Postmodern British literature : From Fragmentation to Irony—How English Literature Stopped Making Sense (On Purpose)

From The Professor's Desk

Once upon a time, literature had rules. Stories had beginnings, middles, and ends. Heroes quested. Tragedies wept. Realism ruled. And then… the post-war world blew all that to bits—again. But this time, the pieces weren’t just picked up and reassembled. They were deliberately left scattered. Welcome to Postmodernism British Literature, the literary movement that laughed at coherence, loved pastiche, and made art out of uncertainty. In this wild new world, everything was suspect—language, authorship, even reality. And instead of repairing the cracks, postmodern writers moved in, hung mirrors on the walls, and charged admission.

Born in the embers of the Second World War and grown in the shadow of the Cold War, consumerism, and media saturation, Postmodern British Literature shrugged off the modernist melancholy and replaced it with irony, play, and a gleeful refusal to commit to one truth. It is the era of metafiction, unreliable narrators, pastiche, paranoia, and texts that know they’re texts. This first wave of postmodernism from the 1960s to 1980s is a maze—brilliant, baffling, and endlessly self-aware. So bring your sense of humor, suspend your faith in narrative, and don’t bother asking what it means.

And thus begins our literary circus—where the tents are made of quotation, the clowns are narrators, and the ringmaster is missing. Philosophy, once the loyal butler of clarity, now moonlights as a trickster. Postmodernism takes the fragments left by modernism and doesn’t try to reassemble them. It juggles them.

In the sections to follow, we’ll see how these ideas leap off the academic page and straight into novels that glitch, plays that talk back, and characters who refuse to behave.

“Postmodern British literature emerged after the modernist period and explored irony, fragmentation, and narrative disruption.”

Get ready. The funhouse is just getting started.

The Philosophy Behind the Madness

“Truth is a matter of perspective. And perspective? That’s just the lens someone forgot to clean.”

— A postmodern philosopher, probably.

Once upon a more optimistic literary age, philosophy was the scaffolding of sense-making. Literature drew its strength from the noble ideas of rationalism, realism, and reliable truths. But by the time the mid-20th century rolled in, dragging two world wars, the Holocaust, atomic bombs, Cold War espionage, and the rise of consumerism behind it like a noisy baggage trolley at Heathrow, the scaffolding had rusted. And the builders—writers, philosophers, artists—looked at the mess and asked:

“What if meaning was never solid to begin with?”

That’s where the postmodern philosophical engine starts: not with certainty, but with skepticism. Not with grand narratives, but with their joyful demolition.

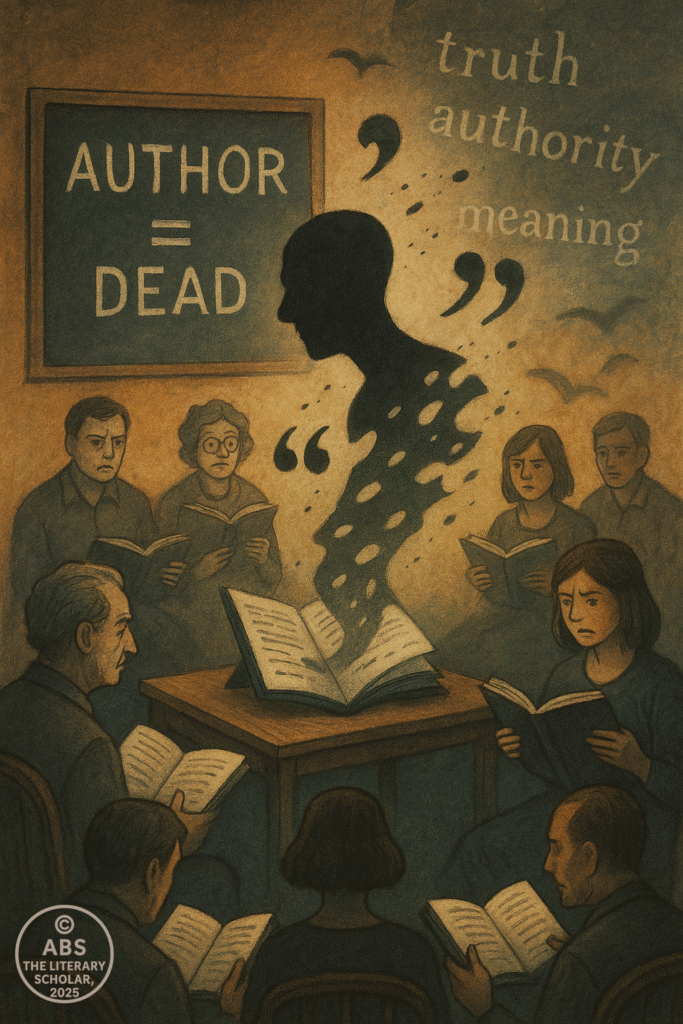

1. The Death Of The Author – Roland Barthes Sends Writers to the Gulag

In 1967, French literary theorist Roland Barthes declared that “the author is dead.” This wasn’t a homicide report. It was a revolutionary idea.

What Barthes meant was this: The meaning of a text does not reside in the mind or intention of the writer. Instead, it is born in the act of reading. The reader brings their own experiences, beliefs, and absurd 3 a.m. coffee-stained thoughts to the table. So, stop asking, “What did the author mean?” and start asking, “What do YOU find in it?”

This seemingly liberating idea gave literature its very own democracy. But it also opened the door to a thousand interpretations and zero accountability. The author was no longer the authority. The reader became the decoder.

“A text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.” — Roland Barthes

So, if you read Alice in Wonderland and think it’s a proto-feminist vegan manifesto, congratulations! You’re postmodern now.

2. Derrida’s Deconstruction – Language Has Trust Issues

Next came Jacques Derrida, who looked at language and said: “Well, that’s not what it seems either.”

With his slippery concept of “différance” (which sounds like “difference” but wears French perfume), Derrida argued that:

Words don’t have fixed meanings.

They only exist in relation to other words.

Meaning is always deferred, never quite there—like the bus you swear you just missed.

This was not just clever linguistic mischief. It meant that literature, like life, is unstable, shifting, and ultimately unknowable. So, when you read a sentence, you’re not reading a message—you’re playing a game.

“There is nothing outside the text.” — Derrida

This didn’t mean reality is fake. It meant that reality is filtered through language, and language is… well, a bit of a pathological liar.

3. Lyotard’s Grand Narrative Breakdown – No More Fairy Tales for Grown-Ups

In 1979, Jean-François Lyotard wrote The Postmodern Condition and gave us the phrase that makes English majors salivate:

“Incredulity toward metanarratives.”

A metanarrative is a big, overarching story that explains everything—religion, science, Marxism, Enlightenment, etc. According to Lyotard, postmodernism begins when we stop believing in these totalizing truths. The world is too complex, too fragmented, too full of TikTok and tacos to be explained by one story.

Postmodernism, then, is suspicious of certainty. It prefers local truths over universal laws. It questions authority—including the authority of literature, genre, logic, and even good taste.

This is why postmodern novels often refuse resolution. Because in a world with no grand narrative, closure is a myth—like guilt-free chocolate or a quiet WhatsApp group.

4. Michel Foucault – Power, Knowledge, and Why You Shouldn’t Trust Institutions

And then, there was Foucault, who didn’t just want to shake the foundations of knowledge—he wanted to trace how those foundations were built to control you.

For Foucault:

Knowledge is not neutral. It’s shaped by power structures.

Discourses (ways of talking and thinking) are tools of social control.

Literature is a site where power plays out, not where truth is revealed.

This is the postmodern shift: from “What is true?” to “Who gets to say what’s true—and why?”

“Where there is power, there is resistance.” — Foucault

In literature, this leads to characters who resist narrative control, narrators who question themselves, and stories that critique the very act of storytelling. Think The Handmaid’s Tale, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, or even the punk-energy of Trainspotting.

5. Reader-Response Theory – Your Brain is the Plot Twist

With the author dead, the text slippery, and power structures corrupt, who’s left?

You, dear reader. You’re the new star of the literary show.

Reader-response critics like Stanley Fish and Wolfgang Iser argued that a work of literature doesn’t exist until it is read. The act of reading completes the text. It’s not just about decoding meaning—it’s about participating in the construction of it.

That’s why postmodern works often feel like literary playgrounds or puzzles—because they expect you to play, not just sit and absorb.

6. Language Games and Reality TV – Literature Realizes It’s on Camera

6. Language Games and Reality TV – Literature Realizes It’s on Camera

All this philosophical groundwork leads to a dazzling truth: postmodern literature doesn’t trust language—but it still uses it to make jokes about itself.

It knows it’s a construction. It knows it’s being watched. It’s like a reality show contestant who stares directly into the camera while pretending to be shocked.

Think of it this way:

Modernism broke the rules.

Postmodern laughed at the idea of rules.

And thus begins our literary circus—where the tents are made of quotation, the clowns are narrators, and the ringmaster is missing. Philosophy, once the loyal butler of clarity, now moonlights as a trickster. Postmodernism takes the fragments left by modernism and doesn’t try to reassemble them. It juggles them.

In the sections to follow, we’ll see how these ideas leap off the academic page and straight into novels that glitch, plays that talk back, and characters who refuse to behave.

Get ready. The funhouse is just getting started.

The Rise of the Anti-Novel and Metafiction

“Once upon a time… Or not. Maybe. Who’s asking?”

— Every postmodern novel, ever.

Postmodernism didn’t just reject meaning—it rejected form. The traditional novel, with its linear plotlines, well-developed characters, tidy resolutions, and smug omniscient narrators, was no longer seen as a vehicle of truth but a fossil of outdated ideals. The postmodernists picked up this fossil, painted graffiti on it, set it on fire, and called it art.

Thus was born the Anti-Novel: a literary species that refused to act like a novel.

And along with it came Metafiction—fiction that knows it’s fiction, and wants to make sure you know it too.

1. What Exactly Is an Anti-Novel?

An anti-novel is a rebellious form of fiction that:

Rejects plot, character arcs, or moral clarity

Questions whether any “story” is real or reliable

Often disrupts grammar, punctuation, or structure for effect

Frequently breaks the fourth wall, reminding readers they are reading a text

Where traditional novels aim to immerse the reader, the anti-novel yanks you out of the dream and winks at you.

“Don’t believe a word I say,” says the anti-novel. “I’m just paper and ink pretending to be profound.”

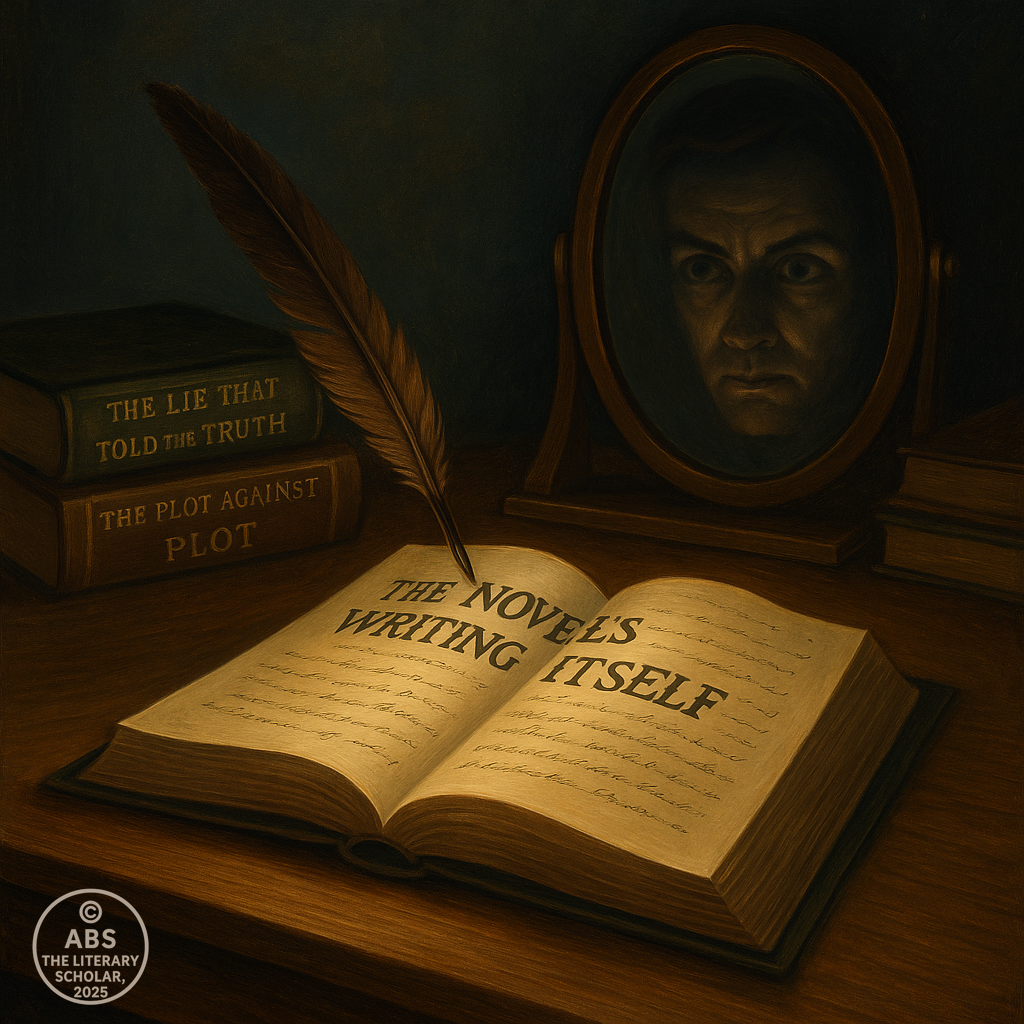

2. Metafiction: When Fiction Becomes Self-Aware

Metafiction is the literary equivalent of a character in a film turning to the camera and saying,

“None of this is real. Also, the director’s having a nervous breakdown.”

Metafiction deliberately:

Draws attention to its artificiality

Interrupts its own narration

Exposes the act of writing within the story

Comments on its own creation or authorship

“This story is about a man who wanted to write a story. The man is me. The story is this.”

Think of it as the novel gazing into a mirror—then smashing that mirror and writing about the shattering.

3. John Fowles and the Literary Striptease

One of the most elegant early practitioners of metafiction in English literature was John Fowles, particularly in his seminal work The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969).

Here, Fowles:

Inserts himself into the narrative

Offers multiple endings

Stops the plot midway to discuss Victorian social norms

Deliberately refuses closure

He famously writes:

“This story I am telling is all imagination. These characters are figments of my imagination… They never existed.”

And yet, they feel painfully real—because postmodernism loves this paradox. Fowles takes the Victorian novel and dismantles it with Victorian-style prose, leaving readers wondering: Is this a story or a lecture on the nature of stories? (Answer: both.)

4. B.S. Johnson and the Novel in a Box

B.S. Johnson (whose name sounds fictional, but isn’t) took postmodernism to experimental extremes. His novel The Unfortunates (1969) was published in a box with 27 loose chapters—to be read in any order, except the fixed first and last ones.

This wasn’t a gimmick. It was a sincere attempt to mimic the fragmented nature of memory and grief. Johnson believed the traditional novel was dishonest. “Telling stories is telling lies,” he famously declared.

So instead, he gave us a literary shuffle, where structure becomes emotional chaos.

“Life does not tell stories,” said Johnson. “Why should novels pretend to?”

5. Julian Barnes and the Parody of Truth

In Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), Julian Barnes constructs an entire novel around a dead author’s pet parrot. But is it the parrot? Is there a parrot? Or is this all just commentary on our obsession with facts and meaning?

The novel:

Offers conflicting biographical accounts

Mixes fiction and literary criticism

Challenges the idea that truth can be pinned down

Barnes writes:

“Books say: she did this because. Life says: she did this. Books are neat, life is not.”

Welcome to postmodernism, where messiness is the message.

6. Muriel Spark and the Puppet-Master’s Hand

In The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), Muriel Spark shows how narration itself can be tyrannical. The story is narrated with slippery omniscience, veering in and out of time and perspective. The titular character tries to control her students’ lives like a novelist, and the novel mirrors this theme with narrative manipulation.

Spark doesn’t just tell a story—she questions the ethics of telling it. Who gets to tell a life? And who edits the truth?

7. Other Tricksters of the Anti-Novel

Iain Banks (The Wasp Factory) — unreliable narrator, twisted timelines, gruesome metafiction

Angela Carter — uses fairy tales, myth, and grotesque sensuality to retell and deconstruct narrative tropes (The Bloody Chamber)

Christine Brooke-Rose — linguistically acrobatic novels like Between and Out, pushing language to its limits

Christine Brooke-Rose even rewrites point of view itself: one of her novels has no verbs in the past tense.

8. What All This Means (Or Doesn’t Mean)

So why all this chaos?

Because postmodern literature doesn’t believe:

That life is linear

That truth is singular

That stories should soothe or teach

Instead, it:

Mirrors reality’s absurdity

Exposes the cracks in meaning-making

Invites you to co-create the reading experience

Postmodern literature is like IKEA furniture. The writer gives you all the parts, and you assemble the meaning. Without instructions. While questioning the idea of furniture.

As the anti-novel rose and metafiction smirked its way into every bookshelf, literature stopped asking “What happened?” and started asking “What is ‘happening’ even supposed to mean?”

In the next section, we’ll see how time itself collapses, chronology becomes optional, and stories twist themselves into beautiful, baffling knots—just to make a point, or sometimes, to prove that there isn’t one.

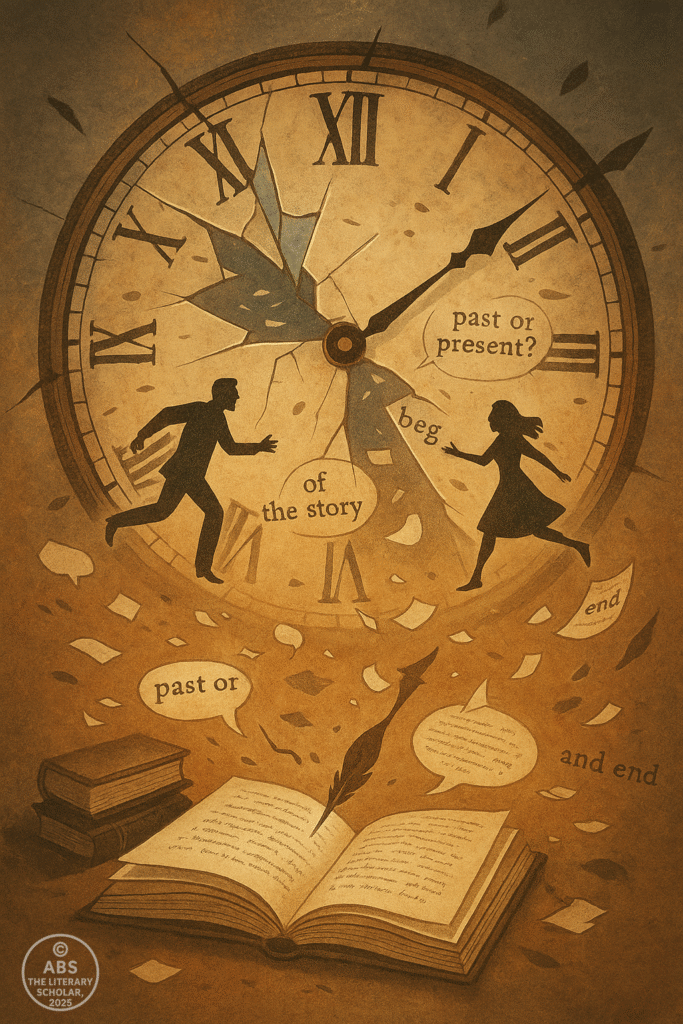

Time Gets Twisted — Nonlinear Narratives and Fragmentation

“The past is a story we keep editing. The future is a draft. And the present? That’s just the glitch in between.”

Once upon a time, time moved forward. In fiction, you began at the beginning, suffered in the middle, and either died or got married at the end.

But Postmodernism, ever the mischievous disruptor, looked at this neat linear timeline and said:

“What if we scrambled it like bad eggs in a broken clock?”

Gone is the chronological comfort of rising action, climax, and resolution. Instead, we now enter a world of looped memories, shattered plots, recursive timelines, and narrative Möbius strips.

Because, in a world where truth is unstable, why should time behave?

⌛ 1. The Chronology Rebellion – Who Needs Sequence Anyway?

The traditional narrative relies on temporality—events follow a causal order, and we feel safe knowing which part of the story we’re in.

Postmodern writers deny you that luxury.

Flashbacks become flash-sideways.

Foreshadowing collapses into hindsight.

Endings arrive mid-book.

Time in postmodern fiction is fragmented, nonlinear, and sometimes circular—not because the authors are confused, but because they want you to be.

Postmodern time is not a river. It’s a shattered mirror.

2. Jeanette Winterson and the Loop of Identity

In Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985), Jeanette Winterson blends autobiography, myth, and metaphor into a narrative that constantly fractures and reforms.

There are no chapters—only Bible-style sections (Genesis, Exodus, etc.)

Reality bleeds into fairy tale and fantasy

The protagonist’s past is never stable—it’s rewritten through memory, metaphor, and emotion

Winterson once said:

“I’m telling you stories. Trust me.”

Which is the most untrustworthy statement in postmodernism. Because storytelling isn’t truth—it’s performance.

3. Angela Carter’s Fragmented Fairytales and Feminist Time Machines

In works like The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter takes familiar myths and fairy tales and explodes them into sharp, glittering fragments.

Time becomes mythical, dreamlike, and symbolic

The narrative doesn’t develop—it mutates

Carter’s stories echo, refract, parody, and subvert

These aren’t stories you follow. They’re stories you fall into—like a hall of mirrors in a Gothic cathedral lit by disco lights.

4. Graham Swift’s Waterland: History as a Whirlpool

In Waterland (1983), Graham Swift presents history not as a linear timeline, but a circular swamp—fluid, muddy, and impossible to wade through cleanly.

The narrative jumps between generations, geographies, and griefs

Time spirals inward rather than forward

Memory is not a recollection, but an act of narrative resistance

Swift writes:

“History begins only at the point where things go wrong.”

And so the novel begins after the story has already crumbled, with the narrator trying to pick up pieces of his past and failing, gloriously.

5. The Fragment as Form – Why Wholeness Is Suspicious

Postmodern fiction is fragmented not just in structure but in philosophy.

Life is fragmented, so the novel should be too.

Coherence is seen as a false comfort, not a literary virtue.

The narrative is not a highway—it’s a map of potholes.

Fragmentation is the postmodern aesthetic of broken beauty.

This leads to:

Paragraphs that float

Sentences that interrupt themselves

Sections that begin mid-thought and never end

These stylistic tics aren’t laziness—they’re statements.

6. Multiplicity of Perspectives – When Everyone’s Right and Wrong

Rather than offering a unified voice, postmodern novels often contain:

Multiple narrators

Contradictory truths

Simultaneous realities

Everyone’s voice matters. And no one is reliable.

The result? A text that reads like a courtroom of conflicting testimonies, where even the author isn’t sure what’s going on.

Think of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying filtered through postmodernism and given a microphone in a philosophy class taught by Kafka.

7. Narrative Collage and Cut-Up Technique

Inspired by William S. Burroughs, the cut-up technique takes written text, slices it into pieces, and reassembles it randomly. It’s Bauhaus meets dada meets blackout poetry on speed.

Though more prominent in American literature, British postmodernists like B.S. Johnson and Ann Quin flirted with this form—producing prose that felt like channel surfing across genres, styles, and temporal zones.

It was chaotic, yes. But also shockingly intimate—because what is memory if not a jumbled montage?

8. Time, Trauma, and the Refusal to Heal

Postmodern narrative disorder is often rooted in psychological trauma.

Fragmented time mimics fractured identity

Nonlinearity reflects emotional disorientation

Stories avoid closure because trauma doesn’t resolve—it echoes

This is literature that acknowledges:

Healing is not neat. Memory is not accurate. Time is not your friend.

9. What Reading Postmodern Time Feels Like

Imagine this:

You open a book.

The middle is the beginning.

The narrator dies but keeps talking.

The story references itself before it happens.

The ending changes when you reread it.

You’re not lost.

You’re just postmodern.

In the postmodern novel, time is no longer a path—it’s a playground, a trap, a fog. Authors don’t guide—they disorient. Plots are not maps but mirrors, shattering under the weight of subjectivity. This isn’t a bug in the system. It’s the point.

As we move forward, prepare for the next form of rebellion: where genres start dressing up as each other, pastiche becomes the new originality, and literature takes up a part-time job as its own parody.

Genre Gets Mocked — Pastiche, Parody, and Intertextual Play

“Stealing is wrong. Unless it’s done ironically, with footnotes.”

— A postmodern motto, stitched onto every metafictional bathrobe.

If Modernism broke the rules to discover deeper meaning, Postmodernism laughs and says:

“There are no rules. And if there were, we’d quote them, remix them, parody them, and turn them into a sitcom.”

This section is where literature becomes a shape-shifter. Where a detective novel suddenly moonlights as philosophy. Where a historical epic wears a sci-fi wig. Where genre conventions aren’t followed — they’re played like jazz.

Welcome to pastiche, parody, and intertextuality — the three literary tools of the postmodern magician.

1. Pastiche — The Art of Imitation Without Apology

Let’s start with the word itself:

Pastiche is not plagiarism. It’s a celebration of borrowed forms.

It involves:

Combining multiple genres, styles, or voices

Imitating older literary modes (gothic, epic, romance, etc.)

Juxtaposing high culture with low culture for comic or chaotic effect

In the hands of a postmodern writer, a novel might be:

Part biography

Part myth

Part sci-fi

Part soap opera

And entirely aware of the absurdity

“Originality is dead. Long live collage!”

2. Parody — Literature Rolls Its Eyes (But Lovingly)

Parody is pastiche’s sassier cousin. It doesn’t just imitate — it mocks, critiques, and dismembers the original.

But unlike satire, parody in postmodernism is often done without moral superiority. It’s playful, affectionate, self-aware.

Think:

Tom Stoppard turning Hamlet into Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Angela Carter rewriting Little Red Riding Hood with feminist fangs

Julian Barnes impersonating Flaubert while questioning biography itself

Postmodern parody doesn’t say “Look how stupid this is.”

It says, “Look how ridiculous and wonderful this all was — and still is.”

3. Intertextuality — When Books Talk to Each Other (and Gossip About You)

Coined by Julia Kristeva, intertextuality is the idea that:

No text exists in isolation

Every story is a remix of previous stories

Meaning is born through dialogue with other texts

In other words:

Every book you read is haunted by other books. And some of them brought snacks.

This leads to:

Novels referencing other novels explicitly

Characters walking out of one text into another

Writers using entire genres as commentary

Postmodern texts are libraries in disguise, and readers are expected to decode the echoes.

4. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose — Murder in the Library of Babel

Umberto Eco, semiotician extraordinaire, wrote The Name of the Rose (1980) as a medieval murder mystery.

But beneath the surface:

It’s a detective novel parodying Sherlock Holmes

It’s a theological argument disguised as fiction

It’s a critique of censorship, language, and faith

And it includes a library so large, even Borges would need Google Maps

Eco writes:

“Books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told.”

His work is not just intertextual — it’s hypertextual before hyperlinks were invented.

5. Salman Rushdie — Myth Meets Masala

In Midnight’s Children (1981), Salman Rushdie:

Blends history with magical realism

Parodies the epic novel

Imitates Bollywood, folklore, and political drama

Uses pastiche to show the messiness of postcolonial identity

Rushdie’s narrator Saleem Sinai is not just unreliable — he’s melodramatic, contradictory, and deeply intertextual, referencing Dickens, Gandhi, Shiva, and spiced pickles all in one sentence.

“Reality is a question of perspective; the further you get from the past, the more concrete and plausible it seems – but as you approach the present, it inevitably seems incredible.”

This is parody with teeth. Pastiche with politics. Literature with chutney.

6. Tom Stoppard’s Drama of Double Meanings

In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), Tom Stoppard:

Rewrites Hamlet from the point of view of two minor characters

Embeds absurdist philosophy into Shakespearean tragedy

Juggles existential crisis with vaudeville comedy

The play questions:

Fate

Free will

The artificiality of theater itself

“Life is a gamble, at terrible odds — if it was a bet, you wouldn’t take it.”

That’s not just existentialism. That’s genre parody performing a cartwheel on the edge of nihilism.

7. High Meets Low — Trash Lit and Canon Texts Swap Clothes

One of postmodernism’s signature moves is blending “serious” literature with pop culture.

Examples:

Sci-fi tropes in literary fiction (Doris Lessing’s Canopus in Argos)

Pop song lyrics as poetic metaphors

Detective fiction used to frame poststructuralist theories (Foucault’s Pendulum)

Graphic novels that quote Shakespeare and Freud in one panel (Watchmen)

The message?

There’s no cultural hierarchy anymore. The soap opera and the sonnet now drink at the same bar.

8. The Novel as Mashup — Forms Within Forms

Postmodern novels frequently become:

Fake biographies (A.S. Byatt’s Possession)

Academic papers (David Lodge’s campus novels)

Textbooks, diaries, footnotes, glossaries, interviews, and indexes

Sometimes all at once

These are not gimmicks. They reflect the multiplicity of perspective, the fragmented self, and the idea that truth lies somewhere between a bibliography and a punchline.

Postmodernism doesn’t destroy genre—it dismantles it with love. It dresses up literature in pastiche, tickles it with parody, and then hands you a guidebook written in invisible ink. It invites you to laugh, decode, and question—not just the text, but your expectations of what a story should be.

And now that we’ve turned genres inside-out, let’s head into the next twist: narrators who can’t be trusted, authors who disappear, and stories that deliberately lie to you.

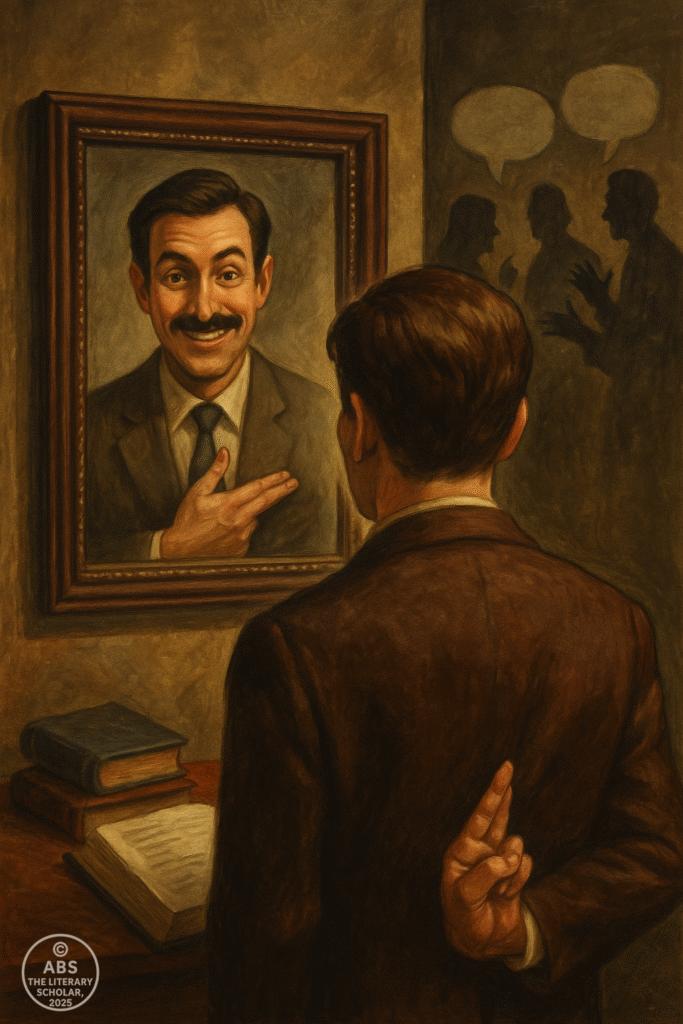

The Unreliable Narrator and the Author in Hiding

If the postmodern novel were a party, the narrator would be the charming guest who offers you champagne, tells you ten different stories about where they’re from, and then slips out the back door just before midnight, leaving you to wonder if they ever existed. Welcome to the age of the unreliable narrator — the voice you can’t quite trust, the version of events you should never accept at face value, and the literary technique that perfectly reflects a world in which subjectivity has dethroned objectivity.

In traditional fiction, the narrator was often God-like — omniscient, consistent, and invested in your understanding of the truth. But in the postmodern landscape, truth itself is on trial, and narrators are either too biased, too broken, or too self-conscious to guide you safely. Instead, they perform, distort, manipulate, and sometimes outright fabricate — not to deceive maliciously, but to reflect the fractured, post-truth world we now inhabit. And of course, in classic postmodern fashion, they often tell you they’re doing it, just to complicate things further.

Take, for instance, Graham Swift’s Waterland. The narrator, Tom Crick, a history teacher whose life is falling apart, weaves his personal tragedies into a whirlpool of fens, eels, and drowned memories. But as his version of the past becomes increasingly suspect, readers begin to question what is history, what is myth, and what is the desperate storytelling of a man trying not to unravel. Swift doesn’t offer narrative closure — he offers narrative survival. And survival, in postmodernism, is often the only resolution you get.

Similarly, Julian Barnes, in Flaubert’s Parrot, gives us a narrator obsessed with Gustave Flaubert — or more accurately, with the impossibility of knowing Flaubert. His quest for “truth” about the writer becomes an absurd exercise in contradiction, as he collects anecdotes, footnotes, trivia, and conflicting accounts about the French novelist’s life, until the pursuit itself becomes a parody. Barnes cleverly undermines the whole genre of biography, reminding us that the line between fact and fiction is paper-thin, and often, only the footnotes admit it.

But the game deepens when the author disappears altogether — not just metaphorically, as in Barthes’ theoretical pronouncement, but narratively. Enter Muriel Spark, whose The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie contains a narrator who lurks just beyond the veil, skipping through time with unnatural ease and offering cryptic commentary without ever revealing their own identity or motivation. The reader is left to navigate the tension between narrative control and narrative ambiguity, between Spark’s deliberate elisions and the quiet horror beneath the elegance. You never quite know who’s telling the story — but you always feel their hand turning the screws.

This withholding of authorial presence isn’t just playful; it’s deeply philosophical. Postmodernism sees authority as suspect, and the author — once the grand architect of meaning — now retreats into the wallpaper. Writers like John Fowles, in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, toy with this disappearance by occasionally inserting themselves back into the narrative, offering sly winks, contradictory endings, and meta-narrative digressions. Fowles admits his characters are inventions, yet treats them with the seriousness of real historical figures. He becomes both god and ghost — visible and vanished at the same time.

Even more unsettling are the narrators who don’t know they’re unreliable, who speak with such sincerity that their distortions become a form of self-deception. In novels like Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory, we begin with trust and end with unease, as the protagonist reveals — bit by brutal bit — that the world we thought we were reading was an illusion built on trauma, repression, and secrets too terrible to say aloud. The effect is unnerving because the lie isn’t just told to us — it’s told within the character, making truth an internal war zone.

All of this culminates in a central postmodern assertion: stories are shaped not by what happened, but by who is telling it, when, and why. The narrator is no longer a passive conveyor of events; they are an active participant in meaning-making. And that meaning, inevitably, slips between their fingers — and ours.

The unreliable narrator is the perfect postmodern figure because they mirror us: flawed, interpretive, desperate for coherence but forever haunted by the multiplicity of truth. In giving us voices we can’t rely on, postmodern fiction holds up a mirror to our own interpretive struggles. After all, we too construct narratives — about our lives, our histories, our relationships — and we too bend them, knowingly or not, to survive the chaos.

And just when you think you’ve caught hold of something solid — a fact, a motive, a reliable confession — the narrative reminds you that it’s just another layer in a labyrinth of versions. This is no longer the era of storytelling; it’s the era of story-unmaking, of narrative as palimpsest, where each new version both reveals and erases what came before.

As we step into the next section, we’ll find these voices expanding outward — across nations, cultures, and linguistic borders. The British postmodern moment was never an island. It was a broadcast tower, receiving signals from every corner of the globe, remixing them into novels that were no longer just British, or even national, but boldly and unapologetically global.

British and Global Writers Who Launched the Postmodern Mood

By the time postmodernism was taking shape in Britain, it had already started receiving long-distance postcards from around the world — cryptic, dazzling, multi-lingual messages signed by Borges, Márquez, Calvino, and Rushdie. Unlike earlier literary periods that wore their nationalism like a tailored tweed jacket, postmodernism flung open the wardrobe and stepped into global couture. Its British writers were deeply aware that their narratives were no longer unfolding on an isolated island but inside a tangled web of historical debts, cultural collisions, and linguistic echoes. The world had shrunk, the Empire had fractured, and English literature found itself in conversation with everywhere else.

At the forefront of this shift was Salman Rushdie, whose Midnight’s Children (1981) didn’t just reshape postcolonial fiction — it redefined what postmodern fiction could be. Here was a novel that mixed magic with history, autobiography with absurdity, and national trauma with private memory. Rushdie’s narrator, Saleem Sinai, tells his story with all the reliability of a drunken oracle, and yet it feels truer than fact. Time bends, reality glitches, and the nation itself becomes a character. Rushdie doesn’t hide his influences — he wears them like medals: from Dickensian detail to Bollywood drama, from Eastern mythology to Western literary irony. His language dances — multilingual, mythic, manic — and his postmodernism is not cold and cerebral, but hot with history and spice. Saleem Sinai may be the poster child of magical realism, but he is also the embodiment of metafictional anxiety: he narrates India’s birth while quietly asking whether any story can ever capture a nation.

This literary globe-trotting was echoed by Angela Carter, whose reinventions of fairy tales (The Bloody Chamber, 1979) were as global in tone as they were intimate in desire. Carter’s work deliberately evaded realism — she trafficked in symbol, myth, and erotic metaphor. Her heroines were not passive but defiant, her language lush and dangerous. She tore apart the traditional narratives of womanhood, not through direct attack but through genre-bending alchemy: the gothic met the feminist, the folkloric collided with the psychoanalytic, and the result was electric. Carter did not just retell stories — she unstitched them and rewrote them in blood and silk. In doing so, she joined the global chorus of writers who were no longer content with inherited stories — they demanded the right to interrupt, to subvert, to reinvent.

Alongside them stood the quieter but equally radical presence of Doris Lessing. With The Golden Notebook (1962), Lessing presented not just a novel, but a collage of notebooks — black, red, yellow, and blue — each narrating a different aspect of the protagonist Anna’s life. Politics, motherhood, love, memory, and breakdown are not themes divided by chapters but fractured identities held in parallel narratives. Lessing’s feminism is cerebral but unflinching. Her structure deliberately resists coherence. The notebooks contradict, overlap, echo. What’s real? What’s literary fiction? What’s Anna’s actual life and what’s her novel-in-progress? Lessing, like her peers, refuses to give you one answer. She gives you four versions — and dares you to make peace with all of them.

But it wasn’t just British writers leading this philosophical rebellion. Postmodernism, like the Empire that had once claimed half the globe, now found itself shaped by those very regions it had tried to dominate. Postcolonial literature and postmodern technique became strange bedfellows — and wildly productive ones. Writers from Latin America, Asia, and Africa began blending local mythologies with Western literary experimentation, crafting works that were both rooted and rebellious.

Enter Jorge Luis Borges, the blind librarian of Buenos Aires, who wrote stories like philosophical labyrinths. His narratives (The Library of Babel, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius) were short, dense, and so intertextual they seemed to fold entire worlds inside a paragraph. Borges’s influence on British postmodernism is profound — not only for his themes of infinite regress and textual illusion, but for his example: that a story could be a puzzle, a parody, and a philosophical argument, all at once.

From Italy came Italo Calvino, with If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979), a novel that begins with you trying to read a novel that keeps restarting. Each chapter introduces a new story — none of them finished — as if the book is a prism catching every possible narrative and refusing to settle. The novel is metafiction as performance art: full of traps, illusions, and literary winks. Calvino turned the novel into a gameboard and the reader into a player — confused, enchanted, complicit.

And no global postmodern gathering would be complete without Gabriel García Márquez, who, with One Hundred Years of Solitude, blurred the boundary between the mythical and the mundane. While technically a magical realist, Márquez’s epic is deeply postmodern in spirit — especially in its treatment of time as circular, its unreliable narrative voice, and its refusal to explain its own miracles. His village, Macondo, is a site of eternal return, where generations echo each other and history repeats not as tragedy or farce, but as magical bureaucracy.

Back in Britain, writers like Margaret Drabble and A.S. Byatt were also engaging in subtle postmodern experiments. Drabble, known for her psychological realism, often inserted self-referential moments into otherwise conventional narratives. Byatt, with her Booker Prize-winning Possession (1990), gave us a postmodern historical romance that included forged letters, fake footnotes, and invented poets — a dazzling showcase of literary detective work that reminded readers how often we confuse the authenticity of feeling with the illusion of documentation.

Even genre fiction, long considered the poor cousin of “literary” writing, began to flourish in the postmodern atmosphere. Writers like J.G. Ballard blended science fiction with surreal satire; his Crash (1973) and Empire of the Sun (1984) blurred reality and delusion, trauma and television, memory and apocalypse. Ballard’s language was clinical, detached, but deeply disturbing. He exposed the subconscious of the modern world — and then watched it self-destruct with quiet fascination.

These writers — British and global — were not simply sharing techniques. They were united in their rejection of singular meaning, in their fascination with myth, memory, multiplicity. They treated language as suspect, narration as performative, genre as flexible, and the past as something that could be rewritten from a thousand vantage points. In their hands, literature became less a form of expression and more a site of interrogation — a space where history, identity, and meaning were tested, stretched, and sometimes playfully exploded.

What binds them isn’t geography, or even ideology. It’s the postmodern instinct to say: “The story you know isn’t the only story. And maybe it’s not even the right one.”

In the next section, we step into the theatre — but not the kind where curtains rise and fall in polite rhythm. Instead, we’ll meet playwrights who broke the fourth wall, forgot the plot, rewrote the actors mid-play, and asked whether any of this was real to begin with. It’s time to enter the absurd, ironic, brilliantly disoriented world of postmodern drama.

Theatre of the Absurd and Meta-Drama

The postmodern stage is not built on certainty — it’s built on sand, mirrors, and jokes whispered into the void. Gone are the carefully crafted five-act structures, the tidy conflicts and moral resolutions of Shakespearean or classical drama. Instead, postmodern theatre arrives wearing the mask of confusion, muttering about existential dread, and then breaking character to discuss the meaninglessness of the production itself. This is not a play you watch; it’s a play that watches you — and sometimes asks whether either of you are real.

Though often seen as separate from literary fiction, postmodern drama was equally invested in breaking the fourth wall — and then mocking the very idea of walls, or stages, or audiences. If traditional theatre asks you to suspend disbelief, postmodern theatre snatches disbelief from your hands, shreds it, and then hands it back as confetti. At the heart of this revolution is the Theatre of the Absurd — a movement born in the ruins of World War II, yet flourishing fully in the postmodern mindset.

The phrase itself was popularised by critic Martin Esslin, who applied it to playwrights like Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Jean Genet, and Eugène Ionesco. These dramatists didn’t just question meaning — they built entire plays around its total absence. But unlike Modernism, which mourned that loss, postmodern drama learned to laugh at the void. It treated confusion as a form of liberation.

No figure embodies this more than Samuel Beckett, whose minimalist masterpiece Waiting for Godot (1953) remains a cornerstone of postmodern dramatic absurdity. In it, two characters — Vladimir and Estragon — wait endlessly for someone named Godot, who never arrives. They fill the time with repetitive dialogue, slapstick confusion, existential questions, and a bizarre sense of theatrical stillness. Nothing happens — twice. Yet the play remains a haunting reflection of human desperation, repetition, and absurd hope. It is a meta-commentary on theatre itself, with characters who know they’re in a loop, know they’re being watched, and yet can’t escape the performance.

Beckett’s later works go even further into fragmentation. In Krapp’s Last Tape, an old man listens to recordings of his younger self and reacts not with nostalgia but with confusion, bitterness, and detachment. The past isn’t just inaccessible — it’s performatively foreign. Memory becomes a performance, identity a series of recorded footnotes, and the stage a place where nothing lines up except the silence.

If Beckett was the poet of emptiness, then Harold Pinter was the master of menace. His plays — The Birthday Party, The Homecoming, The Dumb Waiter — present ordinary situations laced with terrifying ambiguity. Characters speak in pauses, non-sequiturs, and unfinished thoughts. But what lurks beneath is dread — psychological, political, linguistic. Pinter’s famous “Pinter Pause” isn’t just silence; it’s the weight of what’s unsaid, a gap where truth might’ve once lived but now echoes coldly.

What makes Pinter profoundly postmodern is his refusal to provide context. Who are these people? Why are they threatened? Who’s in control? Is anyone in control? He offers no exposition, no resolution, no moral compass. The play ends, and you’re left mid-thought, mid-panic, mid-theory. In postmodern theatre, the audience is not led to understanding — they’re abandoned in the foyer of their own discomfort.

The self-awareness of theatre also becomes a central device. Enter Tom Stoppard, the king of meta-drama, who doesn’t just break the fourth wall — he waltzes through it in a bowler hat, quoting Shakespeare and quantum physics. In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), he takes two minor characters from Hamlet and turns them into postmodern protagonists. They stumble through a world they don’t understand, trapped in a narrative written by someone else, quoting lines they don’t mean, and dying in a plot they can’t control. Sound familiar? That’s because postmodernism treats life itself as scripted, unreliable, and absurdly theatrical.

Stoppard’s characters frequently discuss the nature of theatre while being in a play. One flips a coin ninety times and it lands heads each time — a statistical anomaly that becomes a metaphor for narrative predestination. The joke lands, but underneath it lies a creeping existential terror. Are we making choices? Or are we just actors in someone else’s script, waiting for the next cue?

Other playwrights followed suit. Caryl Churchill blended surrealism with sharp political satire. Her Cloud Nine (1979) collapses time, swaps gender roles, and performs colonial critique by deliberately exposing the mechanics of performance. Characters change actors between acts. Identity becomes drag. The entire idea of “stable character” is queered, questioned, and re-costumed mid-scene.

Even comedy was no escape. British farces like Michael Frayn’s Noises Off (1982) made chaos their content. It’s a play within a play — about a failing play — where the audience watches the collapse both front-stage and backstage. Scripts are forgotten, props misplaced, relationships implode. What begins as farce quickly becomes meta-theatrical tragedy, where the performance’s failure becomes the play’s success.

What all of these plays share is not a theme, or a message, or even a structure. What they share is a mood: of uncertainty, of playful chaos, of suspicion toward language, identity, and authority. Postmodern drama doesn’t want to entertain in the traditional sense. It wants to disturb, disorient, provoke — and yes, sometimes tickle — all while whispering that none of this is real, and neither are you.

This rejection of dramatic convention is, paradoxically, what makes postmodern theatre so theatrically powerful. It reclaims the stage not as a space of illusion but as a site of confrontation. It forces the audience to confront themselves — not as passive viewers but as co-authors in meaning-making. The play no longer pretends to be life. It turns to you and asks: Which parts of your life are you merely performing?

In the next section, the drama continues — but offstage. We will now return to the novel, where capitalism, consumerism, and media have become new gods. The postmodern writer, ever vigilant, turns their pen into a scalpel and begins dissecting the language of advertising, politics, and money — revealing how deeply our stories have been sold to us.

The Language of the Marketplace — Capitalism, Media, and Control

If the earlier sections of postmodernism played with myth, language, and identity, this one flips the mirror outward. Because somewhere between the rise of television and the fall of ideology, literature realized it was no longer the only storyteller in town. The advertiser had a better tagline, the politician a more viral slogan, and the multinational brand a bigger budget. And so, postmodern literature turned to face its newest antagonist — not the tragic hero or the villainous state, but the marketplace itself.

In this postmodern landscape, language is no longer a sacred tool of poetic beauty — it is a commodity. Words are bought, sold, packaged, repurposed, and broadcast. Identity is curated like a brand. Meaning is whatever sells. And so literature, increasingly aware of its marginal status in a media-saturated world, begins to parody the very systems that threaten to erase it.

This is where we find novels that sound like shopping malls, characters who speak in jingles, and narratives that mimic marketing pitches. The language of the marketplace becomes the style of the novel, and postmodern writers, always delighted by irony, adopt the very idioms they seek to dismantle.

One of the sharpest examples of this is Martin Amis and his blistering novel Money: A Suicide Note (1984). Here, the narrator John Self — a name chosen with all the subtlety of a neon punchline — is a grotesque embodiment of 1980s consumerism: addicted to fast food, porn, alcohol, and advertising. He is loud, vulgar, and utterly hypnotised by money. But Amis doesn’t preach. He doesn’t moralize. Instead, he lets the language of capitalism self-destruct. John Self is both product and parody — a man whose inner life is so overrun by commercial clutter that he no longer exists outside of what he consumes.

The narrative voice is laced with slogans, pop-culture allusions, sexist magazine chatter, and self-help detritus. It’s a novel that sounds like it’s been binge-watching TV and reading receipts — and that’s precisely the point. Amis understands that to critique a media-obsessed world, you must write in its dialect — and then slowly turn that dialect against itself.

Elsewhere, in works like Angela Carter’s Wise Children (1991), we see performance culture taken to surreal, theatrical heights. Narrated by Dora Chance, a former music-hall star, the novel is saturated with the language of entertainment, celebrity, and illusion. Shakespearean references blend with soap opera tone; tabloid sensationalism sits comfortably beside literary wit. Carter paints a world in which identity, family, and even art are all performances for sale — and the stage is never empty.

Postmodern literature in this phase begins to echo the techniques of advertising — repetition, catchphrases, false promises, emotional manipulation. But instead of trying to sell you something, these novels try to show you how you are always being sold to. The boundaries between sincerity and irony collapse. A character might declare love in the language of a perfume ad, or describe their breakdown using wellness jargon. The body is a billboard. The soul a subscription service.

This cultural infiltration extends into the structure of the novels themselves. Works like Alasdair Gray’s Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981) include indexes, appendices, typographical experiments, and metafictional asides that mimic corporate documentation — annual reports, health warnings, instruction manuals. Gray doesn’t just critique bureaucratic language — he repurposes it. In doing so, he reminds us that in modern life, even dystopia comes with a user’s guide.

Meanwhile, J.G. Ballard gives us novels like High-Rise (1975), where consumer convenience becomes societal decay. In this tower of affluence and modernity, residents descend into tribal warfare, hoarding wine and designer furniture while tearing down the very system that enabled their luxury. Ballard’s vision is bleak, surgical, and eerily prophetic — the future is marketed as convenience, but delivered as cultural collapse. The prose is stripped, metallic, antiseptic. It doesn’t comfort. It reports. And what it reports is a world dehumanized by its own technological aspirations.

In another arena, postmodern poetry joins the conversation — or rather, joins the commercial break. Poets like Tony Harrison and Simon Armitage blend the colloquial, the political, and the commodified, creating verse that sounds like it could be overheard in a supermarket aisle or scribbled into a corporate newsletter. The poetic voice has moved from the mountaintop to the metro station — and it’s wearing ironic trainers.

At the heart of this entire movement is a suspicion of linguistic authority. In a world dominated by media, politics, and PR, who owns the words? Who controls the narrative? Postmodern literature doesn’t just ask these questions — it echoes the noise of their answers. It creates characters who speak in press release syntax, who quote television hosts mid-confession, who shape their very personalities through curated media consumption. These are people whose minds are brand-saturated. Their inner monologue is sponsored.

And yet, the tone is not always despairing. Postmodernism often laughs. It performs its own absurdity. It quotes the brand slogan and adds a punchline. It lets the reader in on the joke — a wink that says, “Yes, this too is performance. But at least we’re aware of the costume.”

This final maneuver — this turning of the capitalist language into a literary boomerang — is perhaps the greatest irony of all. Postmodern literature enters the marketplace not to sell, but to satirize the act of selling itself. It mimics the media not to flatter it, but to expose the layers beneath its glossy surface. In this way, even the most jaded, ironic voice becomes a whisper of resistance.

As we close this section, we stand at the threshold of the postmodern expansion. Ahead lies the second phase — the late 1980s to 2000 — where globalization, digital media, and postcolonial complexity redefine the very idea of literature. But here, at the end of Part 1, we pause in the glittering chaos of consumer culture, watching literature shout into the marketplace — and hearing, for a moment, that the echo still carries poetry.

They questioned truth, parodied tradition, and left us footnoting footnotes.

The Postmodernists didn’t just break the fourth wall — they made sure it never existed.

From Auden’s elegiac turns to Beckett’s minimalist voids and Carter’s carnival of subversions, we crossed a literary terrain where structure collapsed and meaning shrugged.

But perhaps that’s the beauty of it.

When the grand narratives give way, we begin to write our own.

Scroll folded, irony intact, metafictional quill returned to drawer.

The Professors nod, not in agreement — but in delightful poststructural uncertainty.

Signed,

The Literary Professor

From the Professors’ Desk

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance