Literature between War and Whisper: The Final Phase of Modernism (1939–1959)

From The Professor's Desk

When literature walks through the fire, it seldom comes out unburnt.

The years 1939 to the late 1950s represent not a neat ending, but a scorched continuum of modernism — disillusioned by one war, scarred by another, and finally entrapped in a new kind of silence: that of the absurd, the alienated, and the atomic. If the early modernists had questioned the past, these later voices watched the present unravel. Civilization itself was on trial — and literature became both witness and elegy.

When the world reeled from the first war, it wrote poetry. When it survived the second, it lost its voice—only to find it again in fiction, drama, and satire sharpened by ash and echo. The final stretch of Modernism wasn’t a surrender—it was a reconfiguration. While bombs fell and borders redrew, the written word bore witness, asked questions, and crafted quiet revolutions. The years from 1939 to the late 1950s represent the weary grandeur of Modernism’s last stand—where prose was brittle, poetry was introspective, and every sentence remembered a scream.

Shadows over Civilisation — The Literary Mood of 1939

The outbreak of the Second World War was not merely a geopolitical rupture; it was, in literary consciousness, the crack in the human psyche. If the First World War had disillusioned the Romantic ideal of honour in conflict, the Second World War dismantled any lingering belief in the moral coherence of civilisation. The literary output of the 1940s bears the bruises of blitzed cities, concentration camps, displacement, and a gnawing realisation: that man’s capacity for horror had grown more mechanised, more rational, and more intimate.

The Modernist project, which once celebrated the fragmentation of form and the subjectivity of truth, now found itself in ethical crisis. Was artistic experimentation still possible in a world that had turned Auschwitz into a historical reality and Hiroshima into an irreversible metaphor? Writers struggled to balance the aesthetic with the moral, to speak of beauty when language itself seemed to stammer.

One hears this literary stammer in the verse of W.H. Auden, who, having moved to America, famously wrote September 1, 1939 in a New York bar as the war broke. The poem ends not with grandiosity, but with intimacy and humility:

We must love one another or die.

Though Auden later disavowed that line, it remained etched in the literary psyche of the period — a line caught between Modernist detachment and a desperate moral imperative.

In parallel, Stephen Spender, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Louis MacNeice — the so-called “Auden Group” — wrestled with how to write verse that was socially urgent yet aesthetically modern. Their poems were no longer concerned with myths or the subconscious alone; they were embedded in air raids, political manifestos, and the soot of urban survival.

Meanwhile, prose turned even more inward, yet ironically more universal. Virginia Woolf’s final years, shadowed by war and personal despair, culminated in her poignant suicide in 1941. Her last novel Between the Acts, posthumously published, reads as a meditation on art’s futility and transcendence during wartime — a village pageant staged even as the world collapses around it.

If earlier Modernism fractured narrative to reflect a fractured consciousness, wartime Modernism offered no such luxury. The question now was not ‘how to write’ but ‘why write at all?’ In the face of genocide, totalitarianism, and global disarray, literature was not retreating into escapism but interrogating its very legitimacy.

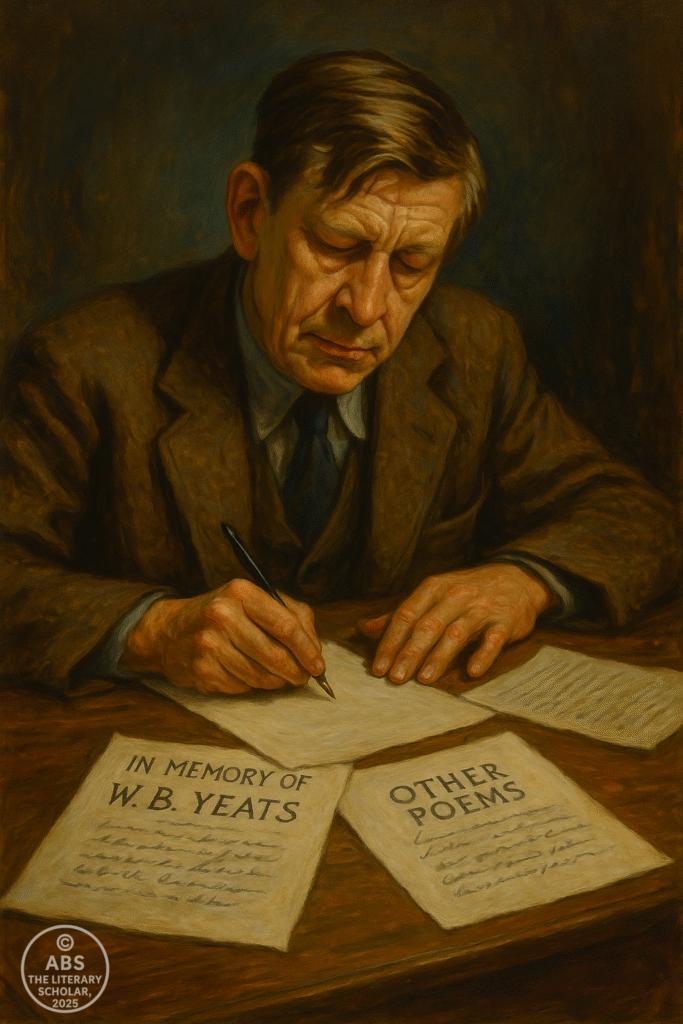

W.H. Auden and the Ethics of Witnessing

In a century bruised by mechanised warfare and ideological extremism, Wystan Hugh Auden emerged not only as the voice of an age but as its moral barometer. A poet who migrated physically (from England to America) and spiritually (from Marxism to Christianity), Auden carried the Modernist torch into darker decades with a tone more confessional than triumphant, more searching than declarative.

He was, in many ways, the reluctant prophet of catastrophe.

“The lights must never go out,

The music must always play…”

— September 1, 1939

These lines, written as Europe trembled on the brink, encapsulated the quiet terror of a society pretending normalcy in a collapsing world. Unlike T.S. Eliot’s fragmented mysticism or Yeats’s mythic grandiosity, Auden’s voice was more intimate, more tired. His poetry refused the consolation of final answers — yet it also refused to turn away.

Auden’s “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” (1939) became not only an elegy for a man, but an elegy for a poetic worldview. The modern poet, Auden insisted, “must be more responsible,” must face not only aesthetic dilemmas but moral ones:

“Poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making…”

These lines, paradoxically resigned and resolute, reflect Auden’s internal war: between the power of poetry and its impotence in preventing actual war. He does not idealise Yeats but reinvents the poet’s role — no longer as bard or oracle, but as a fallible recorder of human contradictions.

In the post-war years, Auden’s shift to a more Christian framework shaped works like For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio and The Age of Anxiety, the latter of which lent its title to an entire era of literary despair. “The Age of Anxiety” was not just a phrase — it was a state of being. With its dense allegorical structure and psychological tone, the poem dramatized spiritual emptiness in a material world, where the self was increasingly fragmented by politics, advertising, and war trauma.

Yet Auden never abandoned craft. He remained a technician — of meter, form, and rhyme — even as the content of his verse grew more metaphysical. He blended psychoanalysis, theology, classical references, and radio news bulletins into a poetic voice that felt both grounded and disoriented.

In many ways, Auden was the emotional conscience of late Modernism — a poet aware that words could never stop tanks, but also that silence would be complicit.

He stands not as a torchbearer, but as a man holding a flickering candle — illuminating, however briefly, the darkness that made such poetry necessary.

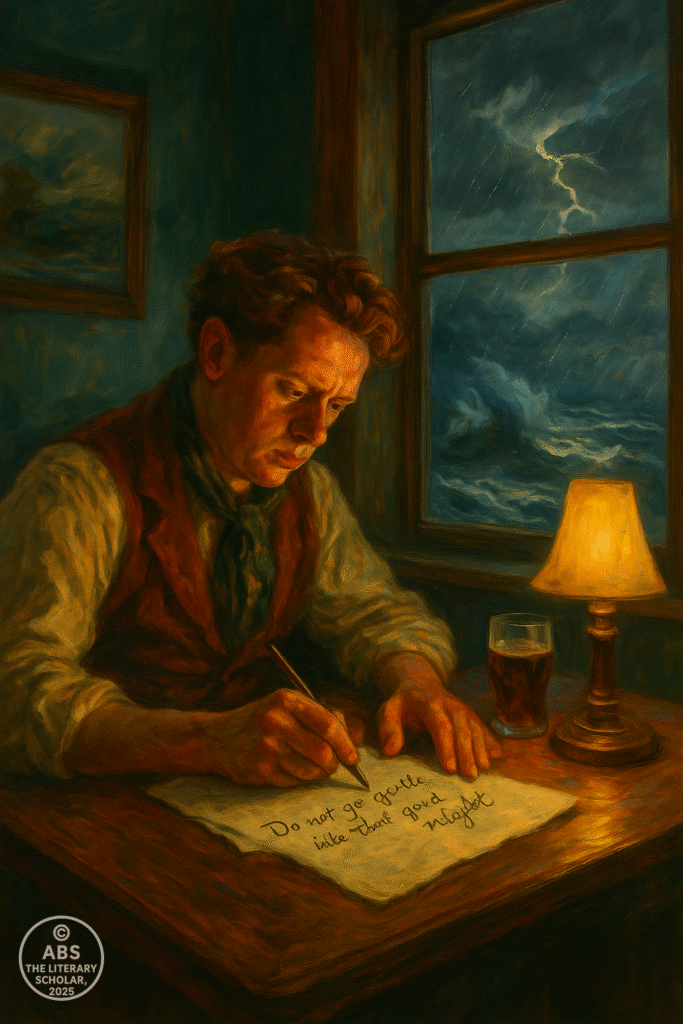

Dylan Thomas — Raging Against the Dimming of Light

If Auden whispered about doubt with surgical precision, Dylan Thomas howled it through the storm. Born in Swansea, Wales, Thomas was Modernism’s rogue — a poet who never quite fit the literary molds of Eliot’s fragmentation or Auden’s ethics, yet carved his own thunderous path through the century’s shadows.

He was no theorist. He was a poetic force of nature, more likely to drink metaphors than dissect them. And yet, through visceral language and biblical cadence, Thomas injected emotional excess into an era defined by psychological restraint.

His most iconic command —

“Do not go gentle into that good night” —

was not just a plea to a dying father. It was a primal scream hurled at death, time, silence, and entropy. In a century obsessed with decline, Thomas did not document it — he wrestled it with breath and vowel.

Thomas’s poems, such as “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”, “Fern Hill”, and “Poem in October”, feel less like literature and more like weather systems. His use of villanelle, refrains, and sonorous consonants was not just aesthetic — it was elemental. Here was a poet who turned grief into a chant and memory into gospel.

Where Eliot dissected the fractured mind, Thomas glorified its fever.

“The force that through the green fuse drives the flower / Drives my green age…”

— from The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower

In these lines, the self becomes indistinguishable from nature — not in peaceful union, but in violent propulsion. For Thomas, life was not a philosophical problem — it was a flesh-and-blood explosion, and his poetry was an attempt to catch the splinters before they vanished.

Yet behind the myth of the Welsh drunkard-poet lay an artist meticulously attuned to rhythm, myth, and linguistic ancestry. He was not careless — he was just ferociously intuitive, choosing words the way a storm chooses trees.

His influence, though short-lived due to his early death at 39, left a reverberating tremor through both American Beat poetry and British confessional verse. He showed that Modernism could still feel — wildly, bodily, and unreasonably.

Where Auden intellectualised the loss of faith, Thomas screamed at the heavens and refused to let the sky go quietly.

He did not edit reality. He howled it into eternity.

Existential Drama — Beckett, Pinter, and the Theatre of Emptiness

As bombs fell over Europe and ideologies cracked open like skulls, literature began to ask a strange, terrifying question:

“What if there’s nothing left to say — and no one listening anyway?”

Enter Samuel Beckett, the reluctant messiah of absurdity, whose Waiting for Godot (1953) became the most paradoxically powerful play about powerlessness. In a barren, unnamed landscape — neither past nor future, neither here nor there — two tramps wait endlessly for a figure who never arrives.

Godot never comes.

The meaning never lands.

And still, they wait.

Beckett’s gift was not simply creating a play. He stripped drama of plot, climax, character arcs, and even resolution — and exposed the skeletal remains of existence itself. In his world, words don’t clarify — they delay. Time does not pass — it loops, limps, and limbos.

“They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

— Waiting for Godot

The line doesn’t just sum up the play — it sums up the century.

In the same existential hall of mirrors, Harold Pinter sharpened silence into a dagger. His comedies of menace — particularly The Birthday Party (1957) and The Caretaker (1959) — took banal domestic scenes and infused them with a creeping, wordless terror. Conversations broke down into pauses, evasions, and unspoken threats, where language was less about meaning and more about control.

Where Beckett showed how we endure the void, Pinter showed how we weaponize the void.

Both dramatists reflected the post-Holocaust consciousness — where the theatre was no longer a stage of human nobility or catharsis, but an arena of absurd repetition, shrinking options, and nervous jokes. Nothing was sacred. Not God, not meaning, not even chairs. (Especially not chairs — ask Endgame.)

And yet, in this very emptiness, something miraculous occurred: theatre became profound again.

Because when everything is hollowed out, even a whisper becomes thunder.

Beckett and Pinter did not invent existentialism, but they breathed it, staged it, and made us laugh in despair.

“Nothing to be done.”

And yet, they wrote everything.

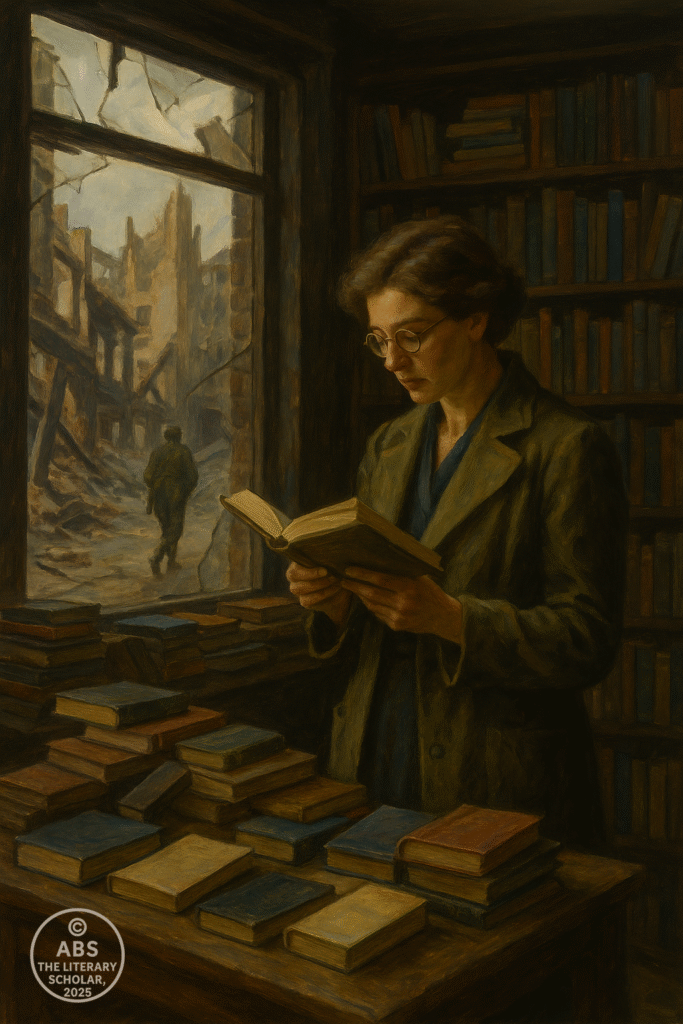

Poetry After the Blitz — The Struggle to Speak Again

When the bombs stopped falling and the silence returned, it wasn’t peace that echoed — it was shock.

The war had ended, but its impact had perforated the poetic soul. Modernist fragmentation was no longer a style — it was the world’s new default. Poets in the mid-20th century, standing amid the charred ruins of certainty, now wrestled not just with form and feeling, but with language itself.

Could poetry still say anything meaningful? Or had the age of irony permanently drowned the lyric voice?

It is in this fragile cultural aftermath that we meet Dylan Thomas, a bard from Wales who sang like a prophet in a pub. In an era of disillusionment, his poetry still shimmered with mysticism, rhythm, and rebellion.

“Do not go gentle into that good night…”

“Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Here was a man who refused to surrender to silence. Thomas, in his villanelles and hymnal laments, gave us intoxicated rage at death and musical metaphysics. He was more than a post-war poet — he was a ghost lit by ale and vision, clawing meaning from chaos.

And then there was Philip Larkin, who brought poetry back to the daily, the drab, the dreadful. While Thomas sang of eternity, Larkin coughed up existence as slowly suffocating routine.

“They fuck you up, your mum and dad…”

“What will survive of us is love.”

He wasn’t mystical, and he didn’t rage — he muttered. In libraries and small towns, Larkin composed the anti-epic: quiet elegies for a culture slowly slipping into suburbia. His genius was in naming what we do not name — boredom, loneliness, emotional parsimony.

Where Dylan Thomas howled, Larkin sighed. But both — in vastly different ways — charted the post-Blitz psyche.

And yet poetry didn’t live only in Britain. In America, post-war poets were also staging their revolt — but we’ll give them a full spotlight soon. For now, in the transatlantic tremors of this period, we can also sense the gradual decline of Modernism’s high art snobbery, replaced by a poetry that dared to be ugly, honest, brief — and human.

A new literary economy was emerging — where every word had to pay rent, and metaphor was no longer decoration, but survival.

In the charred ruins of civilization, poetry did not rebuild the cathedral —

but it picked up the stained glass pieces,

held them to the light,

and whispered,

“Look… it still shines.”

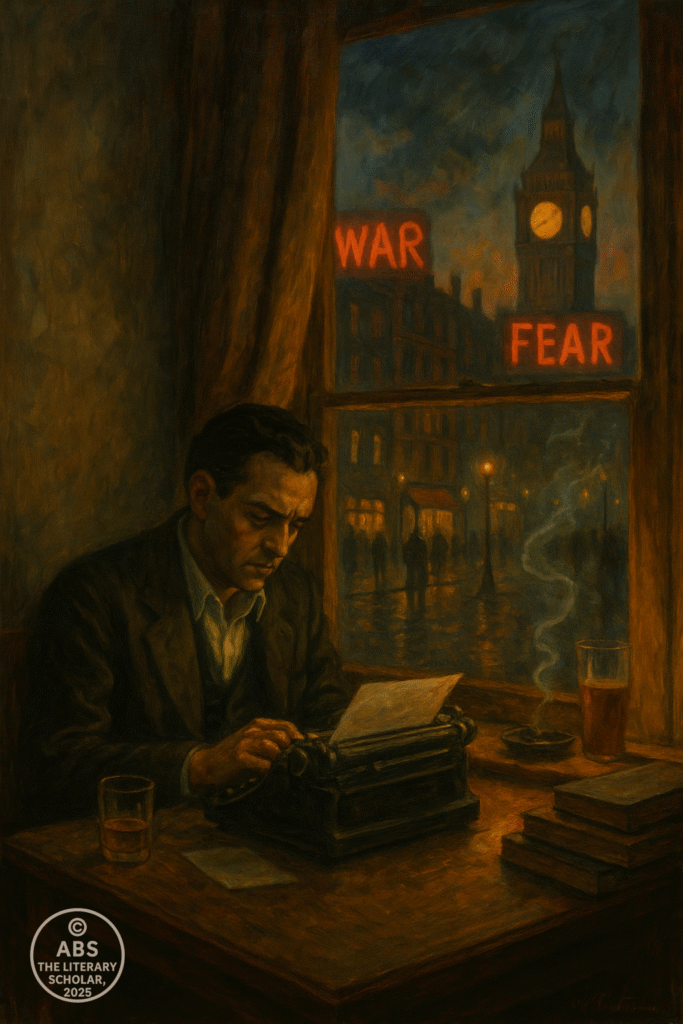

Prose Between Ruins — Novels of Reflection, Resistance, and Rebirth

While poetry gasped for breath after the bombs, fiction had no such luxury — it marched on, sometimes limping, sometimes charging, but always compelled to record, reflect, resist.

The post-war novel was born not in triumph, but in tension. It didn’t sing of glory; it unpacked the suitcase of survival.

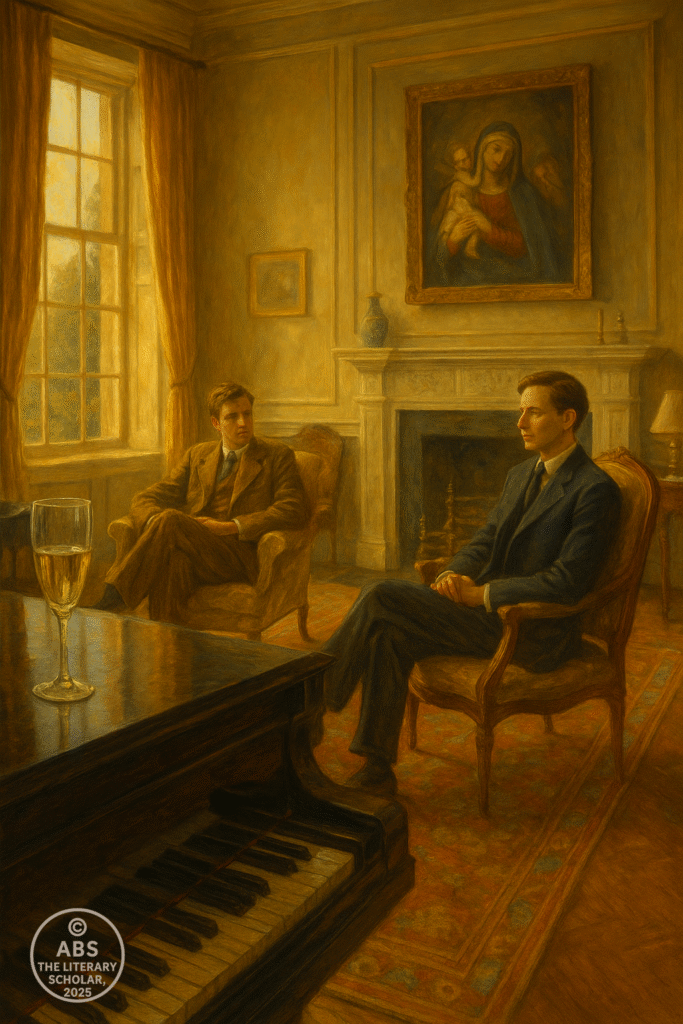

Enter Graham Greene, the priest of paradox. Half thriller-writer, half theologian, Greene wrote of betrayal, guilt, and the haunted corridors of the human soul. In The Heart of the Matter and The End of the Affair, faith and espionage dance uncomfortably — God is everywhere, even in adultery, even in despair.

Greene’s fiction did not seek to comfort — it sought to confess.

Meanwhile, Evelyn Waugh, ever the master of satire, offered Brideshead Revisited, a baroque lament for lost aristocracy, spiritual hunger, and the fragile thread of Catholic faith in a war-shaken world. Though once a roaring cynic, Waugh here became a nostalgic mourner, sipping champagne with ghosts.

And then came the voice of absolute survival — Primo Levi, in If This Is a Man. Here, fiction was not stylized, but stripped — narrative without embellishment, prose as witness. The camps had silenced many, but Levi refused to let horror become abstraction.

“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men…”

As the Holocaust seeped into the literature of Europe, the novel became an archive of moral aftermath. Writers were no longer inventing characters — they were confronting shattered selves.

In France, Albert Camus‘s The Plague gave us more than a literal epidemic — it became an allegory of fascism, of helplessness, of absurd resistance. The novel’s doctor does not cure, but endures. Like Camus himself, the novel does not give answers, only stares into the void and says — keep walking.

Across the Channel, George Orwell had already warned us — in 1945’s Animal Farm and 1949’s 1984. These were not just satires or dystopias. They were cultural detonations. Orwell’s prose was the scalpel and the sledgehammer, slicing propaganda and smashing apathy.

“If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”

What united these writers was not style or nation or genre — it was urgency.

They didn’t write to entertain — they wrote to remind, reveal, remember.

Their sentences smelled of ink and ash. Their plots wove through wounds and warning signs. Post-war prose was not passive; it was a long, hard stare in the mirror, and often, the image staring back was not heroic, but hollow-eyed.

And yet, through all this bleakness, literature did not collapse.

It recalibrated.

It stopped pretending the world was fair and began asking —

how do we live in a world that isn’t?

Theatre of Shadows — Post-War Drama and the Absurd Stage

The curtain rose, but the old scripts no longer made sense.

After Auschwitz, after Hiroshima, after Dresden’s firestorms and Nuremberg’s verdicts — theatre was not the same. The drawing-room comedies of the pre-war stage now seemed quaint, almost grotesque. Laughter had cracked. Language had stuttered. Meaning itself had begun to unravel.

What emerged was a theatre of silence, absurdity, and existential dread.

First to truly seize this stage was Samuel Beckett, whose Waiting for Godot (1953) didn’t just confuse audiences — it redefined the very act of watching and performing. Two men, Didi and Gogo, wait for someone who never arrives. Nothing happens. Repeatedly. And yet, in that nothingness, a profound truth emerges:

“Nothing to be done.”

This was not nihilism for its own sake. This was a philosophical howl—a play where pauses mattered more than plot, and gestures replaced action. Beckett had seen war, served in the Resistance, and lost faith in narrative consolation. In Endgame, Krapp’s Last Tape, and his minimalist prose, he turned theatre into a metaphysical excavation.

Meanwhile, in France, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus staged their philosophical dilemmas. Sartre’s No Exit popularized the chilling dictum:

“Hell is other people.”

The post-war play was now a space of confinement, confrontation, and collapsing identity. Camus’ Caligula and The Just Assassins offered rebellions that were never truly heroic — but always human. Guilt, death, and freedom echoed louder than applause.

Even in Britain, a different disillusionment brewed. T.S. Eliot, though better known for his poetry, staged The Cocktail Party (1949) and other verse dramas that exposed spiritual sterility beneath polite surfaces. Eliot’s dramas, influenced by his Anglican conversion, brought metaphysical tremors into drawing rooms and parlours.

But the post-war British theatre would soon prepare for a sharper rupture.

By the late 1950s, the seeds of social anger had been sown. The war had ended, but the class divides, the economic frustration, and the cultural disillusionment lingered. The Angry Young Men were coming — but they belong to the next section.

For now, the theatre remained dimly lit, stage floors bare, scripts full of stammers and sighs. It was a space where logic failed, where humanity stood absurd and aching beneath an indifferent cosmos.

Post-war drama did not seek catharsis. It offered confrontation.

This was theatre as existential echo chamber, where what wasn’t said — hurt more than what was.

The Angry Young Men — Rebellion in Rehearsal, Protest in Prose

By the late 1950s, British literature had traded in its tweeds for torn jackets, its cocktails for cigarettes, and its polite conversation for a raw, rumbling dissatisfaction. The Empire was crumbling. The war was over, but not gone. And somewhere in a Midlands bedsit, a working-class intellectual was shouting at the wallpaper.

Enter the Angry Young Men — a loosely grouped movement of playwrights, novelists, and commentators who shared no manifesto, no single philosophy, and no patience for the literary status quo.

They were angry — and not quietly so.

The poster child of this rebellion was John Osborne, whose 1956 play Look Back in Anger detonated like a kettle finally boiling over. Jimmy Porter, the central character, didn’t merely complain — he raged. Against the establishment. Against class hypocrisy. Against emotional inertia. His anger wasn’t elegant. It was necessary.

“There aren’t any good, brave causes left.”

With those words, British drama was reborn — grittier, grimmer, and grounded in real lives, not mythic ideals.

This shift wasn’t confined to the stage. It spilled into novels.

Kingsley Amis brought it into fiction with Lucky Jim (1954), a savage and hilarious satire of academic pretension and social climbing. His protagonist, Jim Dixon, was no hero, but he was unmistakably modern: weary, cynical, and allergic to pomposity. The novel was a war cry against upper-middle-class smugness. It sneered — and that sneer struck home.

Alongside Amis and Osborne stood Alan Sillitoe with Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and John Braine with Room at the Top — both probing the lives of young men trying to escape class ceilings, only to find the air equally suffocating on higher floors.

What united these writers was not ideology, but emotional honesty. They weren’t writing about kings, bishops, or highbrow existential dilemmas. They were writing about tea-stained despair, grimy ambition, and the inability to say what one really felt.

This wasn’t high Modernism. It was mud-and-blood Realism, stripped of poetic distance. And it spoke to a generation tired of repression — literary and otherwise.

The Angry Young Men were not revolutionaries in the streets. They were quiet arsonists, burning down the genteel facades of post-war British literature from within.

But by the time the 1960s dawned — louder, freer, and drenched in colour — even the angry started to sound conventional.

Still, in their brief, brilliant blaze, these writers showed literature could be as immediate as a shout, as unpolished as a pub brawl, and as deeply felt as a love letter never posted.

Their fury was their fiction.

The End of Modernism

With this, we close the long, spiraling arc of Modernism — a literary epoch that broke the mirror of Victorian certainty and wrote with its shattered fragments. From the war-torn cries of trench poets to the echoing soliloquies of Woolf’s rooms, from Eliot’s intellectual despair to Beckett’s minimal silences, the modern mind turned inward — questioning time, self, language, and the very shape of meaning.

Modernism didn’t merely innovate. It interrogated.

It tore down structures only to replace them with the poetry of ruin.

It shattered chronology to reassemble consciousness.

And it offered not answers, but authenticity — raw, wounded, and brave.

Now, as we prepare to cross into the next era — the realm of Postmodernism, where meaning splinters further and theory redefines the author and the text — we carry with us the intellectual daring of Modernist pioneers.

Their legacy is not just in their books, but in how we read, write, and rethink everything that came before and after.

This, then, is not an ending.

Only the last still page of a restless chapter.

Signed,

The Professor

The Professor’s Desk

Where literary history is not just studied, but remembered.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance