From The Professor's Desk

The Great War did not only kill men. It mutilated meaning.

The year was 1914. The sun never set on the British Empire, and across Europe, proud nations paraded their flags to the rhythms of certainty and superiority. It was a world—arrogant, armored, and unsuspecting—marching straight into its own unmaking. In salons and streets alike, few could foresee that this summer would pull the pin on modern civilization, scattering its artistic confidence, its moral assumptions, and its literary voice.

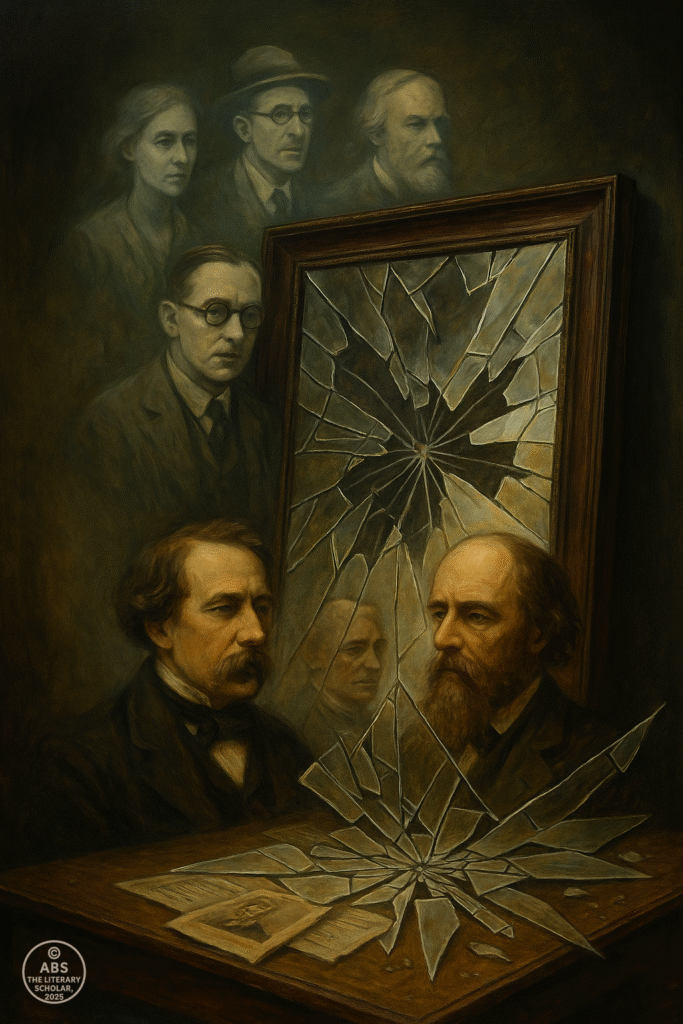

The First World War did not merely redraw maps—it shattered meaning.

For centuries, literature had functioned with an implicit contract: that the world could be made sense of. That experience, even pain, could be organized into plot, expressed in verse, and wrapped in the logic of narrative. But the war that unfolded in the muddy trenches of Ypres and the frozen fields of the Somme defied such structure. It deformed the very idea of form.

And thus, Modernism was no longer just a whisper. It was now a cracked mirror, held up to a world unraveling.

Before the first shots were fired, poets like Rupert Brooke still believed in noble sacrifice.

“If I should die, think only this of me…”

—his sonnet declared, with patriotic serenity, as if the grave were a quiet garden.

But the trenches offered no such serenity. The war was not a field of glory. It was a meat grinder of youth, soaked in gas and mud and silence. It was where idealism went to bleed.

What followed was not a change in language, but a crisis in language.

How does one write a sonnet after watching a friend choke on mustard gas?

Words began to falter. They broke open. They shrieked. They lay in fragments.

Poets like Wilfred Owen did not merely describe war—they relived its nightmares on the page:

“Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling…”

—here, punctuation and panic become indistinguishable.

Where Brooke’s death was poetic, Owen’s was punctured by pity, fury, and the final betrayal of empire:

“Dulce et decorum est / Pro patria mori”

—the old lie, etched in Latin, now vomited back in irony.

Then came Siegfried Sassoon, who did not mourn from the margins but raged from the middle.

A soldier-poet with medals on his chest and sardonic bombs in his pen, he named names:

“He’s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack, / As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack…”

The General, like so many, safe behind lines.

The war did not kill literature. It compelled it to mutate.

And mutate it did—into stuttering prose, clipped poems, narratives interrupted by shellfire.

Realism bent, and expressionism surged. Diaries became documents. Letters turned into elegies.

The old gods were gone. And God, as Nietzsche warned, was dead long before the trenches proved it.

Modernist literature and World War I

The Guns of August: The World Walks into Fire

The year 1914 did not begin with war. It began with optimism — festivals, innovations, and the arrogant stability of European empires. But optimism is often the prelude to catastrophe. By August, the entire continent had combusted into flames. The First World War — not yet called the First, for they didn’t know there would be a second — arrived like an avalanche no one could stop.

What happened was not a war in the classical sense, with battlefields and boundaries. It was a collapse of civilization into mud, metal, and madness. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was only the trigger. The real causes lay deeper: an empire’s insecurity, another’s ambition, military mobilizations ticking like time bombs, and leaders blindfolded by pride. Europe, armed to the teeth and drunk on power, stumbled into the abyss.

And with it fell the old world — the Victorian confidence, the Edwardian calm, the very belief in progress and order. The war destroyed more than lives. It shattered language, meaning, and the human spirit.

The war was mechanized horror. Barbed wire, machine guns, trenches stretching across continents, gas attacks that melted lungs — these were not the weapons of chivalry. They were the tools of mass production and mass destruction. “The old lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” wrote Wilfred Owen, bitterly dismantling the romantic myth of noble sacrifice.

Men who had read Latin odes and English sonnets found themselves choking in trenches. Mud filled their boots. Shells shattered their eardrums. Rats ate their dead. There was no room for heroism — only endurance. And when words returned, they came back disfigured.

The language of war poetry changed drastically. Gone were the grand stanzas and ornate rhetoric of Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade.” In their place came truncated lines, fragmented metaphors, bleeding syntax. Sassoon’s sarcasm, Owen’s haunted verses, and Rosenberg’s gritty realism carved a new poetic vocabulary — not to glorify war, but to accuse it.

“What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.”

(Wilfred Owen)

In these lines, even the structure breaks — enjambments like shellfire, punctuation like gasps. Form follows trauma. The war changed not only what poets said, but how they could say it.

Even prose was not spared. Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End and Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier dared to probe the psychological devastation of returning veterans. Consciousness itself had become unreliable. Shell shock, memory lapses, emotional numbness — these now shaped narrative form.

The war didn’t kill fiction; it tore it open. Realism seemed insufficient. The inner chaos demanded inner narration. Enter stream of consciousness, fractured chronology, and surreal juxtapositions. The literature of this period doesn’t report war — it mirrors its disorientation.

The press, the state, and even polite society struggled to maintain a façade of patriotic dignity. But the poets in uniform knew better. They saw not glory, but grotesque waste. As Robert Graves said, “The war was a mistake. And so was the literature that pretended it wasn’t.”

And still, they wrote.

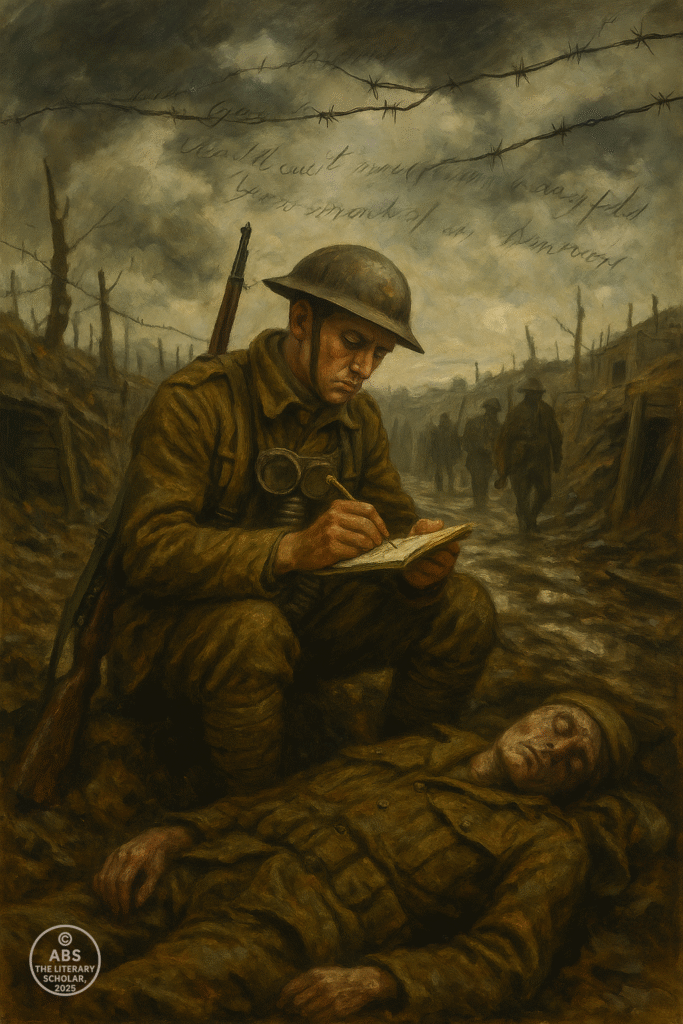

They wrote in dugouts by candlelight. They wrote on hospital beds. They wrote not to explain the war, but to survive it. Their words were bandages, protests, and tombstones.

This section — The Guns of August — is not a history lesson. It is an immersion. A walk through mud. A gasp for breath. A cry through the ruins of language. For when the world burns, the poet’s pen becomes both a weapon and a witness.

The Poets Who Bled on Paper: Brooke, Sassoon, Owen

They marched not only with rifles but with notebooks in their coat pockets. These were the men who carried the war into the realm of poetry — and poetry into the horror of war. Not generals, not kings, but young men with pens who became the truest chroniclers of the trenches. Their battlegrounds were not just Ypres or the Somme — they were metaphor, memory, and madness.

At first, there was Rupert Brooke. The golden boy of Edwardian verse. Handsome, lyrical, and infused with patriotic serenity, he embodied England’s last gasp of innocence. His sonnets, especially The Soldier, speak of noble sacrifice wrapped in pastoral softness:

“If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.”

Brooke never saw the worst of the war. He died in 1915 of blood poisoning en route to Gallipoli, still swaddled in the illusion of a meaningful death. His poetry reads like a eulogy for the England that believed in poetry as prayer and war as duty.

But then came Siegfried Sassoon — sarcastic, seething, and devastatingly lucid. A decorated soldier turned literary rebel, Sassoon didn’t just experience the war; he turned on it. His poetry is full of cold rage, targeting the hypocrisy of those who praised the war from parlors while boys died in mud.

“You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.”

Sassoon’s words were not designed to comfort. They were barbed wire dipped in ink. In 1917, he publicly refused to return to the front, publishing his Soldier’s Declaration, a bold act of protest against the continuation of the war. His punishment? Not court martial, but confinement in Craiglockhart War Hospital — a genteel euphemism for the shell-shocked and the seditious.

And there, at Craiglockhart, he met Wilfred Owen.

If Sassoon was the scalpel, Owen was the wound. Shy, gentle, and spiritually tormented, Owen’s poetry bleeds anguish. His verses are not shouts but tremors. He writes not to accuse others but to convey the incommunicable — the lived trauma of war, the drowning soldier, the taste of gas, the shattered faith of a Christian conscience.

“My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.”

That “old Lie” — sweet and fitting to die for one’s country — was Owen’s crucifixion. He dissects it line by line, word by word, turning Latin grandeur into mud-soaked irony. His use of half-rhymes — jarring, unsettled — reflects the broken rhythms of modern war and modern life.

Owen, like Brooke, died young — at just 25, one week before the Armistice. His mother received the telegram on Armistice Day, while church bells were ringing for peace. It is perhaps the most devastating irony in all of English letters.

Together, Owen and Sassoon redefined war poetry. They replaced the trumpet with the whimper, the drumbeat with the heart murmur. They taught literature to shudder, not march. Their legacy was not patriotism, but truth — uncomfortable, bloodied, necessary truth.

And they were not alone. Isaac Rosenberg, a Jewish working-class poet, and Ivor Gurney, a composer as much as a writer, both brought diversity and complexity to trench verse. Gurney’s mind was fractured by gas and grief; Rosenberg was killed on night patrol, but not before writing lines that cut through romantic nationalism:

“I am determined that this war, with all its powers for devastation, shall not master my poeting. That is my prayer and my aim.”

That sentence could be the anthem of this generation. They did not let the war master their poeting. They let their poeting master the war. It was not about survival, but about testimony. Not heroism, but honesty. Not memory, but scar.

These men, these poets — Brooke, Sassoon, Owen, Rosenberg, Gurney — became the conscience of their age. They turned the war from a geopolitical narrative into a human tragedy, one stanza at a time.

And when we read them now, over a century later, it is not to revisit a syllabus. It is to step into the boots of those who bled through lines, not just wounds. They are not just literary figures. They are oracles, warning us of what happens when empires dream and humanity sleeps.

“A Mind in Ruins”: Shell Shock and the Shattering of the Psyche

If war was a theatre, the most tragic drama played out not on the battlefield but in the minds of its survivors. By 1916, the war had invented a new kind of casualty — not of flesh, but of memory, language, and sanity. “Shell shock,” they called it — a term as vague as it was revolutionary. It marked the point when modernity first stared into the abyss of the human mind and found not courage or clarity, but collapse.

The old language of masculinity — stoicism, discipline, gallantry — cracked under the pressure of trench warfare. What words could capture the sound of endless bombardment, the sight of limbs flung into trees, the smell of blood thickened with mud? What metaphor could contain the reality of rats eating the dead, or the silence after a gas attack? The soldier’s psyche, once armored in duty, began to splinter — not out of weakness, but out of overload.

These were not cowards. They were men whose minds had simply run out of space.

Some trembled endlessly. Others lost the ability to speak. Still more became trapped in time loops, reliving the same horror as if the shell had never stopped falling. Military doctors were unprepared. Some blamed degeneration. Others accused the sufferers of malingering. But a few — like Dr. W.H.R. Rivers at Craiglockhart War Hospital — began to understand: the trauma was real, and it had no bullet wound to point to.

Literature, that old chronicler of kings and conquests, now turned inward — toward the battlefield of the self.

The war poets began capturing not just death but derangement. Owen’s poems don’t just depict external violence; they document the internal haemorrhage of a moral imagination. In “Mental Cases,” he writes:

“These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished.

Memory fingers in their hair of murders,

Multitudinous murders they once witnessed.”

The dead do not stay dead in Owen’s world. They claw their way into dreams, into waking moments, into poetry. Sassoon, too, offers us men who can no longer return to normality — who stare at the calm countryside with eyes that have seen too much. His short story “Counter-Attack” shows a protagonist torn between numbness and rage, unable to reconcile what he’s seen with the lies of a decorated narrative.

This psychic rupture also began to haunt the novel. The war fractured narrative as much as it did minds. No longer could stories proceed from A to B. Cause and effect — the bedrock of the 19th-century novel — were now unreliable, as was memory, as was language itself.

The early tremors of this shift are visible in writers like Ford Madox Ford, whose Parade’s End sequence tracks the disintegration of aristocratic certainty through a protagonist who feels time collapse, love falter, and war obliterate all fixed meaning.

Even more significantly, the war indirectly fertilized the literary ground for modernist interiority. James Joyce, though not a soldier, wrote Ulysses in a Europe deeply altered by war’s psychic debris. Virginia Woolf, too, heard the echoes. Though her Mrs. Dalloway appears to unfold in postwar peacetime, it is haunted by the figure of Septimus Warren Smith — a former soldier suffering from shell shock, hallucinating Evans, his dead friend, and eventually jumping from a window. His inner turmoil is described with a chilling tenderness:

“He had gone through the whole show — friendship, European war, death — had gone underground…”

Septimus is not a side character. He is the shadow-self of modern civilization. And through him, Woolf writes the war without showing the trenches — only the aftermath stitched into the brain.

The war also summoned new narrative devices — stream of consciousness, fragmented time, unreliable narrators — not for art’s sake, but for truth’s sake. The mind could no longer be a stable mirror. It had to be a cracked kaleidoscope, reflecting trauma in broken images.

Thus, literature became therapy, protest, and confession — all in one. It gave voice to the voiceless, not through slogans or manifestos, but through haunted whispers, half-finished sentences, and surreal visions. Art was no longer a mirror held up to nature. It became the bandage over the wound, or sometimes, the wound itself.

This was a pivotal moment in literary history: the collapse of external certainty led to the exploration of internal catastrophe. The novel became less about plot and more about perception. The poem became less about form and more about fracture. The protagonist was no longer the hero, but the haunted.

And that shift — from the battlefield to the broken mind — shaped everything that followed in literature. It is here, in the cracked shell of modern consciousness, that the modern novel and modern poetry were born.

“Fiction Goes to War: Novels in Uniform”

If poetry bled in the trenches, fiction marched alongside—stumbling through mud, buried under lies, resurrected by conscience. The First World War did not just claim bodies; it unmoored storytelling itself. In the mud-stained diaries and semi-fictional accounts of the time, the novel underwent an identity crisis: could it still tell stories when meaning itself had collapsed?

Gone were the polished plot arcs of the Victorian novel. War refused to behave like a narrative. It offered no clear villains, no satisfying resolutions. What fiction encountered in Flanders and Gallipoli was a chaos immune to moral framing. The very act of narrating war became a challenge — to ethics, to aesthetics, to sanity.

One of the earliest and most significant responses came from Henri Barbusse, a French novelist and former soldier, whose 1916 novel Le Feu (Under Fire) was both reportage and rejection. Its fragmented style and raw vignettes of trench life dismissed glory and heroism as bourgeois illusions. Barbusse gave the war a visceral honesty that made both governments and idealists uncomfortable.

In Britain, Frederic Manning‘s Her Privates We (published anonymously in 1929) told the tale of a thoughtful private named Bourne. The language is restrained, the style modernist in understatement. Bourne is not a hero. He is an observer — weary, intelligent, and numb. Through his eyes, the absurdity of war is not screamed but murmured with quiet dignity. The title itself is a Shakespearean euphemism, mocking the very idea of decorum in the face of mud, lice, and death.

Meanwhile, Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End series (1924–28) stands as one of the most ambitious war-centered works of the period. It chronicles the disintegration of aristocratic values and the rise of the mechanized state through Christopher Tietjens, a stoic man crumbling under the weight of modernity. Ford’s prose mirrors the psychological fragmentation of war. Time jumps, perspectives shift, memories collapse — the war does not progress; it seeps.

And while much of this fiction came from men in uniform, women were also shaping the wartime narrative. Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (1918) is a searing novella that confronts war-induced amnesia with gendered insight. The soldier returns home but not to his wife — to a simpler past, a former lover. His memory has retreated from modern pain to romantic nostalgia. Here, war erases not just chronology but emotional reality. West writes with a clinical compassion that reveals how women, too, bore the war — through caregiving, silence, and unresolved grief.

Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth (1933), though technically a memoir, reads like a novel. Brittain, a nurse who lost her fiancé, brother, and closest friends, delivers a devastating chronicle of innocence annihilated. Her prose is elegant, never indulgent. She is not merely a victim; she is a chronicler of cultural disillusionment. Through her eyes, we see the war not only as masculine loss but as the betrayal of an entire generation’s promise.

The war novel thus became a hybrid form — part documentary, part lamentation, part rebellion. It blurred genres because the war itself defied categorization. This was not a tale of gallant battles and noble speeches. This was the age of machine guns, mustard gas, and bodies never found. Fiction had to adapt.

Indeed, this period saw the emergence of the anti-narrative: stories that questioned not only war, but storytelling itself. What is the point of plot when the world has no arc? What is character when identity itself dissolves under trauma?

Even the enemy, once cartoonish in patriotic pulp, began to appear as human. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928), though German, struck chords worldwide. It depicted young Paul Bäumer and his comrades not as fanatics, but as frightened boys caught in a machinery that chewed up dreams. The novel’s cold precision, its utter rejection of rhetoric, made it perhaps the most honest war novel of all — and also one of the most censored.

What united these works was not style or nationality but the tone of despair. Modern war demanded modern fiction — elliptical, disillusioned, bloodied with truth. There were no victors on these pages. Only survivors who learned that silence sometimes speaks louder than slogans, and that the most heroic act was to endure without madness.

Fiction in the Great War did not simply tell the story — it redefined how stories could be told. It rejected the pageantry of patriotism and embraced the fragile, fractured self. The battlefield had entered the sentence.

And literature would never be the same.

“Letters from the Edge: War Diaries, Memoirs, and Trench Testimonies”

When truth became too raw for fiction, men reached for paper not to publish — but to survive. The trench diary and the soldier’s letter became the most intimate literary forms of the Great War. These were not performances. They were confessions scratched between bombardments, love letters stained with mud, jokes whispered in ink before death could interrupt the punchline.

Unlike state propaganda, unlike polished poetry, these fragments were immediate, unfinished, often unfiltered. They reveal war not from the eagle-eyed strategist’s perch, but from the worm’s view — where lice, rats, rain, and silence gnawed more cruelly than enemy fire.

In one letter home, a British private wrote:

“We sleep in holes, we eat out of cans, we speak in monosyllables. We are not men, not anymore — we are reactions to noise.”

These writings resist aesthetic beauty. Their power lies in the nakedness of voice. Soldiers described trench foot and frozen tea, the stench of corpses mingled with wet socks, and the dull wait for death that came not with drama, but with routine. These were not stories of battle, but stories of boredom, endurance, and the tiny rituals that kept madness at bay.

“The front is not heroic,” wrote an Australian corporal, “It is a farmyard made hell.”

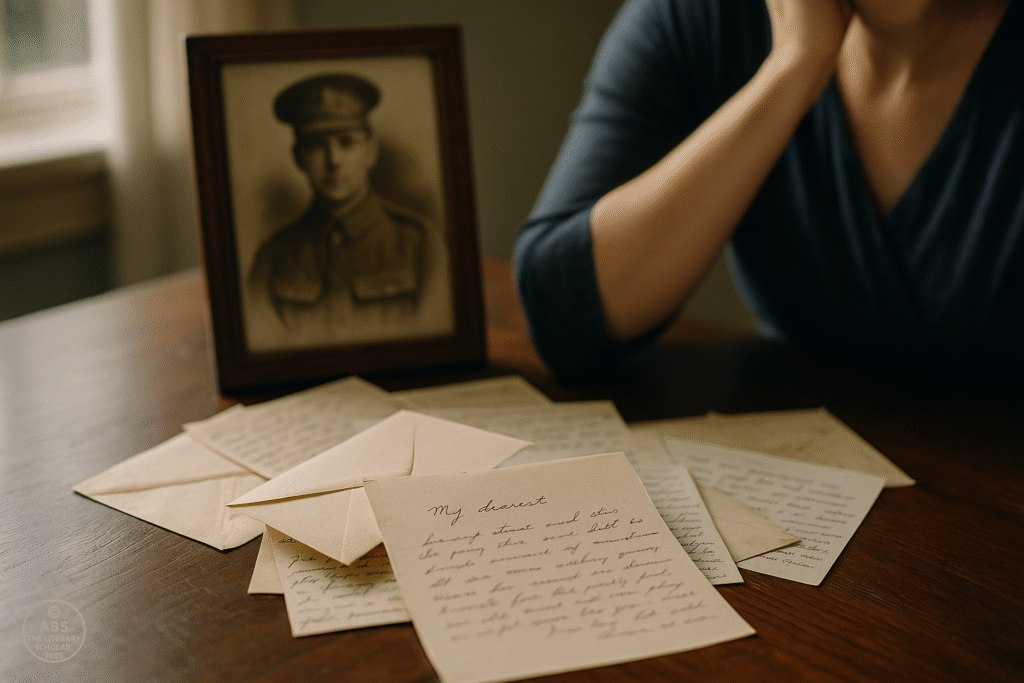

Perhaps the most heartbreaking are the letters written just before death — a goodbye penned in shaking hand. Wilfred Owen’s final letter to his mother, dated just a week before he was killed, reads with a tragic foresight. He tells her not to worry, that spirits are high, that he will be home soon — and yet the subtext trembles with the unspoken.

“I came out in order to help these boys — directly by leading them as well as an officer can, indirectly by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them.”

(Wilfred Owen, October 31, 1918)

He never did speak of them again. He was killed on November 4 — one week before the Armistice.

Some soldiers carried notebooks in their pockets, scrawling what they could not say aloud. The trench diary of Lieutenant J.R. Ackerley, for instance, is both mundane and metaphysical:

“Sent for rations. The ham was mostly string. Thought about death. Wrote a haiku. Survived the shelling.”

Others, like Siegfried Sassoon, initially poured anger into diary entries before publishing censored versions. Sassoon’s real-time journals are more volatile than his crafted poetry — filled with guilt, sarcasm, and disillusionment.

He writes of officers more concerned with tea than tactics, of suicidal boredom, and of the surreal absurdity of war bureaucracy.

These documents have become more than historical artifacts — they are the emotional fossils of a generation. They carry the fingerprints of boys who never became men, who died with sentences unfinished, metaphors half-formed, letters unsent.

Even the short memoirs, such as Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War, are saturated with quiet horror. Blunden’s voice is gentle, yet the images he records — a comrade’s boot with a foot still inside, the quiet moan from a shattered dugout — pierce more sharply than any shouted slogan.

The war memoir emerged as a kind of literary purgatory — a space between testimony and therapy. It was never objective. It could not be. These were not stories of national glory, but autopsies of the soul.

And here is the cruel paradox: those who returned and wrote often felt more guilt than pride. They had survived — but who had they become? Their pens scratched not for praise, but for penance.

These wartime writings remind us that the Great War was not fought only with guns and gas — it was also fought with fountain pens, stubby pencils, and words pressed into envelopes. They are the ghost-scribbled margins of history, the breath that lingers after the bugle falls silent.

In reading them, we do not just remember the war — we feel it breathing behind the ink.

“Women at War: Nurses, Writers, and the Home Front Voices”

The trenches may have been filled with men, but the echoes of war reverberated through parlors, hospitals, and quiet bedsides where women waged battles of their own — against silence, grief, and prescribed invisibility. World War I was not only fought with bullets and bombs, but with ink and gauze, with whispered prayers and unwritten dreams.

While male soldiers were being shattered at the front, women were redefining their roles in society and in literature. They were not passive observers. They were healers, chroniclers, and revolutionaries in waiting.

In field hospitals stained with mud and morphine, women like Vera Brittain and Mary Borden tended to the broken bodies of youth — sometimes strangers, sometimes lovers. They stitched together limbs, but could not stitch together the crumbling idea of a stable world. Their memoirs are not simply records of service; they are acts of resistance — against erasure, against numbness.

“I shall go on alone, and I shall not live in vain.”

— Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth

Brittain’s voice — raw, clear, and defiant — became one of the most powerful chronicles of a generation that lost more than it understood. Her fiancé, her brother, her friends — all gone. Yet her writing remained. Her grief became a mirror in which a grieving nation saw itself.

Mary Borden, an American nurse working with British troops, gave us The Forbidden Zone, a haunting, lyrical record of wartime horror written not with patriotic rhetoric, but with poetic intensity. Borden defied expectations — not merely by writing about war, but by refusing to prettify it.

“This is not a story. It has no beginning and no end. It is a cry of pain.”

Meanwhile, on the home front, women filled the gaps left by absent men. They worked in factories, drove ambulances, joined the Land Army, taught in classrooms — and wrote. Their pens challenged the myth that courage wore only trousers.

Rebecca West, with biting intelligence, condemned the war’s absurdity and exposed the gendered hypocrisies that underpinned nationalistic fervor. Her journalism and fiction — especially her novel The Return of the Soldier (1918) — questioned the morality of a society that demanded men die like heroes and women wait like saints.

In The Return of the Soldier, West explores not only the trauma of war but also the suppressed emotional cost paid by women — wives, cousins, caretakers — whose roles were written not by choice, but by social script.

“Love has no sense of time. It can wait forever.”

— Rebecca West

Women poets, too, began to appear — often marginalized but undeniably powerful. May Wedderburn Cannan, Charlotte Mew, and Margaret Postgate Cole wrote of grief, of patience turned into despair, of feminine strength that needed no uniform.

And yet, even as women claimed space in literature, they were often omitted from the post-war literary canon. Their sorrow was considered domestic, their voices too quiet for the grand narrative of heroism. But it is these voices that capture the quieter devastations — the slow deaths that came not from shrapnel, but from waiting.

The war brought a tectonic shift in the gender dynamic of literature. It became harder to write about womanhood in pastel. The war had darkened the palette. Women had seen blood. They had heard the screams. And they had chosen to write — not about lace and longing, but about loss, rage, and resilience.

Modernism would eventually celebrate male fragmentation and masculine despair. But in the shadows, women were writing their own modernism — one not always experimental in form, but revolutionary in content. They questioned roles, redefined purpose, and demanded to be remembered not as muses or mourners, but as witnesses.

Their war was not in the trench. It was in the silence after the telegram arrived.

It was in the hospital tent that smelled of gangrene and lavender.

It was in the decision to write when the world wanted them quiet.

They did not fire rifles. They fired truths.

And in the brittle pages of their memoirs and novels and poems, we hear not only what the war did to women — but what women did to the war.

Artillery and Avant-Garde – The Rise of Modernist Experimentation

War may devastate bodies and borders, but it also detonates forms of thought. As the guns thundered across Europe, the rules of literature — structure, style, subject — collapsed under the same weight that broke empires. If the old world had died, how could its narratives survive? From the shrapnel of tradition, writers began reconstructing meaning with fragments, silence, and startling innovation.

This was not merely aesthetic rebellion. It was literature attempting to speak the unspeakable — to give form to the formless trauma of mechanized slaughter, senseless death, and moral disorientation. Modernism did not “begin” in 1914. But it bled its fiercest colors during the war.

In London and Paris, the war catalyzed a movement already simmering with dissatisfaction. In the cafés and journals of Bloomsbury and Montparnasse, artists and authors began crafting not escape, but interrogation. The novel could no longer be a tidy arc; the poem could no longer be a predictable rhyme.

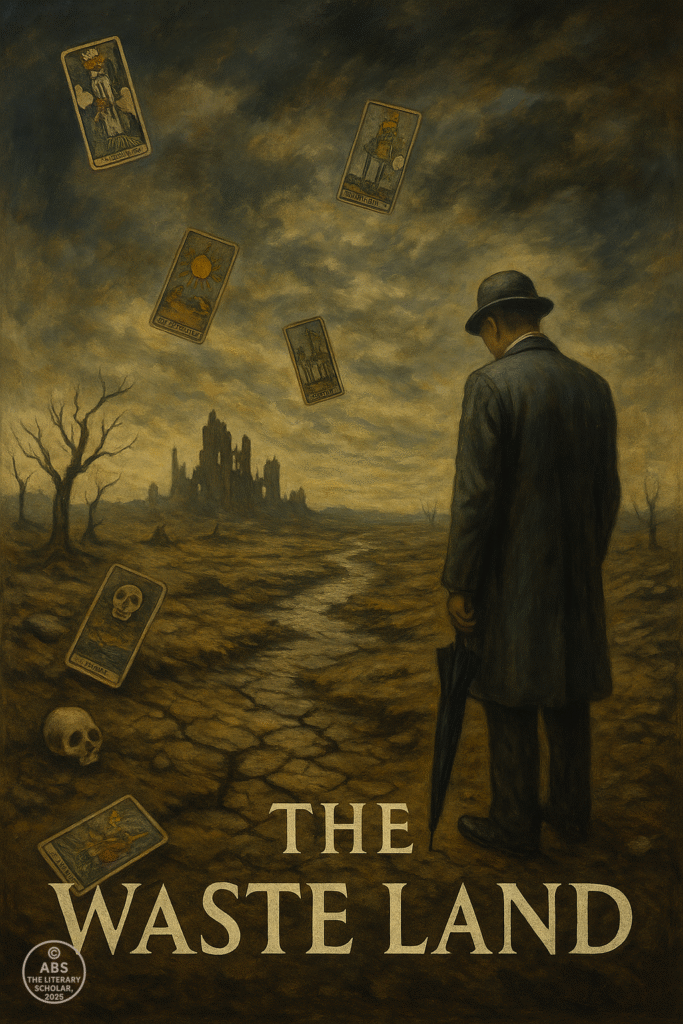

“These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

— T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

Though The Waste Land was published post-war, its psychological terrain is pure war-scarred ground. Eliot offered a world of voices, ruins, echoes — a modern Jerusalem built from broken glass. The war made faith obsolete, coherence a myth, and language a battlefield.

Meanwhile, Virginia Woolf was busy redefining the interior life. In Jacob’s Room (1922), she writes a fragmented, impressionistic elegy for a young man lost to war. The novel is not about war scenes — it is about absence, the space where a life once was. She understood that war hollowed not only homes but consciousness itself.

“Let us record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall…”

— Woolf’s manifesto for modern fiction

Modernism became, above all, a response to dislocation. Stream of consciousness, disrupted chronology, interior monologue, mythic method, elliptical syntax — these were not stylistic fads but literary survival strategies.

James Joyce, already pioneering new forms, now plunged deeper. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) reflected the rebellion of the self in a society paralyzed by paralysis. The war is distant in setting, but omnipresent in emotional mood — a generation unsure of its future, riddled with contradiction.

And in the visual arts, Cubism, Futurism, and Dada exploded like grenades at a gallery opening. The human form was distorted, language mocked, and order scorned. The Dadaists, born in Zurich’s cafés while Europe bled, rejected all rationality — because reason had led to war.

“DADA means nothing. If you find it absurd and meaningless — we agree.”

In this environment, literary manifestos were hurled like grenades. Pound’s cry to “Make it new!” became a battle standard. Poetry trimmed its fat. Language became surgical. Meaning had to be carved from chaos.

The Avant-Garde was not a sidebar to war literature — it was war literature in another uniform. It bared the raw nerves of a civilization undergoing nervous breakdown. The battlefield had moved from Flanders to the page — but the screams were real.

Even plays responded to this fracturing. Though the full flowering of absurdist drama would come later, the seeds of disjointed dialogue, anti-heroic structure, and existential inquiry were sown in this period.

Literature could no longer lie politely.

Art had to bleed. Syntax had to stutter. Coherence had to crack.

And the result? A modernism that did not mourn the past — it autopsied it.

The Empire Writes Back – Colonial Echoes and Dissent

While European cannons thundered across Belgium and France, another war was quietly erupting — a war of voices long silenced by empire. Beneath the polished veneer of British propaganda, cracks were widening across the colonial world. If the Great War promised to “make the world safe for democracy,” it also forced the Empire to confront the lies it had written into its own story.

From India to Africa, from the Caribbean to Egypt, colonial subjects were dragged into a European conflict they had no hand in starting. Over one million Indian soldiers served in the British Army, many fighting in bitter European winters and Mesopotamian deserts for a king they had never seen. African conscripts died in campaigns far from home, their names unmarked in Western war memorials. Their blood soaked foreign soil, but their stories were rarely allowed to bloom.

“We are no more the subjects of a distant monarch than the conscripts of a foreign ambition.”

— From a speech by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (paraphrased)

But while the battlefield silenced many, colonial pens began to stir. In drawing rooms and local presses, in poems and protest pamphlets, the war years ignited literary dissent. It wasn’t always overtly revolutionary — sometimes it was subtle, symbolic, simmering.

Rabindranath Tagore, already a Nobel laureate by 1913, shocked the British establishment by renouncing his knighthood in 1919 after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. He wrote not with anger but with dignified disillusionment, turning his poetry into quiet rebellion. “Where the mind is without fear…” took on a sharper resonance in a world soaked with imperial blood.

Meanwhile, African voices began emerging in mission schools, in oral traditions transcribed under colonial oversight, and in English-language journals. These early fragments — letters, prayers, autobiographies — were seeds of literary defiance, echoing the contradictions of loyalty and loss. The native soldier’s gun may have pointed outward, but his heart was often turned inward — questioning, aching, evolving.

“Why fight for the flag that flogs me?”

— Anonymous Indian soldier’s lament (oral record)

Back in England, the very notion of the British Empire as a civilizing force was losing its shine. Writers like E.M. Forster explored the cultural chasms in novels like A Passage to India (1924), gestating during the war years. The Marabar Caves echoed the silence of misunderstanding, colonial guilt, and a friendship impossible under imperial strain.

The myth of white superiority, already fraying at the edges, began unraveling. The trenches had made it clear: death made no distinctions. The Indian sepoy and the British lieutenant fell side by side. Only their memorials differed.

This dawning awareness fed into a post-war literary consciousness that could no longer ignore the suppressed. The modernist fragmentation of the West had a parallel in the fractured loyalties of colonized minds — loyal to the English language, yet subversive in spirit.

Even within Europe, the Celtic fringe — Ireland, Scotland, and Wales — raised its voice. The Easter Rising of 1916 wasn’t just a political event — it was a literary rupture. W.B. Yeats’s “Easter, 1916” mourned the dead with the ambivalence of a poet caught between admiration and anxiety. “A terrible beauty is born.”

Modernism may have been born in London, Paris, and Vienna — but its echo chambers resounded in Calcutta, Cairo, Lagos, and Dublin. The war unshackled a multilingual modernism, one that would later become a deluge in postcolonial literature.

And while the British canon was still reluctant to admit these voices, they were writing anyway — writing in margins, in exile, in translation, in fire. Part 2 closes with the quiet hum of that awakening — for though the guns fell silent in 1918, the pens in the colonies had just begun to sharpen.

Aftermath and Amnesia — The Lost Generation and Literary Memory

When the last rifle fell silent and the armistice was signed in a secluded railway carriage in Compiègne, the world did not erupt in triumph. It exhaled — raggedly, bitterly — as if unsure whether to mourn or to forget. The “War to End All Wars” had instead ended the illusion of permanence, honour, and heroic sacrifice.

Europe, once the cradle of Enlightenment and Empire, now looked like the ward of a sanatorium. Cities had crumbled. Faith had fractured. And literature, that old guardian of civilization, stood stunned and disoriented amidst the ruins.

A new phrase emerged from the literary salons of Paris and New York — “The Lost Generation.” Coined by Gertrude Stein and immortalized by Hemingway, it described not merely those who had fought and died, but those who had lived on with nothing left to believe in. They were not just lost to war. They were lost to meaning.

“You are all a lost generation.”

— Gertrude Stein to Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway’s prose in The Sun Also Rises (1926) sliced like shrapnel — blunt, sparse, emotionally scorched. His characters wandered through cafes and bullfights, looking for thrill, sex, drink — anything to silence the echo of what had been shattered.

“Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

— Jake Barnes, quietly dismantling the last illusion of romantic hope

F. Scott Fitzgerald, in Tender Is the Night and later The Great Gatsby, chronicled the glittering decay of post-war idealism. Jay Gatsby’s dream died not in the trenches but in the jazz-soaked, hollowed-out extravagance of the 1920s. The green light blinked — not with promise, but with irony.

Virginia Woolf, walking the Thames with pebbles in her pocket and genius in her prose, turned inward. Her Mrs Dalloway (1925) wasn’t just about Clarissa’s party — it was also about Septimus Smith, a war veteran who heard birds speaking Greek and couldn’t re-enter the world he had supposedly fought to save.

“The war was over, except for someone like Septimus, who continued to fight it in his head.”

— Paraphrased from Mrs Dalloway

T.S. Eliot gave the most enduring elegy of all. The Waste Land (1922) wasn’t a poem. It was a cultural autopsy. The corpse of civilization was dissected in five jagged movements, stitched together with Sanskrit, Dante, nursery rhymes, and regret. Water, once a symbol of renewal, became a symbol of absence. There was no redemption in the rain — only fragments shored against ruin.

“These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

— The Waste Land

The post-war psyche was haunted by memory and forgetting. Nations wanted to remember their victories, but not their mistakes. War memorials rose like altars — but the poets who had exposed the folly of generals and the agony of privates were often left out of schoolbooks.

What was remembered was sanitized — what was felt was buried. In England, Siegfried Sassoon was institutionalized. In Germany, Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front was later banned. History preferred heroes. Literature offered ghosts.

And yet, the literary memory would not fade. It bled through novels, letters, memoirs. It questioned glory. It mocked nationalism. It humanized the enemy. Above all, it mourned not just the dead, but the loss of belief — in progress, in certainty, in narrative itself.

This is why the modernist style — fragmented, ironic, nonlinear — was not just a stylistic rebellion. It was a psychological necessity. How could one write straight when the world had bent and broken?

The post-war literary field became a terrain of wreckage — and reinvention. Novelists, poets, and playwrights were no longer custodians of tradition. They were witnesses. Survivors. Skeptics. Builders of new forms for a new, fractured age.

Part 2 ends where the war ended — in uneasy silence. Not with triumph, but with a question mark, blinking in the ashes. The cannon had stopped. But in literature, the sound would never cease.

But not all modern voices were fragmented. Some rose with prophetic defiance and cold clarity — W.B. Yeats and W.H. Auden among them.

Yeats, who had once conjured Celtic twilight and mystical roses, stood tall in this twilight of empires. His tone was neither naïve nor broken — it was oracular. As the war ended and the Irish struggle intensified, Yeats turned his gaze on the chaos of the century and dared to speak its terrifying rhythms.

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.”

— The Second Coming, 1919

His post-war poems — from The Second Coming to Sailing to Byzantium — were not merely reactions; they were warnings wrapped in symbols. Byzantium, gyres, rough beasts, and golden birds replaced the pastoral and the romantic. Yeats didn’t describe the broken age — he mythologized it. And in doing so, he offered what no trench report could: the spiritual dread of modernity.

In contrast, W.H. Auden arrived slightly later but bore the same gravitas — the calm voice in a storm of collapse. In his early poetry, Auden mapped the psychological wasteland of post-war Europe: disillusioned cities, crippled faiths, political anxiety. His pen was scalpel and compass — cutting, but also orienting.

“We must love one another or die.”

— September 1, 1939

This was not romantic pleading. It was a moral imperative carved into the conscience of a century on the brink again. Auden didn’t scream. He whispered — and in that whisper, one heard the death of innocence and the burden of responsibility.

So, between Eliot’s ruin, Yeats’s revelation, and Auden’s reflection, modern poetry became a triptych of existential inquiry. Each poet carried a different wound. Each warned in a different tongue.

The Century Bleeds: Voices from the Front and the Fringe

This second scroll did not speak—it howled. From Brooke’s patriotic hope to Owen’s bitter pity, from trenches soaked in death to drawing rooms echoing with doubt, literature here became the battlefield. Every metaphor became a mourning. Every stanza, a grave.

The war did not end with the armistice.

Its tremors travelled in blank verse, surreal paragraphs, and the fractured self.

Yeats turned and turned in widening gyres. Eliot buried the dead in April.

And Auden charted Spain while time disintegrated.

This was not merely literature reacting to history—it was language remade by trauma.

And it taught us: when the world breaks, writers do not mend it.

They illuminate the cracks.

Signed,

The Professor’s Desk

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance