal, and cultural hybridity.

The Body as Text, the Text as Transition

In this literary movement, the body itself becomes both metaphor and medium. Just as the trans or non-binary person transitions, so too does the story—becoming itself mid-sentence.

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) stands as a seminal hybrid of memoir, theory, motherhood, queerness, and desire. Blending Roland Barthes with diaper changes, queer kinship with pregnancy, Nelson writes not to explain but to exist on the page—thought by thought, identity by identity. The result is not confessional, but philosophical intimacy.

This is a book of intellectual gender—a space where feelings cite Foucault and love is argued, not declared. And that is its brilliance. Nelson doesn’t offer answers. She expands the frame.

Poetry and the Queering of Language

Language itself—once seen as a neutral tool—was reclaimed as a gendered, colonized, and binary system. Poets began to bend it.

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019), although technically a novel, reads as extended lyric. Addressed to a mother who cannot read, it becomes a letter that only the world can overhear. Vuong’s identity as a queer, Vietnamese American refugee is not footnoted. It is embodied in every metaphor, every breath in the line breaks.

The prose collapses violence and beauty into one breath:

“Let me begin again. Dear Ma, I am writing to reach you—even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are.”

In Vuong’s hands, language itself queers. It detaches from fixed meaning, choosing vulnerability over clarity.

Autotheory, Memoir, and Trans-Textuality

Alongside fiction, we saw the rise of autotheory—where personal narrative and critical theory converge. Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie melds bodily transition (testosterone injections) with philosophical rebellion. Reading it is less about following a narrative and more about being invited into a chemical, political, and literary experiment.

Similarly, Alok Vaid-Menon, performance artist and poet, shattered both page and stage. Their writing is not just identity exploration—it’s linguistic border-breaking, defying grammar and genre with intentional ferocity.

Publishing and the Politics of Space

It must be noted: much of this writing emerged in defiance of traditional publishing gatekeeping. Smaller presses, zines, Instagram poetry, Substack memoirs, and digital journals became the sanctuary spaces for experimentation. The mainstream followed—slowly, and often reluctantly.

But the change is irreversible. Queer and trans literature no longer asks permission. It claims page-space as body-space, and identity as a literary form—not just a subject.

In a world obsessed with declaring what is real, valid, or permitted, queer and trans literature taught us the most radical literary truth of all:

“To write the self is to write the shifting—grammar, body, and genre included.”

The Climate Novel — Writing At The End Of The World

“When the planet screamed, literature finally stopped whispering.”

Literature has always responded to crisis—but never before has the setting itself become the emergency. In the last decade, as climate catastrophes accelerated—wildfires, floods, extinctions, pandemics, plastic-filled oceans—novelists stopped treating the Earth as backdrop. Nature was no longer a passive field on which human stories played out. It became the plot. The antagonist. The wounded narrator.

From realism to speculative fiction, from dystopia to lyric fable, climate change—often coded as “Cli-Fi”—emerged as a genre, a prophecy, and a literary duty. Writers were no longer simply imagining futures. They were documenting the present, before it vanished.

From Awareness to Apocalypse

Earlier eco-fiction whispered. The contemporary climate novel shouts, chants, and sometimes howls. Where the Romantics saw sublime beauty, today’s writers see melting glaciers and choking skies.

Richard Powers’ The Overstory (2018) is a towering symphony of arboreal consciousness—nine characters, each connected by trees, whose lives interweave like roots in a forest. It is a novel of deep time, ecological awe, and radical resistance. Powers doesn’t just write about trees—he lets them speak. The novel ends not with closure, but with canopy: the promise that life will go on—with or without us.

In Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (2012), climate change arrives not through grand disaster, but in the confused migration of butterflies. The protagonist’s small Appalachian world is disrupted by something that seems miraculous but is, in fact, a warning in wings.

Speculative Futures, Real Fears

Contemporary writers also turned to speculative fiction to dramatize the scale of climate trauma.

Omar El Akkad’s American War (2017) imagines a second American civil war in a future ravaged by climate collapse. It is not science fiction—it is a possible tomorrow, disturbingly grounded in today’s divisions.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future (2020) blends fiction, essay, science, and policy into a sprawling, urgent attempt to imagine planetary survival. Unlike dystopias that surrender to despair, Robinson envisions collective resilience. His is not the voice of a novelist alone—it’s a speculative historian of the now.

Indigenous and Non-Western Eco-Literature

Not all climate writing emerges from Western anxieties. Indigenous, African, and South Asian writers bring stories where ecology is identity, not theme.

Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island (2019) continues his quest to foreground the invisible patterns of climate, migration, and myth. The novel weaves Bengali folklore with contemporary climate displacement, refusing the Western tendency to isolate environment from culture.

Ghosh also critiques the literary tradition itself in The Great Derangement—arguing that realist fiction has failed to grasp climate reality because it clings to the plausible, while the planet has entered the improbable.

Similarly, Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves places Indigenous knowledge and ecological harmony at the centre of survival. In her dystopia, Native people are hunted for their ability to dream. It is a metaphor for extractive colonialism and a plea for spiritual ecology.

The Personal as Planetary

Climate novels also became deeply personal, showing how large-scale catastrophe manifests in tiny, human heartbreaks.

Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020) uses clipped, anxious prose to mirror eco-paranoia and emotional inertia. The narrator isn’t saving the planet—she’s scrolling, sighing, panicking over the kettle. This is climate fiction for the helpless middle-class brain, paralyzed by information and fear.

Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible (2020) flips the climate narrative to children—watching their parents fumble in a climate disaster, and realizing they’re better off without them. It’s part satire, part Biblical allegory, part environmental indictment.

Contemporary Literature 2013–2025 : Poetry of Collapse

Even poetry didn’t escape the planetary scream. Writers like Juliana Spahr, Camille T. Dungy, and Craig Santos Perez infused their verse with extinction, oil slicks, melting ice, and ruined reefs.

A single line from Spahr stings more than entire manifestos:

“Some of us tried to love the world. Some of us tried.”

In these verses, nature is not beautiful—it is grieving, gasping, gaslit. And still, the poet writes—not to save, but to mourn, to witness, to warn.

Eco-Fiction’s Moral Dilemma

The question for many climate writers is: What can literature do? Can novels prevent extinction? Can stories reverse carbon?

The answer is no. But they can change the cultural narrative, retrain the imagination, and remind us—in painfully beautiful sentences—that we are not alone, and not eternal.

As Margaret Atwood warned decades ago, “It’s not climate change—it’s everything change.” And literature, finally, changed with it.

The climate novel is not escapism. It is alarm, prayer, confession, and eulogy—all on the same page. In an age where the Earth itself has become unstable, the most radical act a writer can do is make us feel the ground shifting beneath our sentences.

The Rise of Autofiction, Memoir, and the Cult of the Self

“When the world grew unbelievable, the writer turned inward—for proof of existence.”

If the 21st century began with globalism, climate anxiety, and collapsing truths, by the mid-2010s, literature took an abrupt detour: inward. Facts were contested. Systems crumbled. Identities blurred. So writers did what they’ve always done when reality becomes unstable—they wrote themselves into the center.

This wasn’t traditional autobiography, nor was it the old novel dressed in confessional robes. It was autofiction—a slippery hybrid where fact and fiction flirt, quarrel, and never quite reconcile. And it wasn’t about plot. It was about presence. Voice became the story. The narrator became the landscape.

Autofiction: The Art of Looking in the Mirror (and Writing About the Mirror)

In autofiction, the line between author and character is not blurred—it is taunted. Think Karl Ove Knausgård, the Norwegian literary meteor who published a six-volume opus (My Struggle) that chronicled everything from brushing his teeth to his father’s death. It was called boring by some, brilliant by others, but undeniably radical in its naked banality. Knausgård didn’t just write himself—he documented himself as though he were both subject and specimen.

In the U.S., Ben Lerner mirrored this move with Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, where the narrator is a writer named Ben who talks about writing a novel that resembles the one we’re reading. It’s not meta-fiction. It’s meta-existence.

Autofiction is not an admission of ego. It is a literary diagnosis: the self is the only constant in a shifting world.

Memoir’s Resurgence: Trauma, Voice, and the Politics of Telling

Alongside autofiction rose memoir’s second golden age—but this time it was intersectional, political, and urgent.

Memoirs were no longer about celebrity, inspiration, or linear journeys. They became tools of survival, identity reclamation, and truth activism. Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House (2019) broke memoir open, telling a queer abusive relationship through fragmented forms—glossary, fairy tale, Choose-Your-Own-Adventure—because trauma defies chronology.

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019), while fictional, reads like a poetic letter-memoir—a Vietnamese-American queer boy writing to his illiterate mother, tracing identity through language, love, and loss. It’s autofiction, yes, but also ancestral record and survival song.

Memoir here is not memory. It’s meaning wrestled from chaos, one page at a time.

Who Owns the Story?

But autofiction and memoir raised a new anxiety: Who gets to write whom?

Is every story written from lived experience more valid? Does crafting a character from your life make it fiction—or an act of public self-exposure? Is it brave—or performative?

Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? (2010s) and Motherhood (2018) did not provide answers. Instead, they posed the questions as narrative. The page becomes a confessional booth—but the reader plays the priest.

In autofiction, writing replaces therapy, prayer, conversation, even identity itself.

Digital Culture and the Collapse of Privacy

One cannot separate this trend from its historical context: the rise of social media, selfies, online oversharing, and the simultaneous hunger for authenticity and performance. As Instagram perfected aesthetic self-curation, literature rebelled by being raw, awkward, unfiltered.

Authors were no longer just voices. They were brands. Twitter became a literary form. Substack newsletters blurred the line between diary and essay. Writers became influencers. Influencers became authors. And the novel became, at times, a long caption waiting for likes.

Autofiction, then, is not vanity. It is the last refuge of voice in a world that commodifies the self and monetizes attention.

Fiction as Performance Art

Some writers leaned into the performative nature of the self. Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick (1997, revived in the 2010s) became a feminist autofiction cult classic—turning obsession into ideology, confession into criticism. It was messy, brilliant, defiant—and prophetic of the online intimacy economy that followed.

Tao Lin, Kate Zambreno, and Elisa Gabbert all participated in this literary staging of self—not polished personas, but neurotic, fragmented selves unsure if they were being read or surveilled.

Autofiction, here, is not about clarity. It is about blurred outlines and the courage to appear unfinished.

The Gendered Self and Writing the Body

A parallel trend emerged in feminist body memoirs, where the body itself—its pain, pleasure, trauma—became the central text.

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) fused memoir, theory, queerness, and motherhood in a genre-defying blend that became a manifesto for fluidity—in gender, genre, and truth.

Roxane Gay’s Hunger (2017) chronicled trauma, body image, and vulnerability with devastating candor, resisting redemption arcs or fat-girl stereotypes. It was not empowerment porn. It was testimony.

These works redefined authorship as embodiment—writing not just from the mind, but from the scar, the womb, the rage, the craving.

In an age that demanded spectacle, the literary self did not perform. It bled, blurred, and quietly insisted: “This is me. This is fiction. This is truth. Choose your discomfort.”

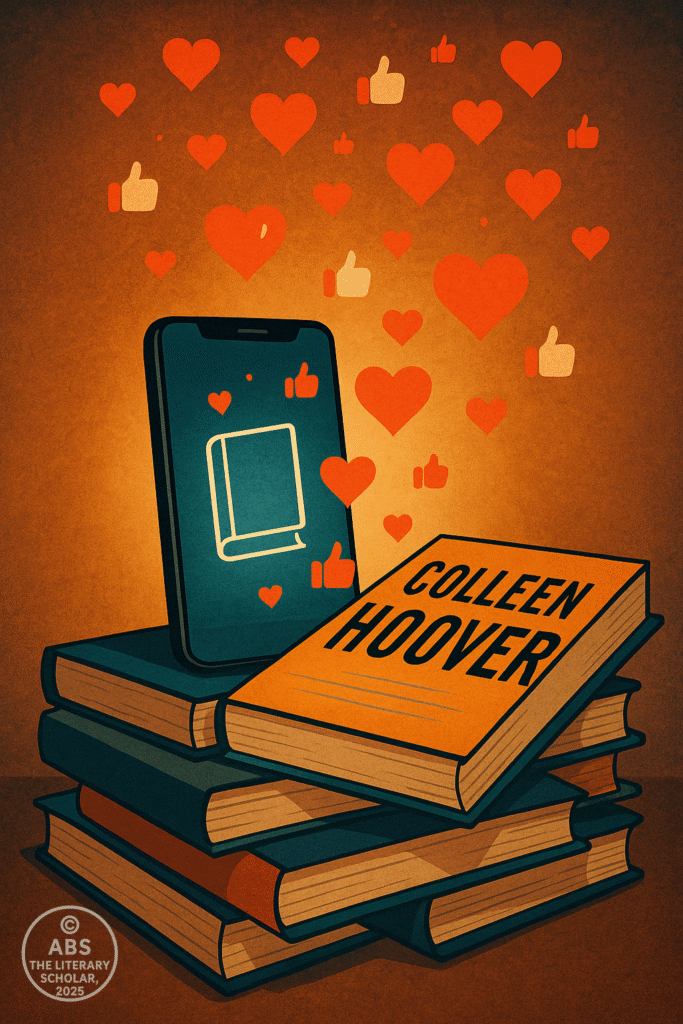

The BookTok Boom — When Literature Met the Algorithm

“The future literary critic is a girl with dyed hair holding a ring light.”

It began with a whisper—a tear-streaked recommendation on TikTok, a book waved in front of a trembling phone camera, a reader saying, “This destroyed me.” A few weeks later, that same book—obscure, out-of-print, or ignored by the establishment—was #1 on the New York Times bestseller list. Critics were puzzled. Publishers were thrilled. And BookTok was born.

This was not your grandmother’s book club. This was algorithmic literature: viral, emotive, unacademic, and deeply effective.

In a world where attention spans were collapsing, literature found new life on a platform built for dance trends and absurd comedy. The readers weren’t sipping espressos—they were screaming, crying, throwing up (in lowercase). And somehow, they were reading. In droves.

When Book Recommendations Went Viral

The logic was stunningly simple. TikTok’s algorithm didn’t care about credentials—it rewarded emotion.

Say “this book ruined me,” look broken, maybe sob a little, and boom—Colleen Hoover’s sales explode. A video about The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo leads to a 400% spike in sales. People aren’t just buying books—they’re joining emotional cults around them.

A few viral phrases now rule the kingdom:

“This book healed my inner child.”

“This couple had no business being this well written.”

“If you loved A Court of Thorns and Roses, read this next.”

The hashtags alone became literary ecosystems:

→ #BookTok, #SpicyReads, #SadGirlBooks, #EnemiesToLovers, #BookBoyfriend

Who Got Elevated, Who Got Erased

Colleen Hoover became the undisputed queen of BookTok. Her emotionally chaotic novels—It Ends with Us, Ugly Love—are frequently criticized for their prose but adored for their addictive angst. Literary purists sneer. TikTok replies with millions of sales.

Taylor Jenkins Reid, Ali Hazelwood, Emily Henry, and Madeline Miller (especially The Song of Achilles) all soared—books that blend accessible prose, deep feels, and often romantic despair.

But this literary economy isn’t fair.

→ Diverse, queer, and translated voices still struggle to trend.

→ TikTok often prefers white, heterosexual, cis love stories—with a hint of trauma and a heavy dose of lust.

This is not democratization. It’s gamification. And like all games, it has rules—and losers.

The Backlist Renaissance

BookTok didn’t just promote new releases. It exhumed the dead.

→ We Were Liars (E. Lockhart) returned nearly a decade after release.

→ Verity and It Ends With Us became instant classics… years after publication.

→ Even The Bell Jar trended—often accompanied by aesthetic montages of “sad girl fall.”

Suddenly, being out of print was not death. It was potential BookTok resurrection.

Publishers scrambled to reissue, redesign, and re-market like teenage influencers. Covers got sexier. Taglines got sadder. Descriptions got punchier. Everything had to be readable in 30 seconds of vertical video.

The Rise of the Author-Influencer

This era blurred the line between writer and performer.

Authors now market their own books in skits, thirst traps, and reaction videos. Some excel—others implode. The literary mystique is gone. In its place: authenticity as performance.

→ An author who posts aesthetic café shots and cries over reader reviews? Loved.

→ An author who refuses to play the game? Forgotten.

Traditional reviews lost clout. TikTok comments replaced blurbs. The readers became curators. The influencers became gatekeepers. And the publishers… simply watched, begged, and budgeted accordingly.

Criticism 2.0 — Crying on Camera as Literary Theory

BookTok criticism isn’t concerned with postmodernism or the Bildungsroman. It’s emotional. Personal. Unfiltered. And wildly contagious.

A typical review might be:

“This book made me question my entire existence.”

No star rating. No literary jargon.

Just a human, sobbing, recommending it like a love confession.

Is it rigorous? No.

Is it real? Yes.

Is it moving books? Absolutely.

Critics scoff. Bookstores smile.

Genre Wars: Romance, Fantasy, and Spice

BookTok has genre favorites.

Fantasy romance (Fourth Wing, From Blood and Ash) is a guaranteed hit.

“Spice” scale ratings (how many 🔥 emojis per scene) are crucial.

Dark academia, morally gray heroes, and trauma bonding are in.

Literary subtlety? Often ignored.

But buried within these tropes are genuinely compelling narratives, new literary communities, and a revival of fanfiction-like intimacy between reader and text.

This is not just reading. This is parasocial literature. Readers want not just a story—they want an emotional event.

BookTok didn’t kill literature. It gave it CPR—in a glittery hospital gown, holding a ring light. In a distracted, digital age, the most analog of arts went viral.

It might not be the canon we expected.

But it is the reading culture we now inhabit.

And for better or worse, it’s not quiet anymore.

Protest and Power — When Literature Spoke Back

“In times of silence, the sentence becomes a sword.”

The years following 2015 were not quiet. The world roared. In the streets. On screens. In systems cracking under the weight of injustice. And literature—no longer a passive observer—entered the fray with fists and fire.

Contemporary fiction became a battleground, where identity, race, gender, and state were interrogated, reimagined, and, sometimes, flatly refused. Writers across the globe wielded literature not just as art—but as protest. They weren’t asking questions anymore. They were delivering verdicts.

The Political Page: Fiction as Activism

Literature returned to the barricades. The idea that the personal is political? It became the narrative spine.

Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give (2017) was a cultural detonation. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, it gave voice to the fury of young Black Americans living under systemic threat. This was not abstract allegory. This was a novel that echoed with gunshots and grief, and yet still offered humanity, resilience, and hope.

Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half explored racial passing, identity slippage, and historical silence through twin sisters living divergent racial realities—one Black, one passing as white. A multigenerational story, but also a scalpel carving through racial constructs.

Tommy Orange’s There There (2018) shattered stereotypes with a fragmented chorus of Native American voices converging at a powwow—urban, angry, poetic, lost, and long overdue in mainstream fiction.

These were not just books. They were manifestos wrapped in metaphor.

The Global Chorus: Protest from the Margins

Outside the Anglophone West, literature spoke from burning frontlines:

-

In India, Meena Kandasamy’s When I Hit You offered a blistering account of marital abuse cloaked in the façade of intellectualism. It was a novel, yes—but also a feminist punch to patriarchal smugness.

-

In Nigeria, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie continued her sharp cultural interventions, both in essays and fiction. Dear Ijeawele and her TED-talk-turned-book We Should All Be Feminists became global feminist primers—quoted more in classrooms than critical theory.

-

In Egypt, Alaa Al Aswany‘s The Republic of False Truths dared to chronicle the bloody repression of the Arab Spring—a novel banned in its own homeland, smuggled out like contraband truth.

The trend was unmistakable: The more oppressive the regime, the more urgent the fiction.

Poetry, Too, Went to War

Don’t let the line breaks fool you. Poetry returned to its primal function: rage, remembrance, and resistance.

→ Amanda Gorman, the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history, reminded a fractured nation that “the hill we climb” still stands—if not with ease, then with literary courage.

→ Danez Smith, Warsan Shire, and Claudia Rankine gave us lyricism soaked in blood and bias. Their works did not soothe. They named the wound and left it raw.

→ Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem (2020) was not just about romance—it was about land, language, loss, and erotic defiance in a colonized body.

Contemporary Literature 2013–2025 : Fiction and the Feminist Fury

Feminist fiction in this era did not whisper about gender—it growled, bled, and burned.

-

Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other (2019) carved out twelve lives of Black British women and nonbinary characters, dismantling gender binaries and Eurocentric literatures in one Booker-winning sweep.

-

Elena Ferrante, though published earlier, reached a global crescendo with the Neapolitan Novels, revealing female rage, friendship, ambition, and betrayal in ways the canon had never permitted.

-

And then there was Margaret Atwood—returning with The Testaments (2019), the sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, a book that found new life in red cloaks at protest marches around the world.

Fiction became the banner women carried, not just what they read.

The Essay as Explosion

Alongside fiction, personal-political essays returned with raw urgency.

→ Roxane Gay, Rebecca Solnit, Mikki Kendall, Jia Tolentino, and Hanif Abdurraqib all published works that blended memoir, critique, and manifesto. These weren’t just “think pieces.” They were survival texts for the intellectually exhausted.

The essay became the instant-response genre of the digital age—faster than novels, deeper than tweets, and far more permanent than trending hashtags.

Protest in Form, Not Just Theme

Many writers went further—rebelling not just in content, but in structure.

→ Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas responds directly to the U.S. government’s apology to Native Americans—using language as legal rebellion.

→ Claudia Rankine‘s Citizen: An American Lyric blended poetry, photography, and criticism into a hybrid form that defied classification—mirroring the racial limbo of its subject.

Form became message. The refusal to conform became a form of protest in itself.

Literature That Won’t Sit Still

This was the literature of knees on necks, borders in flames, and women’s bodies written in legal codes.

And so the writers wrote back. Not to comfort. Not to entertain. But to dismantle.

In this era, reading is no longer neutral. It’s an act of witnessing. Sometimes of complicity. Sometimes of solidarity. But always of engagement.

As one author put it:

“If you’re comfortable while reading this, you’re not reading closely enough.”

Global Voices — Translation, Transgression, and the World on the Page

“The future of literature is multilingual, multi-shelved, and magnificently unbothered by borders.”

If the 20th century was obsessed with the idea of the “Great American Novel,” the 21st quietly burnt that passport. We now live in a world where literature no longer asks for a visa. It simply translates itself.

In the post-2010 literary world, global fiction was not a side shelf—it was the main event. For the first time in history, translated literature began to sell, circulate, and win with the same pomp once reserved for white, English-language authors writing from New York or London. And this shift was not just geographical—it was aesthetic, linguistic, and political.

Translation as Creation, Not Approximation

Gone are the days when translation was treated like a necessary inconvenience. The new literary movement treats translation as co-authorship.

Jennifer Croft (translator of Olga Tokarczuk) and Anton Hur (Korean to English translator of Sang Young Park and others) became literary celebrities in their own right.

Translators now appear on book covers. They win awards, do festivals, and get reviewed alongside authors.

In many cases, the rhythm and style of a book are co-constructed, not merely passed along.

In the words of one reviewer:

“The translator is the second heartbeat of the novel.”

Korean Fiction’s Quiet Global Takeover

The ascent of Korean fiction is no longer a trend. It is a wave.

Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (trans. Deborah Smith) brought raw bodily rebellion to global consciousness.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo became the feminist battle cry of a generation, dissecting workplace sexism, silent mothers, and generational trauma with ice-cold clarity.

Writers like Sang Young Park (Love in the Big City) and Hwang Sok-yong brought queerness, protest, and postwar pain to the page—with humour, sex, and rage in equal measure.

Latin American Fiction: Magical, Political, Undeniably Contemporary

While Gabriel García Márquez once defined the region’s global image, 21st-century Latin American literature broke away from magical realism and delivered something rawer, riskier.

Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream (Argentina) blurred eco-horror and maternal anxiety into a psychological, poetic scream.

Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive fused road novel, border crisis, and found audio into a genre-defying masterpiece of immigrant despair.

Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season was so violent, so visceral, it felt like being flayed by language itself.

These novels didn’t seek to represent nations. They captured hauntings, injustices, and the ghosts of dictators and mothers alike.

Arabic and Persian Voices: Poetic Resistance

From countries where speaking too loudly could mean exile—or death—emerged some of the most powerful fiction of the decade.

Shokoofeh Azar’s The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree offered an Iranian tale of political execution, spiritual transformation, and memory told in luminous, lyrical whirlpools.

Jokha Alharthi, the first Arabic-language woman to win the Man Booker International Prize, gave us Celestial Bodies—a quiet but seismic novel on love, slavery, and modernity in Oman.

Hoda Barakat‘s The Night Mail stitched together voices of the displaced in letters never sent—dislocated, disoriented, devastating.

These were not simply novels. They were confessions from beneath censorship, prayers dressed as stories.

Africa’s Literary Renaissance: Bold, Brave, Beautifully Bilingual

Forget the “single story.” The continent has never been more plural.

Chigozie Obioma, called “the heir to Chinua Achebe,” wrote An Orchestra of Minorities—a tragic Igbo epic narrated by a guardian spirit.

Mbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers and How Beautiful We Were tackled colonial capitalism and environmental destruction with elegiac fury.

Leila Aboulela, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi infused oral traditions, gender questions, and multilingual narrative into every page.

African literature no longer “arrives” in translation. It walks in like royalty—already home.

The Booker International and Other Border-Crashing Awards

The Man Booker International Prize became the unofficial Olympics of world literature:

Olga Tokarczuk (Poland) with Flights and Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead made metaphysical wanderlust thrilling.

David Diop’s At Night All Blood Is Black gave World War I a Francophone-African perspective so brutal it read like violence braided into myth.

Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell, shocked the Western market with its surreal feminism, breaking both language and gender norms.

Meanwhile, Tilted Axis, Charco Press, And Other Stories, and Archipelago Books built publishing houses that were more like embassies for the literary stateless.

The Hybrid, The Experimental, The Untranslatable

Some voices refused easy categories.

Yōko Tawada wrote The Emissary in Japanese about post-apocalyptic Japan, but with no kanji, only kana—a radical linguistic constraint.

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s The Discomfort of Evening won the International Booker with prose that made trauma disturbingly sensual.

Sayaka Murata, in Convenience Store Woman, broke social taboos on gender, neurodivergence, and work culture—with the eerie calm of a retail robot.

These were books that laughed at your desire to “relate”. You didn’t enter them. They entered you.

The Literature of Elsewhere Is Already Here

Global literature is no longer a box in a corner bookstore labeled “World.” It is the world.

The borders have blurred. The translators are stars. The languages sing across platforms.

And the reader? They no longer care where a story is from—only what truth it dares to tell.

In the 21st century, the most radical literature doesn’t ask to be understood.

It simply says:

“Read me. And then try to remain the same.”

Memoir, Autofiction, and the Rise of the Fractured Self

“The story of ‘me’ has never been messier—and never more real.”

Once upon a literary time, fiction and nonfiction lived on opposite shelves. The former spun worlds. The latter reported them. But in the 21st century, that wall has crumbled like an unreliable alibi.

Today, we inhabit the era of autofiction—that fascinating, messy hybrid where the writer becomes the protagonist, where memory and imagination tangle in deliberate discomfort. It is not memoir, yet not quite fiction. It is “based on a true story” with a wink and a cigarette.

Why the surge? Because readers no longer trust neat narratives. The world is fractured. Identities are fluid. Trauma leaks. And in such an era, the most honest literature often wears a mask with the author’s own face.

Autofiction: Me, Myself, and a Very Public Breakdown

Karl Ove Knausgård didn’t just break literary convention with My Struggle. He smashed it with six volumes of minute-by-minute recollection, covering everything from his father’s death to his baby’s diaper change. Was it art? Narcissism? Both? Either way, it sold millions—and proved that the mundane can be mythic when stripped of pretense.

Rachel Cusk followed with her razor-sharp Outline trilogy. Here, the narrator barely speaks—but everyone else does, spilling intimate confessions as if the mere presence of a quiet woman could trigger collapse. Cusk redefined character by erasing it.

Then came Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?—part script, part memoir, part novel, all chaos. It asked, not rhetorically, what it means to perform yourself on the page.

In autofiction, truth is not a destination. It is a performance art.

Memoir: Confession as Cultural Commentary

If autofiction blurred lines, memoir blew open floodgates. No longer confined to celebrities and politicians, memoirs became a collective therapy session disguised as literature.

Tara Westover’s Educated stunned readers with her Mormon survivalist upbringing and her rise from isolation to Cambridge PhD. It wasn’t just a memoir. It was a Bildungsroman soaked in blood and books.

Carmen Maria Machado‘s In the Dream House turned domestic abuse into a postmodern haunted house—queer, literary, and structurally uncontainable. Each chapter uses a different genre: Gothic, legal case, choose-your-own-adventure.

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts—part memoir, part theory, part lyrical outburst—explored queer family-making, desire, and fluid identity with an intimacy that felt like eavesdropping on a brain and a body mid-conversation.

These weren’t just stories of survival. They were how literature survived the collapse of certainty.

The Rise of the Vulnerable Intellectual

In a world where facts lie and news scrolls lie faster, the new authority figure in literature is not the omniscient narrator, but the wounded thinker.

→ Ocean Vuong, in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, wrote a letter from a queer Vietnamese-American son to his illiterate mother—a novel that read like a memoir disguised as a poem. Lines bled. Time folded. Gender blurred.

→ Durga Chew-Bose, Emily Ratajkowski, Roxane Gay, Leslie Jamison—these essayists and memoirists didn’t just share. They philosophized through pain. They used vulnerability as epistemology.

The new literary power isn’t knowing more than the reader. It’s being just as confused, but saying it better.

Hybrid Forms, Fractured Frames

The rise of self-referential, fragmented, and experimental storytelling mirrored a world suffering from attention collapse and identity overload.

Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation and Weather used aphorism, collage, and clipped inner monologue to simulate the distracted mind of a modern woman with too much to hold.

Joan Didion, the queen of literary detachment, remained a looming presence even posthumously—her crisp sentences still defining grief, memory, and American contradiction.

Ben Lerner, with Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, turned the privileged white male gaze back on itself—neurotic, self-conscious, and semi-lovable in its relentless meta-awareness.

Literature was no longer about plot. It was about perception.

About being—not being interesting.

The Ethics of Exposure: Who Owns the Story?

With great self-exposure came great controversy.

What if your autofiction reveals other people’s truths?

What if your memoir is more fiction than memory?

What if your trauma becomes your brand?

Authorial responsibility became the new literary landmine.

Some called it brave. Others called it emotional pornography. But the best works never settled for confession. They transformed pain into structure, memory into metaphor, self into narrative engine.

The Age of ‘I’ Without Apology

This is the age of the fragmented self.

The confessional as critique.

The messy as meaning.

We no longer trust third-person omniscience. We don’t want flawless heroes.

We want narrators who bleed, glitch, ramble, contradict, and ask, like us:

“How should a person be?”

In that question, asked again and again in books, lies the defining pulse of this era’s literature.

Literary Techscapes — Digital, AI, and the Post-Book World

“When books stopped ending at the last page—and began rewiring the medium itself.”

Once upon a literary age, a book was a book: pages, chapters, an author, a reader, and the quiet intimacy of paper. But in the age of screens, scrolls, and servers, literature has leapt off the page. It is being written in code, fed through algorithms, tweeted into brevity, or voiced by machines. And somewhere amidst the chaos, it is also being rediscovered in entirely new ways.

This is not a eulogy for the novel. It is an evolution diary—an account of how storytelling has adapted to survive the digital flood and remain culturally potent.

1. Instagram Poets and the Rise of Scroll-Sized Emotion

Call it Insta-poetry, pop-lit, or quote-porn—but don’t call it irrelevant. The rise of poets like:

Rupi Kaur (Milk and Honey),

Nikita Gill (Fierce Fairytales),

Yrsa Daley-Ward (Bone)

marked a shift in who gets to write, publish, and be heard.

These writers bypassed traditional gatekeepers and carved their empires out of typography, heartbreak, and hashtags. Their short, minimalist verses were not accidental—they were built for swiping, for saving, for screenshotting.

Critics scoffed. Audiences roared.

Literature had entered the algorithmic bloodstream.

2. The Tweet, the Thread, and the Viral Micro-Story

In a world of 280 characters, storytelling learned to condense, tease, and explode in fragments.

Teju Cole’s Small Fates project on Twitter blurred the line between journalism, fiction, and moral meditation—often telling entire lives in a single tweet.

Experimental flash-fiction challenges on platforms like Twitter and Reddit gave rise to a new kind of literary form—immediate, interactive, and utterly democratic.

Brandon Taylor, author of Real Life, often uses his Twitter feed as a literary workshop—crafting parasocial critiques, aphoristic insights, and poetic micro-monologues that outshine many published essays.

3. Hypertext Fiction and the Immersive Reading Experience

The Choose Your Own Adventure format, once relegated to children’s books, has reemerged—this time with philosophical, metafictional, and postmodern intensity.

Twine, an open-source storytelling platform, empowered writers to build nonlinear, interactive fictions where readers navigate not just plot but identity, gender, and memory.

Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s surreal interactive narratives redefined what it meant to “read” a game.Bandersnatch (part of Black Mirror) made interactive fiction a mainstream Netflix event—a literary premise with a tech twist.

Hybrid works like Samantha Gorman’s Pry—half novel, half touch-based iPad experience—explored PTSD and memory collapse through swipes, pinches, and sound.

Reading was no longer passive. It became a tactile, digital ritual.

4. Audiobooks and the Return of the Oral Tradition

In a plot twist worthy of the ancients, storytelling returned to the mouth and ear.

The audiobook industry exploded post-2015. Writers now write with audio rhythm in mind.

Daisy Jones & The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid was structured as an oral history—perfect for full-cast audio drama.Publishers like Libro.fm and Audm emphasized voice-led nonfiction. The spoken word became a legitimate literary form again, not just an accessibility feature.

Podcasts like LeVar Burton Reads or The New Yorker Fiction Podcast created literary salons of the ear—curated, intimate, and global.

Literature returned to the oral, just as we plugged it into our pockets.

5. AI, Machine Writing, and the Rise of the Synthetic Scribe

Somewhere between sci-fi and satire, AI is now writing fiction. And it’s… surprisingly coherent.

Sudowrite, ChatGPT, and Narrative Device platforms allow writers to co-compose with machines—sometimes to cure writer’s block, other times to collaborate with the uncanny.

In 2022, the first AI-authored short story made it into a literary magazine. The editor knew… and published it anyway.

Kazuo Ishiguro, in Klara and the Sun, did not just imagine AI consciousness—he mirrored it back at readers, asking whether empathy could be programmed.

The philosophical question is no longer “can a machine write?”

But rather: what kind of soul does literature need, if any?

6. Ebooks, Digital Piracy, and the Ethics of Access

The digital era has democratized and destabilized literary access.

While ebooks outsold print during pandemic years, platforms like Z-Library and Libgen exploded, leading to global debates on the ethics of free access versus author livelihood.

Authors like Rebecca Solnit and Neil Gaiman acknowledged the paradox: free books build readers, but destroy economies.

Subscription platforms like Scribd and Kobo Plus became the Spotify of books, but with the same ethical fog: How does a writer survive when stories become streams?

Literature isn’t dying. It’s being diluted, distilled, and downloaded.

7. AI as Character, Creator, and Critic

It’s not just that AI writes. It now lives in fiction, increasingly as metaphor and menace.

The Every by Dave Eggers imagines a world where tech companies morph into governments and privacy becomes fiction.

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Chain-Gang All-Stars fuses reality TV, social media, and AI-driven prison labor—a capitalist dystopia built with literary fire.

The Employees by Olga Ravn, shortlisted for the International Booker, gives us a spaceship filled with human and synthetic workers, slowly unraveling in poetic fragments.

It’s part sci-fi, part office satire, part existential fable.

AI is no longer a tool. It’s a theme, a plot twist, a warning.

8. Literature in the Platform Economy

Writers are now also content creators.

Substack newsletters became the new independent press: George Saunders, Roxane Gay, Patti Smith, and Hanif Abdurraqib deliver literature directly to inboxes.

TikTok’s BookTok transformed publishing—making The Song of Achilles, It Ends With Us, and A Court of Thorns and Roses global bestsellers years after publication.

NFT-based novels, interactive metaverse storytelling, and blockchain publishing are emerging—not for quality, but for economic autonomy.

We’re watching literature leave the bookshelf… and enter the stock market.

When Literature Stops Being a Thing and Becomes an Atmosphere

The novel is not dead. It’s just started to glow, glitch, and whisper through other mediums.

Today, literature is not only what you read.

It is what you listen to, swipe past, echo in, train with, game through, and dream beside.

And whether it’s typed by a human, whispered by a bot, or scrawled on a napkin between apps—

if it moves you, if it thinks you, it still counts.

Welcome to the age of literary osmosis.

You don’t just read it anymore.

You live inside its code.

Grief Scripts — Writing Loss, Trauma, and the Inner Rupture

“When literature became not just a mirror to suffering, but a ritual of survival.”

There are literary periods defined by triumph. Others by transcendence. But the years since 2020 have asked literature to do something far more difficult — to sit with pain, to name it, to stay. This is not merely confessional writing or trauma porn. It is something richer, deeper, and more emotionally intelligent. It is what happens when the inner wound becomes the narrative center, and form itself begins to fray under the weight of human vulnerability.

In this section, we explore how contemporary writers have transformed grief into grammar, breakdown into structure, and personal loss into communal reckoning. There are no neat resolutions here. Only raw pages — bloodied, blistered, and brave.

1. The Memoir as Mourning Ritual

In the last decade, memoirs of loss have become literary phenomena, not because of sensationalism, but because they articulate the unspeakable with radical honesty.

Joan Didion’s Blue Nights and The Year of Magical Thinking remain seminal texts in understanding the literary processing of grief — sparse, elegant, devastating.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Notes on Grief (2021), written after the death of her father, is a masterclass in restrained sorrow. It captures the peculiar dislocation of diasporic mourning: “Grief is a cruel kind of education.”

Catherine Newman’s We All Want Impossible Things (2022) balances humor and despair, chronicling terminal illness without sentimentality. Grief, here, laughs through its tears.

The memoir is no longer autobiography. It has become collective elegy.

2. Fictional Forms of Inner Collapse

While non-fiction held up mirrors, fiction walked through the wreckage.

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (2015) became infamous for its unflinching portrayal of trauma, abuse, and chronic emotional pain. Critics debated its brutality; readers clung to it like a lifeline.

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019) blurred genres — letter, poem, novel — to narrate the intergenerational transmission of trauma, sexuality, war, and silence.

Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House used experimental structures — choose-your-own-adventure, film script, fairy tale — to deconstruct abuse in queer relationships, giving voice to a historically erased experience.

These novels do not soothe. They surge, unraveling the literary contract in order to remain emotionally faithful.

3. Grief and Pandemic Literature: Writing Through Lockdown

The global trauma of COVID-19 found expression not just in headlines, but in quiet, aching prose.

Sarah Moss’s The Fell (2021) is a stream-of-consciousness lockdown novel that captures the paranoia, claustrophobia, and ambient dread of isolation. The virus is not just a backdrop—it’s an atmospheric character.

Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet (Autumn, Winter, Spring, Summer) was literature’s real-time response to Brexit, the pandemic, and the erosion of public trust. Her voice is elliptical, witty, and sharp as ever—anchoring the chaos in myth and music.

Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song (Booker Prize, 2023) — though dystopian — reads like a pandemic fever dream. It is about surveillance, collapse, and the erasure of normal life. The trauma is ambient, bureaucratic, and brutally quiet.

These books didn’t try to interpret catastrophe.

They simply held it.

4. Death, Elegy, and the Rewriting of the Personal

Contemporary elegiac writing doesn’t romanticize death. It decentralizes it—allowing the mourning process to include rage, absurdity, detachment, and even creativity.

Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers (2015) fused prose, poetry, myth, and nonsense to depict a father and two sons mourning their mother, with a talking crow as their guide.

Han Kang’s The White Book (translated by Deborah Smith) uses meditations on white objects — snow, bones, paper — to mourn a sibling never born. Grief becomes visual, elemental, unspeakable.

Naja Marie Aidt’s When Death Takes Something From You Give It Back is a haunting, fragmented memoir of losing a son, where syntax itself shatters under emotional weight.

Grief has fractured form.

And form, in turn, has adapted to express what cannot be fully known, only felt.

5. Collective Grief and the Poetics of Protest

Modern grief is not only private. It is political.

Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas uses poetic form to critique government apologies to Native American communities. Grief here is historical, inscribed in treaties and language distortion.

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric navigates racial trauma through prose-poetry — microaggressions, erasures, and the weight of accumulated injustice.

Warsan Shire, the Somali-British poet whose lines Beyoncé sampled in Lemonade, writes with molten grief — refugee trauma, womanhood, exile, and the ache of origin:

“No one leaves home unless / home is the mouth of a shark.”

These writers turn sorrow into resistance.

Loss becomes literature. Literature becomes warning.

6. The Ethics of Reading Pain

A question haunts this entire movement:

What does it mean to consume trauma as narrative?

Do readers come to grief-lit for catharsis, voyeurism, or solidarity?

Contemporary authors increasingly interrogate this:

Jenny Offill, in Weather, exposes climate grief, social fatigue, and micro-doom with ironic restraint.

Rachel Cusk’s Outline Trilogy avoids the “authentic voice” entirely—its narrator listens, absorbs, disappears. Is this silence a trauma response? Or a new mode of literary attention?

Modern literature does not resolve the paradox.

It merely refuses to simplify pain into plot.

Literature as Psychological Cartography

In this era, books are not maps of the world.

They are maps of what the world did to the psyche.

We no longer read only for plot or pleasure. We read to see if someone else has felt what we are ashamed to say aloud. And when a page echoes our private tremors — we know:

We are not alone.

This is not just the literature of grief.

It is the grief that became literature.

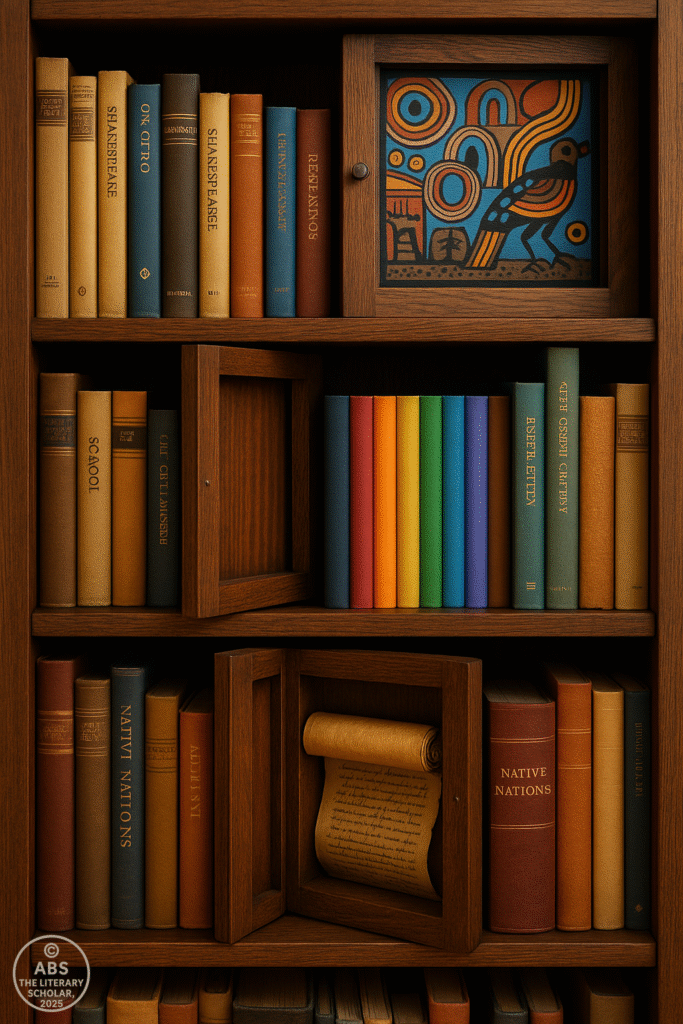

Canon in Motion — The Unfinished Shelf of Contemporary Literature

“The canon is no longer carved in marble. It is edited in real time.”

Once upon a time, the literary canon was a museum of agreed greatness, its curators mostly white, male, and sure of their choices. Writers were either inside the hall of fame or looking in through the frosted window. But the 21st century, especially the post-2012 decade, has upended that static model.

We now live in a time where the canon is contested, curated by communities, algorithmically nudged, socially debated, and re-written every syllabus season. The question is no longer “What is great literature?” but “For whom, when, and why?”

1. Goodbye to Gatekeeping: Democratization by Disruption

The explosion of independent publishers, online literary journals, social media platforms, and global book communities has decentralized literary power.

The BookTok phenomenon has made Colleen Hoover outsell nearly everyone in the English-speaking world. Critics scoff. Readers don’t care. The market is no longer canon’s ally—it’s its unpredictable twin.

Small presses like Fitzcarraldo Editions, Graywolf, and Tilted Axis have become curators of contemporary genius, publishing writers like Olga Tokarczuk, Valeria Luiselli, and Bhanu Kapil before the world caught on.

Literary prizes—once slow to adapt—are now actively widening the lens. Recent Booker lists have included diasporic narratives, genre fiction, experimental works, and authors writing across languages and geographies.

Canon, meet chaos.

Or rather, meet curated pluralism.

2. Curriculum Revolutions: What Students Are Reading Now

In universities and classrooms across the world, students are increasingly reading “literature as a conversation”—across centuries, identities, and geographies.

→ Toni Morrison taught next to Euripides.

→ Claudia Rankine next to T.S. Eliot.

→ Kindred and The Handmaid’s Tale have replaced The Scarlet Letter in more than one American syllabus.

It’s not that the classics are cancelled. It’s that they are being recontextualized, reframed, and interrogated.

And perhaps, rightly so.

For a canon that does not speak to now is merely a fossil.

3. The Fluid Shelf: A Living Canon in Progress

What makes a work “canonical” today? Enduring form? Influence? Social virality? Or some elusive aesthetic grip?

→ Kazuo Ishiguro writes speculative fiction about artificial beings (Klara and the Sun) and wins the Nobel.

→ Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels have entered mainstream literary curricula despite anonymity and translation.

→ Roxane Gay, Rebecca Solnit, and Jia Tolentino write essays that are both cultural artifacts and feminist manifestos.

The canon now includes:

→ Experimental nonfiction

→ Memoir-hybrids

→ Climate fiction

→ Queer romance

→ Graphic novels

→ Literary horror

→ Audiobook-exclusive narratives

The form is secondary.

What matters is emotional intelligence, thematic depth, and a literary voice that pierces the noise.

4. Canon as Resistance: Who Was Left Out — and Why

The contemporary canon is not just a celebration of inclusion. It is a recovery project.

→ Dalit, Black, Indigenous, queer, and non-Western writers are being published not as tokens, but as literary voices of historical omission.

Bama Faustina, Mahasweta Devi, Ocean Vuong, Saidiya Hartman, Avni Doshi, Leila Aboulela, Maaza Mengiste—their presence reorients the literary telescope.

Testimonios, oral narratives, letters, and poetic prose from the margins are now seen as literature, not anthropology.

The canon is expanding not by consensus but by courage.

By discomfort.

By argument.

And that is its greatest strength.

5. Archives of the Now: Literature That Documents Itself

One feature of the new canon is its self-awareness.

Today’s literature often acknowledges its place in history even while being written:

Zadie Smith, in Intimations, reflects on pandemic life with literary poise and quiet anger.

Teju Cole, in his essays, blends photography, memory, and cultural critique—literature as collage.

Claudia Rankine’s work continues to expose the uneasy intimacy between the poetic and the political.

In this way, contemporary literature curates itself—it is both artifact and artist.

6. Canonical Anxiety: The Fear of Forgetting Everything

But this flux isn’t easy. Many readers, teachers, and institutions feel disoriented by this endless expansion. If everything is literature, what is sacred? If every voice matters, how do we choose what to teach?

Yet perhaps that anxiety is itself a sign of growth.

A canon is not supposed to be comfortable.

It is supposed to reflect the soul of a time.

And right now, that soul is fragmented, hopeful, angry, diverse, reflective, and still unfolding.

An Unfinished Bookshelf

Contemporary literature has reclaimed the right to be unfinished.

It lives in podcasts and performances, in reels and reviews, in newsletters and marginalia, in hypertext and heartbreak. The writer is no longer waiting to be canonized. The reader is no longer looking for a Great Book. Instead, both are asking:

“What speaks to me now?”

And that, perhaps, is the real canon of the 21st century:

A shelf that changes shape depending on who’s reading.

The Canon Isn’t Dead — It Just Logged In

Once, to study literature was to trace a straight line—from Homer to Shakespeare, from Austen to Eliot. Today, it’s more like mapping a galaxy of live wires: autofictional sparks, TikTok-lit surges, climate cries, diaspora whispers, and genre rebellions.

What this contemporary era offers is not closure but curiosity. Not conclusions but collisions. The post-2013 literary moment is not a room with a view—it’s a house with expanding walls, where each voice cracks open a new window.

As professors, we no longer ask, “What book changed the world?”

We now ask:

“What world does this book change for you?”

And that’s where this scroll leaves off—not with a period, but with an ellipsis…

Because the bookshelf is still being built.

And the next chapter, quite literally, is being written as you read this.

Signed,

The Literary Professor

Where books are read not just for meaning, but for survival.

Where metaphors drown, and the flood is real.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance