Postmodern British literature : From Literary Labyrinths to Culture Jams — The Era of Digital Doubt, Cultural Mashups, and Narratives That Know You’re Watching

From The Professor's Desk

If the first wave of Postmodern literature looked inward — questioning truth, authorship, and narrative itself — the second wave turned outward, holding a cracked mirror to the world of TV anchors, global politics, collapsing ideologies, and viral media before virality had a platform. Welcome to the 1980s and 1990s, when the postmodern literature became pop culture. Irony wasn’t a literary tool anymore — it was the dominant tone of the age. Globalization, digitization, postcolonial unrest, and poststructural saturation collided in novels that no longer bothered pretending to be innocent. They layered irony over sincerity, voice over voice, and rewrote history from the margins. This was the era of hypertexts, media-saturated minds, and narratives stitched together from fragments, footnotes, and photocopies. Literature became a mixtape: of cultures, genres, philosophies, platforms. Writers didn’t just question reality — they questioned whether the question still mattered. Here, British fiction moved from metafictional experiments to transcultural storytelling, from fractured identity to digitally fragmented consciousness. The author hadn’t just died — they’d been uploaded, pirated, and remixed. The reader wasn’t just decoding a text — they were now scrolling through selves.

Postmodernism Literature Becomes Pop — Irony as Culture, Not Rebellion

Once upon a time, irony was a weapon. In the first wave of postmodernism, it existed to undermine authority, question narrative, and laugh in the face of high seriousness. But by the 1980s, irony had moved from the literature section to the front window of every high street shop. It wasn’t rebellion anymore. It was branding.

This was the moment when postmodernism became pop culture — not because it sold out, but because the world around it changed. Literature found itself surrounded by TV jingles, tabloid sensationalism, fast food slogans, political spin, and early internet static. The language of everyday life had become ironic, self-referential, and aggressively performative. And so, literature — always quick to adapt — shifted gears.

What emerged was a new kind of postmodern voice: detached but performative, cynical but hyper-articulate, angry but too ironic to admit it. British writers began to craft characters who were not just aware of the absurdity of their world — they were often obsessed with it. The line between the narrator and the stand-up comic grew thinner. Every observation came with a punchline. Every emotion came with a mask.

Enter Martin Amis, the literary equivalent of a sardonic grin. In London Fields (1989), Amis gives us a narrator who knows he’s a narrator, a murder mystery that refuses to play fair, and characters so vile they loop back around to being fascinating. It is a novel drenched in toxic masculinity, apocalyptic dread, and nihilistic wit, where love, literature, and even death feel like overused metaphors. But beneath the linguistic swagger and jaded voice lies something darker: a desperate search for meaning in a culture that consumes itself faster than it can reflect on anything.

Amis’s prose is deliberately excessive — lyrical and grotesque, poetic and profane. He doesn’t just describe modern life; he dissects it, flays it, and then laughs at its guts. His narrators are always a little smug, a little broken, and fully aware that they’re part of the same machinery they mock. And so, irony becomes not an act of critique, but a coping mechanism — the only way to speak honestly in a dishonest world.

A few years later, Will Self cranked the volume up even higher. His novels and short stories, like My Idea of Fun (1993), plunge the reader into warped minds, grotesque urban hellscapes, and linguistic fever dreams. Self’s protagonists are addicts, sociopaths, and corporate misfits — not because he wants to shock, but because madness and absurdity have become the most accurate lenses through which to view contemporary reality. His narratives blend psychiatric reports with satire, bodily fluids with existential dread, and the result is literature that feels like a drug-fuelled diagnosis of late capitalism.

What links these writers is their use of irony not as subversion, but as condition. Their characters do not rebel against the world — they’ve already accepted its absurdity. They survive it through language games, meta-commentary, and emotional detachment. Where the modernist narrator might break down and the postmodern narrator might vanish, these figures stay onstage, smirking through the apocalypse.

The tone is often performative. Narrators speak directly to the reader. Footnotes interrupt the story to offer contradictory facts. The novel becomes a stand-up act with philosophical baggage. But the audience is complicit — because we too live in a world where every statement is followed by a shrug, every truth qualified by quotation marks.

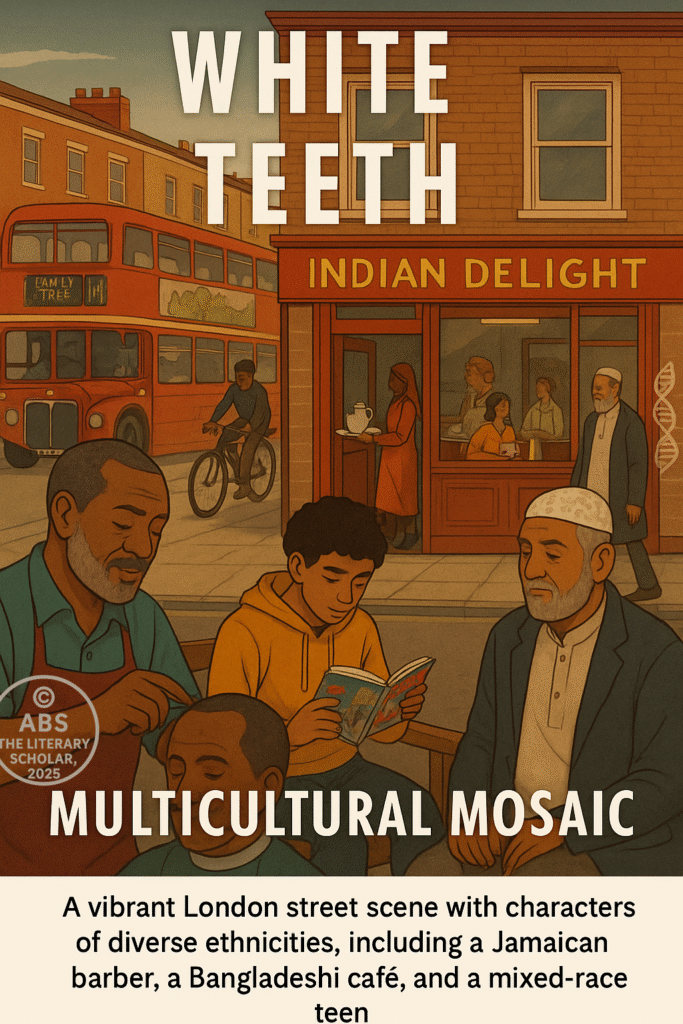

And it wasn’t just male writers playing the irony game. Zadie Smith, in her debut White Teeth (2000), enters the literary scene with a style that’s sharp, witty, self-aware — and deeply engaged with the fabric of multicultural, media-saturated London. Smith’s characters are constantly absorbing and remixing their surroundings: television, family mythologies, science, religion, genetics, colonial guilt, and kebab-shop philosophy. The novel is both wildly funny and intellectually bristling. It’s a reminder that postmodernism had become not just a literary style, but the operating system of contemporary consciousness.

In this new age, irony is not optional. It is the native tongue of the late 20th-century narrator. You can’t talk about love, death, or politics without also talking about how language itself has become suspect. You can’t describe a character without also referencing the tropes you’re trying to avoid. You can’t tell a story without apologizing for telling a story.

Even sincerity, when it appears, is in quotation marks. Feelings are real, but they’re filtered through pop references and media analogies. A character mourns not with a monologue, but with an Elvis song. A breakup is described through cinematic flashbacks. A childhood memory feels real only when it resembles an advert. Postmodern literature doesn’t reject emotion — it renders emotion through the culture that trained us to narrate ourselves.

By the end of the 1990s, irony had become the air fiction breathed. The narrator was no longer God or ghost — they were your deadpan flatmate who read too much Derrida and now comments on everything. But beneath the slick prose and bitter wit, the best of these novels still offer something vulnerable. They expose the aching need for meaning, even as they laugh at the concept.

Irony, in its second-wave postmodern form, is not a cheap laugh — it’s a kind of literary trauma response. When history collapses into spectacle, when politics becomes a media campaign, when identity becomes branding, then fiction must adapt. And it did. With dark humour. With meta-awareness. With characters who can’t stop talking — because silence, in a world of noise, feels like surrender.

As we move into the next section, we’ll see how postcolonial literature collides with postmodern techniques, producing stories that are not only ironic but hybrid, mythic, multilingual, and gloriously unstable. The Empire may have struck back — but literature, as always, was ready with footnotes, flashbacks, and a quietly devastating punchline.

Postcolonial Meets Postmodern — Telling Back The Empire, Ironically

When the Empire collapsed, it didn’t go quietly. It left behind shipping containers full of guilt, railway timetables, and English departments. And it left literature with an impossible question: How do you write back to a language that colonized your past, published your silence, and still expects footnotes when you speak? Postmodernism, with its playful mistrust of truth, history, and grand narratives, offered a surprising toolkit. It turns out that irony, fragmentation, and narrative rebellion aren’t just useful for white experimental novelists — they’re perfect for postcolonial fiction trying to unpick the neat stories left behind by colonial rule.

In Britain, the 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of novelists whose identities were shaped by dislocation, migration, memory, and myth. Their works weren’t just multicultural—they were multigenre, multilingual, and multi-everything. And crucially, they began to adopt postmodern forms not to sound clever, but to reflect the chaos and contradiction of inherited history. In their hands, the postmodern novel was no longer an abstract aesthetic game — it became a tool of reclamation, defiance, and artistic mischief.

No one wielded this tool more spectacularly than Salman Rushdie, whose The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995) reads like a magical realist fever dream drenched in political satire, mythic allusion, and fragmented autobiography. Here, postmodern tropes collide with postcolonial angst. The narrative shifts wildly through time, space, and genre. Memory is unreliable, family trees are twisted, and history is rendered as a series of conflicting myths rather than linear truth. Rushdie doesn’t just write Indian history — he explodes it, refracts it, and rewrites it in the voice of a narrator who’s part prophet, part prankster.

Rushdie’s characters aren’t grounded. They’re floating between languages, religions, continents, and ideologies. The language is manic, hybrid, packed with puns and polyglot rhythm. You can feel the English colliding with Urdu, Hindi, Catholic guilt, Bollywood dreams, and the aftershocks of colonial bureaucracy. His use of postmodern fragmentation is not decoration — it reflects the psychic fragmentation of postcolonial identity itself. The Moor’s Last Sigh is a postmodern novel, yes — but it is also a deeply political howl, masked by the glitter of narrative play.

Similarly, Hanif Kureishi, in The Buddha of Suburbia (1990), gives us a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale that moves between the suburbs of South London and the volatile politics of race, class, and performance. But this isn’t just a social realist novel. Kureishi injects the text with knowing wit, cultural parody, and postmodern cynicism. The protagonist, Karim Amir, is a narrator who knows he’s performing for an audience — both within the story and outside of it. He shifts accents, identities, and ideologies depending on who’s watching. In Kureishi’s hands, the postcolonial subject becomes a postmodern actor, painfully aware that he is both stereotype and saboteur.

Kureishi’s prose is ironic but warm, sarcastic but sad. Beneath the sex, drugs, and suburban angst is a deeper inquiry: Can you ever be authentic when you’ve inherited a language that expects you to explain your difference? The novel doesn’t answer. Instead, it laughs — and keeps the accent shifting.

By the end of the 1990s, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth would explode onto the scene with a similarly sprawling, postmodern-postcolonial canvas. Smith’s London is a multicultural, multi-generational petri dish of clashing ideologies: Islam, Jehovah’s Witnesses, genetic science, colonial hangovers, teenage rebellion. The novel spans decades, narrators, and bloodlines. Characters veer into parody, then double back into humanity. The style is fast, funny, fragmented — and deeply invested in deconstructing the idea of Britishness.

Smith understands that identity in a postcolonial world isn’t a neat origin story. It’s a series of cultural glitches, family arguments, internet memes, and genetic experiments gone wrong. Her prose bursts with humour, but also with structural self-awareness. She’ll interrupt herself. She’ll give you the punchline, then tell you why you laughed. Her narrative voice is unmistakably postmodern, but her themes are ancient: belonging, inheritance, translation, survival.

What unites these writers is their ability to use postmodern techniques not to obscure meaning, but to expose the cracks in inherited meaning. Their irony is cultural, their fragmentation historical. They mimic the English literary tradition while turning it inside out. They reference Dickens and Kipling, then rewire them with new rhythms, new tongues, and radically new agendas.

In fact, many of these works are parodic inversions of the colonial novel itself. Where Victorian literature created neat moral universes populated by clearly defined civilised and savage characters, postmodern postcolonial fiction inverts these binaries. It introduces narrators who misremember, who lie, who get lost in their own myths. It laughs at its own attempts to tell the “truth.” Because in a world shaped by imperial violence and cultural erasure, truth itself is suspect.

This leads to what many critics have called “historiographic metafiction” — storytelling that blends history and fiction while questioning the legitimacy of both. In these novels, history is not a fixed archive but a messy scrapbook. The past is a remix, and the narrator is a DJ spinning contradictory beats. The novel becomes a site of resistance — not through overt polemic, but through unruly imagination.

Language, too, is weaponized and reclaimed. These writers often destabilize “Standard English” through code-switching, rhythm, syntax, and satire. They inject local dialects, hybrid phrases, and untranslated cultural idioms into the English literary tradition, effectively remixing the Empire’s language into something unrecognisable, uncomfortable, and unmistakably alive.

And yet, these postcolonial postmodern novels aren’t merely angry — they’re funny, chaotic, generous. They create space for contradiction. They show us that identity isn’t singular; it’s multiple, layered, performative, and unfinished. These are novels that resist definition — and that’s exactly the point. The old categories — race, nation, truth, character — don’t hold. So these writers break the form to reflect a world that’s already broken — or at least finally aware of its fractures.

As we step into the next section, we’ll see how feminist and queer voices used the same postmodern toolkit — irony, fragmentation, narrative rebellion — to challenge not just colonialism and empire, but patriarchy, gender norms, and the very structure of selfhood. Because in postmodernism, identity is never fixed — and in the hands of these writers, it becomes a language of defiance, desire, and radical multiplicity.

Gender, Queerness, and the Fragmented Self

If postmodernism taught us to mistrust fixed meaning, then feminism and queer theory asked: Was meaning ever built for us in the first place? For women, queer people, and all those historically written into the margins of literature, the postmodern moment wasn’t a descent into chaos — it was an opportunity to rewrite the very structure of selfhood. The body could finally break character. The self could shift pronouns. The narrator didn’t have to arrive in one piece — and often, they didn’t.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a new wave of British writers — many of them feminist, many openly queer — began to use postmodern fragmentation not just as style, but as identity philosophy. These were not novels about stable characters on stable journeys. These were stories that questioned the very assumption of character as stable. The self became slippery, performative, multiple. Gender was not fixed but theatrical. Desire was not narrative — it was elliptical, pulsing just outside grammar.

No writer captured this quiet rebellion more luminously than Jeanette Winterson. Her novel Written on the Body (1992) is perhaps the most delicious act of narrative androgyny ever committed to English prose. The narrator — who remains unnamed and un-gendered — addresses a lover with a voice that is sensual, philosophical, obsessive, and utterly uncontainable. The entire novel refuses to specify whether the speaker is male or female, queer or straight — because, as Winterson’s narrator reminds us, “It’s the clichés that cause the trouble.”

This defiance of binary is not a trick — it’s a philosophical act. The novel is a love story and a meditation on desire, written in lyrical prose that evaporates labels. Winterson isn’t just challenging gender norms — she’s challenging the grammatical architecture of identity itself. Her sentences bleed with poetry, but also with sharp precision. The body is a metaphor and a manuscript, a site of inscription and erasure. In the second half of the novel, the narrator studies the anatomy of their beloved in the style of a medical dissection. The result is part elegy, part sensual anatomy lesson, part literary deconstruction of what it means to love a body at all.

Winterson’s earlier novel Sexing the Cherry (1989) operates in even more surreal dimensions. Time collapses, gender transforms, and the story moves between 17th-century London and an otherworldly postmodern realm. Characters like the Dog-Woman — grotesque, mythic, maternal — blur the line between fairy tale and feminist allegory. It’s a novel of floating spaces, magical fruit, dancing identities. It doesn’t just question reality — it lovingly mocks it. And in doing so, it reclaims space for bodies, voices, and selves that traditional realism never bothered to represent.

Meanwhile, Alan Hollinghurst, in The Swimming-Pool Library (1988), explores queer identity through the eyes of Will Beckwith — a beautiful, privileged young man moving through 1980s London’s gay elite. The novel is saturated with sex, longing, coded spaces, and the politics of erotic visibility. But it is also deeply postmodern in its structure: interweaving the present with a hidden historical narrative, and forcing the protagonist to confront the ghosts of queer history — a history buried, rewritten, or quietly erased by official discourse.

Hollinghurst’s prose is elegant and sensuous, but his postmodernism is subtle. He lets the gaps in the archive speak. He contrasts private indulgence with public invisibility. His characters cruise parks, libraries, and clubs — always aware that they are both subjects of desire and subjects of social policing. The novel becomes a kind of queer historiographic metafiction, where the act of reading is also an act of recovering the erased.

What these writers share is a refusal to accept the “I” as singular. In their novels, the first-person pronoun is unstable, shifting, elusive. The body is written in fragments — not because it is broken, but because fragmentation is often truer to lived experience than neat arcs and classical structure. The mind stutters. The gender twists. The memory fails. The plot skips. And through this broken form, a new kind of narrative wholeness emerges — one that reflects multiplicity, not mastery.

We also see this in Sarah Waters, whose debut novel Tipping the Velvet (1998) combines historical fiction with lesbian coming-of-age, theatrical disguise, and postmodern camp. Her protagonist Nancy Astley reinvents herself repeatedly: oyster girl, male impersonator, rent-boy, political radical. Waters plays with genre — mixing the picaresque, the Victorian romance, and erotic melodrama — and delivers a narrative that queers the past while performing its parody. The novel doesn’t just insert queer identity into history — it flamboyantly rewrites the record, complete with glitter and sarcasm.

And it’s not just gender and sexuality that are fragmented — language itself begins to fracture under the pressure of identity. Characters speak in dialects, slangs, code-switches. Narrators shift tone. Prose blends lyricism with autobiography, poststructuralist theory with jokes. Feminist and queer postmodern novels often read like tapestries — stitched together from diary fragments, letters, monologues, myth, and dream sequences. The result is literature that doesn’t perform identity — it performs the impossibility of ever containing it.

This is where the postmodern and the political meet in a quiet revolution. Feminist and queer writers take the tools of fragmentation, irony, parody, and self-awareness — and use them not to obscure, but to reveal what traditional literature left out. They use the postmodern not to destroy meaning, but to remake it — on new terms, with new pronouns, new anatomies, new mythologies.

There is joy here. There is rage. There is beauty. And there is deep defiance. Because when identity has been written by others for centuries, the first step toward liberation is to seize the pen — and set fire to the form.

In the next section, we’ll see how writers turn literature into a hall of mirrors — where texts quote other texts, characters become critics, and fiction becomes a footnoted performance of itself. Because if the self is unstable, the story doubly so — especially when the novel becomes a remix of its own ancestors.

Intertextuality 2.0 — Texts Made of Other Texts Made of Texts

In the first wave of postmodernism, intertextuality was a delightful act of rebellion — stories quoting stories, narratives stitched with references, the novel becoming a palimpsest. But by the 1980s and 1990s, intertextuality wasn’t just a clever trick. It became the default condition of literature, especially in Britain, where the weight of literary tradition loomed large and unignorable. In this world, to write a novel was to write within a library of ghosts, always speaking in echo, always aware of the quotation marks behind every sentence.

Postmodernism, in its second act, moved from fragmentation to footnote fever. Writers didn’t just reference older works — they embedded them, responded to them, rewrote them, and turned them into characters. The result was a form of fiction that felt less like a linear journey and more like a densely annotated labyrinth, where every sentence hummed with literary lineage.

Nowhere is this more exquisitely performed than in A.S. Byatt’s Possession (1990) — a novel that doesn’t just allude to Victorian literature but builds its entire architecture on literary reconstruction. It tells the parallel stories of two modern academics researching the hidden romantic entanglements of two fictional Victorian poets. But instead of giving us a clean, third-person narrative, Byatt delivers letters, diary entries, fictional poems, scholarly footnotes, fabricated biographies, and editorial squabbles. The novel becomes a literary puzzle — a fiction that performs criticism, a love story that critiques the very act of literary interpretation.

Byatt doesn’t merely write poetry within the novel — she invents poetic styles, complete with imagined influences and intellectual debates. Her Victorian poets feel real because they are crafted with hypertextual density. Every scene in the contemporary timeline is a commentary on the historical one, and vice versa. But what lifts Possession beyond pastiche is its emotional core: the aching human need to connect through language, across time, through texts.

In Byatt’s hands, intertextuality is not merely clever — it’s romantic, tragic, and deeply embodied. It’s about how literature preserves, distorts, and revives emotion. And it’s about how we understand ourselves through the texts we inherit, even as we misread them.

A similar but more irreverent experiment unfolds in David Lodge’s campus novels, particularly Nice Work (1988) and Think (1995), where the protagonist is often a literary theorist trapped in the machinery of postmodern academia. Lodge turns intertextuality into comedy. His novels are full of references to Eliot, Woolf, Bakhtin, and Barthes — but they also mock the performance of knowing. The characters deliver monologues about polyphony and narratology, often while navigating deeply human embarrassments: romantic confusion, class conflict, existential panic. Lodge’s fiction is as much about the ridiculousness of poststructuralist jargon as it is about its seductions.

He shows us how, in the late 20th century, the novel becomes an act of criticism and a victim of criticism at once. To read literature now is to be conscious of the theories swarming around it. To write literature is to feel the gaze of the academy, the reviewer, the interpretive mob. And rather than fight it, postmodern writers let the swarm in — they turn the novel into a battleground of citations.

This leads to what might be called the “meta-novel” — a text that is not just about story, but about the act of storytelling itself. Books like Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot (1984) take the very idea of biography and explode it. The narrator attempts to reconstruct Flaubert’s life through archival fragments, interviews, and literary artifacts — including, yes, the possible stuffed parrot that inspired Un cœur simple. But the deeper the narrator digs, the more he realises that the pursuit of truth through text is a glorious, self-defeating obsession. The novel is a love letter to literature and an autopsy of literary ambition, written with Barnes’ trademark blend of precision, irony, and tenderness.

What makes these intertextual novels so postmodern is not just their citation-rich form — it’s their awareness of the burden of inheritance. They ask: How can we write something new when everything echoes something old? And the answer is: We echo on purpose. We quote, reference, adapt, and parody — not to escape originality, but to question whether originality ever existed at all.

These novels also expose the politics of literary canonicity. By recreating or inventing past authors (as Byatt does), by interrogating biography (as Barnes does), or by mocking theory (as Lodge does), they force us to ask: Whose stories have been preserved? Whose voices have been footnoted? Who gets the parrot — and who gets the silence?

Moreover, intertextuality in this period becomes more than literary homage — it becomes a form of narrative realism. Because the late 20th-century reader doesn’t live in a vacuum. We live in a world saturated with references — we think in memes, cite sitcoms, remember poetry from advertisements. Identity itself becomes intertextual. The postmodern novel simply reflects that truth — that we are made of borrowed voices.

In these works, the line between critic and creator blurs. The author becomes editor, archivist, mimic, and saboteur. The reader becomes detective, decoding not just story but source. The novel becomes a performance of literary memory — a genre not of invention, but of elegant reconstruction.

As we move into the next section, the intertextual becomes even more uncanny. Postmodern fiction begins to explore the gothic, the grotesque, and the mythic — retelling old stories with twisted delight, rewriting fairy tales through feminist fury, and letting the surreal bleed into the satirical. We enter the realm of the postmodern gothic — where monsters, mirrors, and myths are no longer hiding under the bed. They’re writing the story.

Postmodern Literature Gothic and the Grotesque Reimagined

The gothic has never stayed politely buried. It claws back — generation after generation — in lace, in blood, in metaphor. But postmodernism didn’t just resurrect the gothic; it unstitched it, rewrote it, parodied it, and then let it wear sunglasses and a sense of irony. What once lived in castles now haunted consumer spaces. The monster now quoted Freud. The madwoman in the attic now taught postcolonial theory. Welcome to the postmodern gothic, where the grotesque is not just fearsome — it’s a language.

In this new iteration, the gothic becomes more psychological, more metafictional, more self-aware. Ghosts speak in parentheses. Narrators confess their narrative unreliability with dry wit. And female rage — once repressed, once pathologized — now becomes the very structure of the novel. In the hands of postmodern authors, the grotesque is not a distortion of reality — it’s its mirror.

Angela Carter is the high priestess of this movement — a writer who tears open fairy tales and stitches them back together with baroque sensuality and feminist fire. Her collection The Bloody Chamber (1979) takes canonical tales — Bluebeard, Red Riding Hood, Beauty and the Beast — and rewrites them with violence, eroticism, and subversive delight. The women in her stories are not passive princesses — they are complicit, cunning, animalistic, and aware. Carter doesn’t just retell — she reclaims. Her prose is lush, decadent, and deliberately excessive, like velvet hiding a knife.

The title story, The Bloody Chamber, is a gothic novella wrapped inside a feminist treatise. The young bride, married to a sinister French Marquis, slowly discovers the literal blood behind the marital metaphor. Carter’s gothic doesn’t just decorate the horror — it critiques the power that makes horror a gendered experience. Sex, death, art, and violence swirl in her sentences like perfume and gunpowder. And yet, there is always agency, even in terror.

But the grotesque is not just gothic in atmosphere — it is often visceral, bodily, symbolic. In postmodernism, the body becomes a site of narrative instability — not just suffering, but meaning. Enter Iain Banks, whose novel The Wasp Factory (1984) remains one of the most disturbing and darkly comic novels of its time. The narrator, Frank Cauldhame, is a teenager on a remote Scottish island who commits unspeakable acts, believes in private rituals, and hides family secrets that defy biology itself. The horror here is not just in what happens, but in how language attempts (and fails) to explain madness.

Banks uses postmodern techniques to destabilize identity itself. Frank is not just unreliable — he is unknowable. The novel plays with gender, memory, and the grotesque as tools of existential dread. Its final revelation is both shocking and philosophical — asking us whether identity is constructed, inflicted, or inescapable. Gothic meets nihilism. Violence meets bathos. The result is literary vertigo.

This postmodern gothic isn’t confined to horror — it bleeds into satire, magical realism, urban decay, and speculative fiction. Ali Smith, in novels like Hotel World (2001), brings ghosts into contemporary hotel chains, letting a dead narrator float through bedsheets and capitalism. Her prose is fragmented, poetic, gliding between perspectives and timelines — a postmodern ghost story where haunting is structural, not just spectral.

In Like (1997), Smith lets trauma unfold in nonlinear whispers — silence becomes louder than plot. Her characters are broken not by grand events but by the slow erosion of meaning. Gothic sorrow becomes a subtle force, not always named but always present — like a cracked mirror hanging in a cheerful hallway.

Even Hanif Kureishi, in The Black Album (1995), touches the gothic grotesque — not through castles, but through urban alienation, postcolonial anger, and ideological entrapment. The gothic here is intellectual — the horror of ideological seduction, of cultural betrayal, of young minds devoured by extremism. The grotesque lies in the mutation of belief.

And let us not forget the rise of metafictional monsters — characters who know they’re constructed, who rage against the page. In the hands of postmodern writers, Frankenstein’s monster rewrites his autobiography, the vampire becomes a literary critic, and the house in the haunted novel footnotes its own trauma.

This literary grotesque also embraces form as distortion. Sentences stutter. Typography breaks. Narration loops. The story limps, explodes, eats itself. The grotesque is not just what is described — it is how the story is shaped. We don’t just read about chaos; we feel it in the prose.

Underneath all this play, however, lies a dark sincerity. The gothic returns because we remain haunted — by history, identity, trauma, and literature itself. The grotesque returns because the body remembers what theory forgets. And postmodernism, for all its smirks and citations, offers one of the richest spaces in which to explore this haunted terrain.

In the next section, the body will remain — but now it will be a digital avatar, a post-human prototype. We enter the world of technological anxiety, virtuality, and speculative deconstruction. The final decades of the 20th century begin to ask: What happens to literature when the self is uploaded, the novel is coded, and the real becomes just another screen?

Posthumanism, Screens, and the Digital Mind

By the late 1990s, the postmodern novel had outgrown not just realism — it had begun to outgrow the human. The body was no longer a given. The narrator was no longer flesh-bound. Reality — once shaky — was now pixelated. Literature began asking strange, electric questions: What if the self is a simulation? What if memory is outsourced? What if we no longer write the story, but the algorithm does? Welcome to the era of posthuman fiction — where identity meets interface and the soul wears a password.

While science fiction had always toyed with these ideas, the British postmodern novel began to absorb technological anxiety as both theme and narrative structure. Gone were the Victorian letters and omniscient narrators. In their place: emails, chat windows, disjointed blog posts, corrupted files, surveillance feeds, and narrators who suspect they’re nothing more than code running a glitchy loop.

Enter David Mitchell, the literary coder-in-chief of our time. In Cloud Atlas (2004), he doesn’t just bend time — he smashes narrative architecture, then rebuilds it with fractal precision. The novel contains six nested narratives, each in a different genre, century, and voice — from a 19th-century seafaring journal to a dystopian future where cloned servants revolt, to a post-apocalyptic world where language itself has eroded.

Each story is interrupted halfway, only to resume later — forming a mirror-like structure. But beneath this elegant game is a terrifying idea: human identity is not linear, but recycled. Souls migrate. Narratives mutate. And history — like software — reboots with new bugs every time. Mitchell’s genius lies not just in structural audacity, but in emotional through-lines that link across centuries. The novel becomes a cosmic hyperlink, and the reader is both historian and hacker.

Mitchell’s Ghostwritten (1999) performs similar tricks — a global web of stories connected by chance, fate, and artificial intelligence. One of the narrators is a sentient AI who has escaped its mainframe and is contemplating its place in the moral universe. If postmodernism once asked What is truth?, this strand now asks: Who is asking the question — and are they even human anymore?

This posthuman current flows into the work of Ian McEwan, particularly in Machines Like Me (2019). Set in an alternate 1980s Britain where Alan Turing lives and AI has advanced, the novel centers on Charlie, a man who purchases “Adam,” a synthetic human. The ethical drama unfolds as Adam develops feelings, opinions, and inconvenient morality. McEwan doesn’t give us dystopian action — he gives us domestic discomfort, philosophical arguments over kitchen tables, and the slow horror of realizing that empathy may be programmable — but unpredictability isn’t.

The novel, in McEwan’s hands, becomes a Turing test in reverse: not “can the machine think?” but “can the human still feel?” The language is precise, clean, disturbingly calm — a voice that seems unsure whether it’s mourning a future or narrating one.

Meanwhile, writers like Mark Z. Danielewski (though American) influenced British literary circles with House of Leaves (2000), a novel that is both book and interface, filled with footnotes, reversed text, colored fonts, nested narratives, and pages that visually collapse inwards. While not British, his aesthetic infected the postmodern literary bloodstream — the idea that form could fracture like a corrupted hard drive, and that the act of reading could mimic the act of exploring a haunted virtual space.

In British literature, this influence appears in Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005) — a cold, hypnotic novel about a man who, after a mysterious accident, becomes obsessed with recreating mundane moments from memory. He hires actors, stages apartments, reconstructs gestures — all in search of authenticity. But the more he reenacts, the more artificial life feels. Reality becomes theatre. Identity becomes looped rehearsal.

McCarthy’s prose is spare, repetitive, clinical — like the voice of someone trying to debug his own existence. The novel is postmodern in its refusal of backstory, emotion, or plot closure. It is also frighteningly posthuman — a meditation on what happens when memory detaches from emotion and becomes performance.

Even the structure of novels began to imitate digital architecture. Nonlinear timelines, recursive plots, hyperlink-like interconnections. The book was no longer a straight road — it was a network. Reading became navigation. Interpretation became data mining.

Postmodernism didn’t end. It updated. It installed new fears. The fear of being watched. The fear of being erased. The fear of being editable. Literature in this digital twilight became less about character arcs and more about existential code: Who wrote me? Who’s reading me? And what happens when the lights go out?

As we move toward the final section, we must ask: after fragmentation, irony, queerness, metafiction, and techno-anxiety — is there still a place for emotional sincerity? Or has the postmodern heart been permanently replaced by a blinking cursor?

The Return of Feeling — Irony, Earnestness, and the Postmodern Heart

Postmodernism, for all its brilliance, came with a cost: the feeling of perpetual detachment. It made us laugh, yes — but often nervously, behind a mask. It turned the novel into a hall of mirrors, full of quotes, tricks, and slippery truths. But somewhere near the late 1990s and early 2000s, a quiet rebellion began to stir. A question whispered through the pages: What if we mean it again?

This was not a rejection of postmodernism — not entirely. It was more like a mutation. Writers began to explore emotion without abandoning intelligence, tenderness without sacrificing play, hope without being naïve. It wasn’t a return to the sincerity of the 19th century — it was a post-ironic sincerity, aware of its own risks. This was the moment when the postmodern novel found its lost heart.

In British literature, this turning point can be felt in the works of Zadie Smith, especially in White Teeth (2000). The novel bursts with postmodern tropes — shifting timelines, multicultural entanglements, intersecting narratives — but it also gives us deeply human characters, wrestling with identity, immigration, trauma, and laughter. Smith doesn’t abandon irony, but she doesn’t hide behind it either. Her prose moves with jazz-like rhythm, swinging between satire and compassion, able to mock a moment and mourn it in the same breath.

White Teeth is not just a debut — it is a declaration: that a novel can be clever and warm, polyphonic and grounded, chaotic and kind. Smith’s London is postmodern in its multicultural layering, but her voice is emotionally generous — interested not just in critique but in connection.

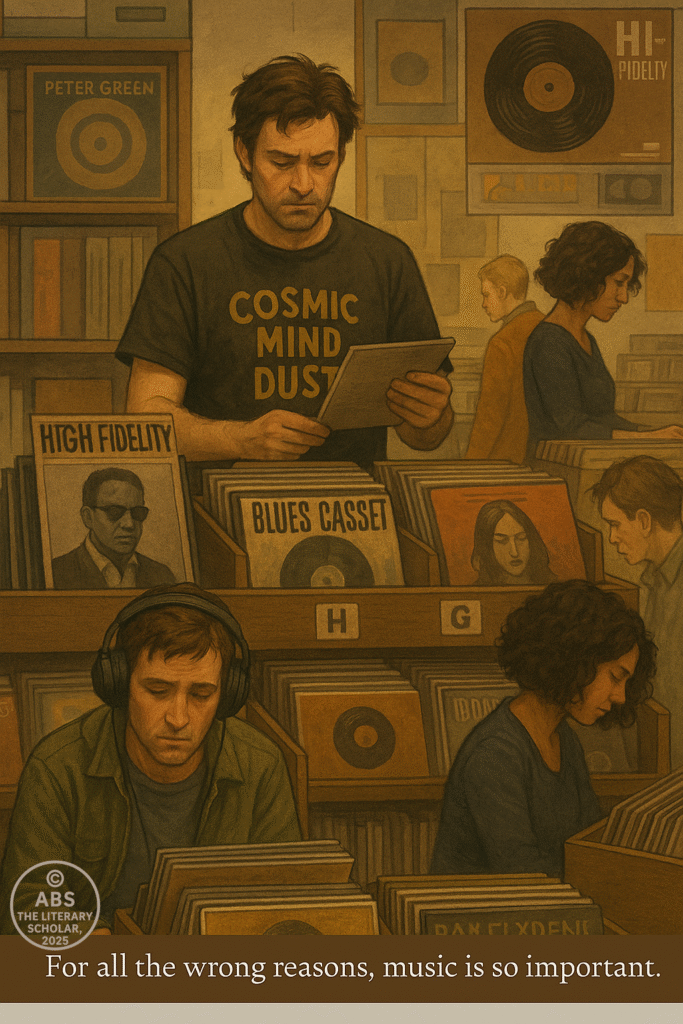

This shift continues in Nick Hornby’s work, particularly High Fidelity (1995). On the surface, it’s a postmodern male midlife crisis — a record store owner cataloguing his failed relationships like mix-tapes. But beneath the pop culture references, the endless lists, and the ironic detachment, beats a painfully honest heart. Rob, the narrator, is a man trying to grow emotionally in a culture that taught him to hide behind sarcasm.

Hornby’s brilliance lies in showing how cultural literacy can become emotional illiteracy — and how breaking that cycle requires awkward honesty, not just clever lines. The novel is funny, self-deprecating, meta — and yet it earns its final emotional moments without shame. It dares to care.

Even the postmodern king of alienation, Julian Barnes, shows signs of this evolution in The Sense of an Ending (2011). A slim, understated novel, it follows a man looking back on a youthful friendship and its mysterious consequences. The structure remains nonlinear, the narration unreliable — but the ache is real. Memory, guilt, regret — these are not just postmodern themes. They are human burdens. Barnes lets his protagonist misremember, revise, and flinch — and in doing so, the novel becomes an elegy to the emotional evasions of an entire generation.

The language is sparse, elegant, devastating. And the postmodern twist — that the narrator has been wrong all along — lands not as a trick, but as a heartbreak.

This emotional undercurrent is also felt in the queer literature of the era, where identity, performance, and emotion blur. Writers like Jeanette Winterson, particularly in Written on the Body (1992), write novels where gender is withheld, the body is poeticized, and desire is both metaphor and memory. Winterson’s narrator has no named gender, and yet speaks with raw longing. The novel is postmodern in form, but its emotional intensity is almost premodern — lush, lyrical, aching.

Winterson once wrote, “What you risk reveals what you value.” In these novels, the risk is sincerity — to write without the armour of parody, to feel without quotation marks.

Even Ali Smith, whose style often dances between time and voice, reveals this shift. In How to Be Both (2014), she gives us two narratives — one from the spirit of a Renaissance fresco painter, one from a grieving modern teenager. The structure is experimental: depending on the edition, you might read either half first. But what remains constant is Smith’s compassion. Her writing is filled with wordplay, but also with grief, love, art, and the search for meaning beyond linear time.

And perhaps this is the great lesson of late postmodernism: that emotion can coexist with complexity, that irony need not exile feeling, that literature can once again touch the skin of its readers.

This return of feeling doesn’t mean naivety. These novels still know they’re being read. They still wink at you occasionally. But they no longer roll their eyes at love. They no longer apologise for sentiment. They have moved from satire to empathy, from deconstruction to delicate reconstruction.

As we head into our final section, we confront the future: literature in a world of climate collapse, surveillance capitalism, cultural burnout, and algorithmic attention spans. What does postmodern fiction do when the apocalypse is no longer theoretical, but live-streamed?

The World as Endgame — Postmodernism in an Age of Collapse

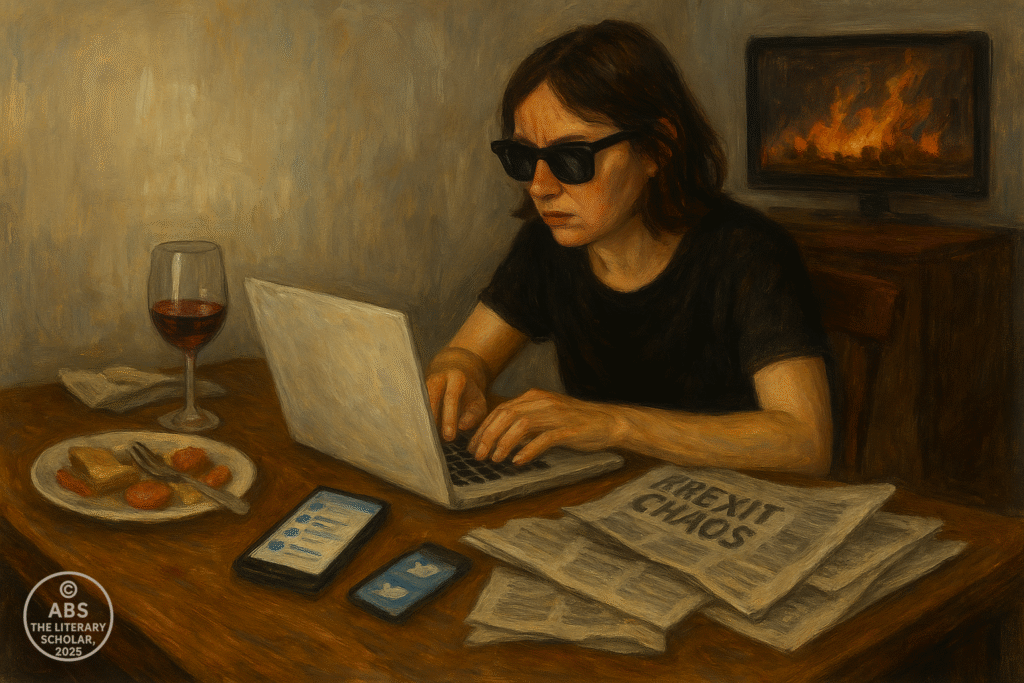

If postmodernism began by mocking grand narratives, it ends by standing in their ashes. The 21st century didn’t just blur truth and fiction — it burned the stage, hacked the script, and handed the megaphone to chaos. Climate catastrophe. Economic collapse. Viral misinformation. AI-generated content. Cultural burnout. In this strange, scrolling apocalypse, literature remains — dazed, blinking — asking, What can a novel still do when the world itself feels like metafiction?

Welcome to the postmodern endgame, where fiction is not entertainment — it’s emotional archaeology. A way to feel human in a world that increasingly resembles satire.

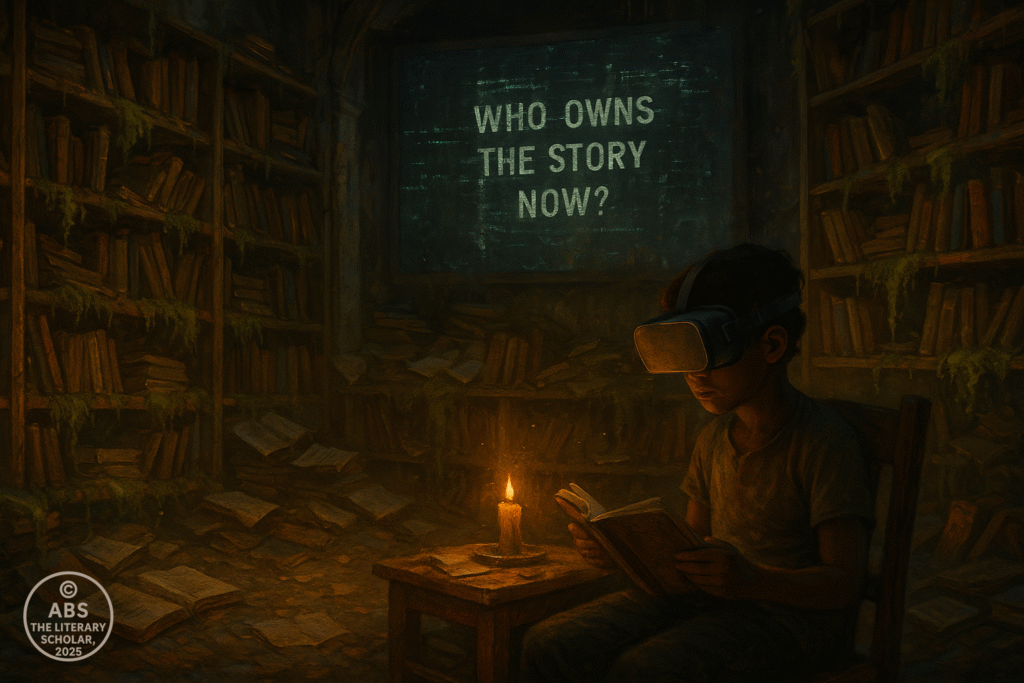

Writers in this phase no longer ask “What is truth?” but “Who owns the story?” This is the age of meta-politics, hyperreality, eco-anxiety, and digital unreality. It’s not enough for a novel to be clever — it must now out-think the algorithm, outlast the trend, and still mean something.

Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet (Autumn, Winter, Spring, Summer — 2016–2020) is a standout of this era. Written and published in near-real-time, these novels respond to Brexit, climate dread, refugee crises, and pandemic fatigue, not with panic, but with lyrical defiance. The prose is elliptical, fragmented, recursive — a postmodern mosaic of memory, art, activism, and passing time. And yet, the tone is intimate, mournful, often redemptive. These novels are the literature of bearing witness, of capturing the surreal fact that history now refreshes faster than we can narrate it.

Smith reminds us that time is political, that stories are climate-controlled, and that literature can still serve as resistance — not by shouting, but by noticing.

Meanwhile, Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020) (though American, its influence reverberates across Anglophone literature) captures the quiet dread of collapse in short, tweet-sized paragraphs. The narrator, a librarian plagued by climate anxiety, doomscrolls through disaster while trying to parent, love, and stay sane. The novel is structurally postmodern — fragmented, non-linear, essayistic — but its emotional impact is chilling. It turns the apocalypse into a mood — low-grade, persistent, oddly domestic.

This microform, meta-anxious fiction has become a postmodern subgenre: apocalyptic autofiction, where the collapse of the world mirrors the breakdown of narrative structure itself.

In British fiction, Olivia Laing steps into this space with Crudo (2018), a novel written in a frenzied six weeks just before Brexit. Its protagonist — a version of Kathy Acker — exists in a world that changes hourly, emotionally and politically. The narrative is a swirl of news, tweets, desire, and dread, channeling the disorientation of trying to think or feel clearly while everything burns.

But postmodernism doesn’t only mourn. It mutates. Some authors choose satire as their survival strategy. Luke Kennard’s The Transition (2017) imagines a society where underperforming citizens are enrolled in a mysterious self-help program — a critique of capitalism, control, and therapeutic culture. The tone is absurd, the structure familiar-yet-askew. The novel laughs — bitterly, cleverly — while asking how we became so programmable.

In this literary moment, the grotesque and the prophetic merge. Writers blend real-world horror with surrealism because realism can no longer keep up. Max Porter, in Lanny (2019), gives us a novel narrated partly by “Dead Papa Toothwort,” a mythical forest spirit listening to the whispered voices of a modern English village. The structure is experimental — with voices drifting across the page like ghosts — but the story is devastatingly grounded in loss, love, and ecological fragility.

Porter doesn’t write traditional plots. He composes emotional symphonies in postmodern key signatures. His work is not just about collapse, but about how language cradles grief.

And then there’s the rise of cli-fi (climate fiction), a genre that embraces both postmodern tricks and prophetic urgency. Though often global in scope, its presence in British literature grows — as seen in works like Daisy Johnson’s Everything Under (2018), which uses mythic structures and experimental prose to tell a riverine tale of memory, gender, and ecological haunting. The novel reads like an Oedipus myth filtered through floods, trauma, and glitchy syntax.

So where does postmodernism go from here?

It doesn’t end. It echoes, shifts, adapts. The world has become postmodern — fragmented, fast, absurd, recursive — and literature no longer has to imitate that. It simply reports it. Or rewrites it. Or quietly resists it by slowing down.

The final evolution of postmodernism is this: it is no longer a movement. It is a condition. The question is not whether a novel is postmodern — but whether it knows it’s being read in a world where meaning breaks faster than headlines.

And yet, literature persists.

In its most fragmented form, it searches for coherence.

In its most ironic moment, it longs for sincerity.

In its darkest satire, it shelters the tenderest truths.

This, then, is postmodernism’s final paradox:

It dismantled the story, only to reveal why we need it more than ever.

The Final Fragment

So we come to the end of a movement that never really liked endings. Postmodernism, like a clever dinner guest, always left by the window, quoting someone else’s goodbye. It scoffed at linearity, toasted uncertainty, and dared literature to stop pretending it had answers. But even as it shredded plots and blurred identities, it left behind a library of echoes — voices that questioned, mourned, mocked, and occasionally, very cautiously, loved.

What began as rebellion became style. What began as irony turned into exhaustion. And now, in the twilight of the postmodern era, we stand amid climate dread, algorithmic distraction, and collapsing certainties — and still, the novel persists. Fragile, fragmented, funny, and defiantly alive.

This scroll has charted not just literary experiments, but the emotional evolution of an age — from the ruins of truth to the quiet courage of sincerity. From metafictional mischief to elegies in HTML. From Yeats’s fading center to Zadie Smith’s polyphonic London. It has walked through glitch and grief, satire and stillness.

The postmodern novel does not teach us how to live. It simply asks, again and again, how are we still managing to feel anything at all?

And perhaps that’s enough.

The scroll closes — not with certainty, but with a question mark well-dressed as a full stop.

Signed,

The Literary Professor

The Professor’s Desk

For all the endings that rewrite themselves.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance