Victorian Poetry between the Pull of the Past and the Pressure of Progress (1832–1860s)

From The Professor's Desk

PRELUDE: From Romantic Rhapsody to Victorian Realism

Literary history never begins or ends cleanly at a monarch’s coronation, or with the signing of a single Act. Yet in the England of the 1830s, a series of tremors was shaking the foundations of both society and art — tremors that would give birth to the vast edifice we now call the Victorian Age.

The high music of Romanticism, once echoing across the hills and valleys of poetry, was already fading. The great voices — Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats — had sung of individual emotion, nature’s grandeur, and the sublime spirit of the universe. But the England they had once wandered so freely was changing beneath their feet.

By 1832, the first wave of political and social reform broke upon the British Parliament. The First Reform Act — a landmark moment — extended voting rights to the middle classes, dismantling some of the archaic privileges of the landed gentry. It was an act born of necessity: industrial cities had swelled, their laborers crowded in grim tenements, while chimney sweepers — mere children — blackened by soot, climbed perilous flues for pennies. Child labor, urban poverty, and working-class exploitation stood in stark contrast to the wealth of empire.

The Reform Act, though limited, marked the first formal acknowledgment that Britain must change—and with it, so too would its literature. No longer could poets and novelists afford to stand aloof, praising nature or dwelling solely in personal reverie. The steam engine, the factory, the railroad, the widening web of empire—all demanded new ways of seeing, new voices to speak.

Meanwhile, across the Channel, scientific discoveries and industrial marvels challenged the old certainties of Christian faith. The Victorian mind would live in a state of uneasy negotiation—caught between the comforts of belief and the relentless questioning spirit of science.

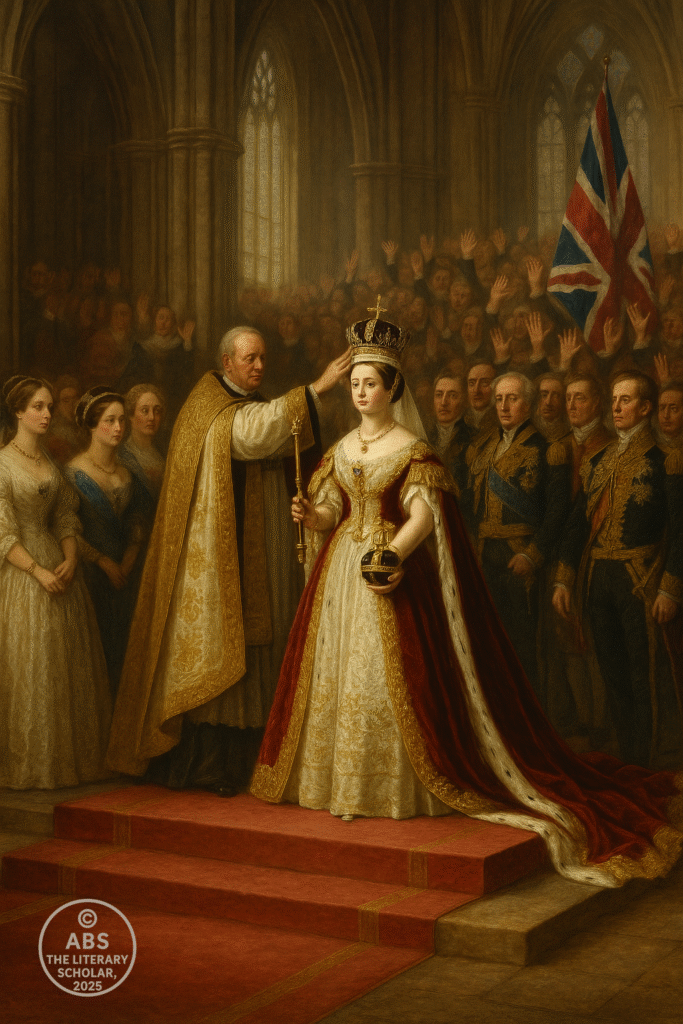

And then came 1837. Queen Victoria, at just eighteen, ascended a throne that commanded a global empire. Over the next sixty-four years, she would preside over Britain’s most expansive century—an era of imperial confidence, technological innovation, and profound social anxiety. “The sun never sets on the British Empire,” Victorians would proudly declare—but beneath that sun lay shadows they could neither ignore nor fully illuminate.

It is here—at this fragile, fertile moment—that we begin the long scroll of Victorian literature. A literature that would echo with the grand cadences of Tennyson, the penetrating psyche of Browning, the melancholy wisdom of Arnold; a literature that would unfurl through the sprawling fictions of Dickens, Eliot, and the Brontës; a literature that would end, at last, at the trembling brink of modernity.

The age of innocence had passed. The age of complexity had begun.

Let us turn the scroll.

Shadows of Change, Voices of Faith and Doubt

Victorian Poetry between the Pull of the Past and the Pressure of Progress (1832–1860s)

The Spirit of an Age Awakened

The Aftermath of the 1832 Reform Act and the Victorian Crisis of Faith

Literature is the mirror of an age, but not all ages enjoy their reflection.

By the dawn of the Victorian period, Britain was both proud and haunted—a nation that had built an empire yet was unsure of its soul. The poets who inherited this world would not sing of daffodils and solitary walks, as their Romantic forebears had done. They would be called upon to speak to a society caught in the hard gears of industrial modernity, caught between the dream of progress and the growing terror of moral and spiritual decay.

The First Reform Act of 1832 cracked open the door to change. For centuries, the British electoral system had been a corrupt relic; entire cities of the new industrial heartlands had no parliamentary representation, while empty fields sent members to Westminster. The Act gave voice—albeit limited—to the burgeoning middle class, leaving the working poor still disenfranchised, but it was a signal: the old order would no longer suffice. Alongside this political shift came growing outrage over child labor, including the gruesome lives of chimney sweepers, forced into narrow flues where they suffocated in soot or perished unseen. Public conscience stirred, and legislation against such abuses began to emerge.

Yet while Parliament debated policy, Britain’s streets told another story. The rise of the industrial city brought new forms of misery: smoke-choked skies, overcrowded slums, diseases bred in stagnant air. The pastoral ideal of the Romantics seemed hopelessly naive in Manchester or Birmingham. The Victorian poet was born into a world of steam engines and skepticism, not rustic bliss.

Science advanced relentlessly. The publication of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830–33) shook belief in a world created in six days. The mechanical precision of the universe, revealed by new discoveries, left little room for divine mystery. When Charles Darwin would publish On the Origin of Species in 1859, the crisis would deepen, but already the Victorian mind was wrestling with a profound split between faith and reason.

Religious doubt, once whispered, now began to speak in the language of poetry. The great Victorian crisis of faith had begun—not a wholesale abandonment of belief, but an anguished struggle to reconcile it with the facts of an altered world. Matthew Arnold would later give this struggle a haunting voice, but even in the 1830s and 1840s, poets felt the tremors beneath the polished façade of progress.

The role of the poet itself had changed. In the Romantic age, the poet was a seer, a lone visionary communing with nature. Now, the Victorian poet stood before a fractured audience: the educated middle class demanded moral guidance, the working poor sought truth in their struggles, and the aristocracy wished to see its values affirmed. To speak to such a divided nation, poetry had to evolve. It could no longer be a private reverie; it must become a public utterance, a form of social conscience.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, who would become the century’s most celebrated poet, recognized this need. His verse, though steeped in the lyric beauty of the Romantics, bore the weight of a new moral seriousness. Robert Browning, more intellectually daring, crafted dramatic monologues that exposed the dark intricacies of human nature—a mirror too candid for Victorian comfort. And in Matthew Arnold, the poet turned critic, the age found its truest voice of cultural self-examination.

Even as the empire expanded—“on which the sun never sets”, Victorians boasted—the shadow of spiritual uncertainty lengthened. In this paradox lay the heart of Victorian literature: an age of immense achievement and inward doubt. The poets of the early Victorian decades stood at the threshold of this contradiction, tasked with giving it voice.

As we turn now to their individual journeys—Tennyson’s elegies and grandeur, Browning’s psychological brilliance, Arnold’s melancholy wisdom—we must remember: they did not merely inherit a literary tradition. They were called to define an age that questioned the very meaning of progress, faith, and art itself.

Thus begins the first movement of Victorian poetry: shadows of change, voices of faith and doubt.

Alfred Lord Tennyson — The Laureate of Empire and Doubt

No Victorian poet wore the crown of public voice as fully as Alfred Lord Tennyson.

He was not merely a poet; he became, through the force of genius and circumstance, the Laureate of the British Empire itself—the one whose verse would accompany the Empire’s triumphs and mourn its tragedies. Yet beneath the measured cadence of his lines, one hears always a deeper tension: the mind of a man who believed in progress, but who also knew too well that progress demanded losses the heart could scarcely bear.

Tennyson’s ascent to national prominence was slow and not without struggle. Born in 1809, at the dawn of the nineteenth century, he belonged technically to the post-Romantic generation, yet his early verse owed much to Wordsworthian nature and the rich Gothic imagination of Keats. He read Homer and Virgil with reverence, but also absorbed the modern anxieties that were reshaping the England of his youth.

When Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, Tennyson was still finding his voice. His early collections, particularly Poems (1832 and 1842), revealed a young poet captivated by the beauty of sound and image. Yet England itself had changed. Steamships, railways, and factory chimneys had transformed the landscape once idealized by the Romantics. Tennyson could not retreat entirely into pastoral dream; his poetry would have to face the present.

Art vs. Life — The Lady of Shalott

Nowhere is this early tension more vividly dramatized than in “The Lady of Shalott.” The Lady, confined to her tower, weaves a magic web, seeing the world only through reflections. “I am half sick of shadows,” she laments—a cry that resonates with an entire generation of artists confronting the relentless energy of an industrial age.

The poem poses a haunting question: Can art remain untouched by life? The Lady’s tragic fate suggests not. The Victorian artist could no longer dwell in ivory towers; the modern world, with all its brutal reality, would demand engagement.

Ulysses— Victorian Heroism and Stoicism

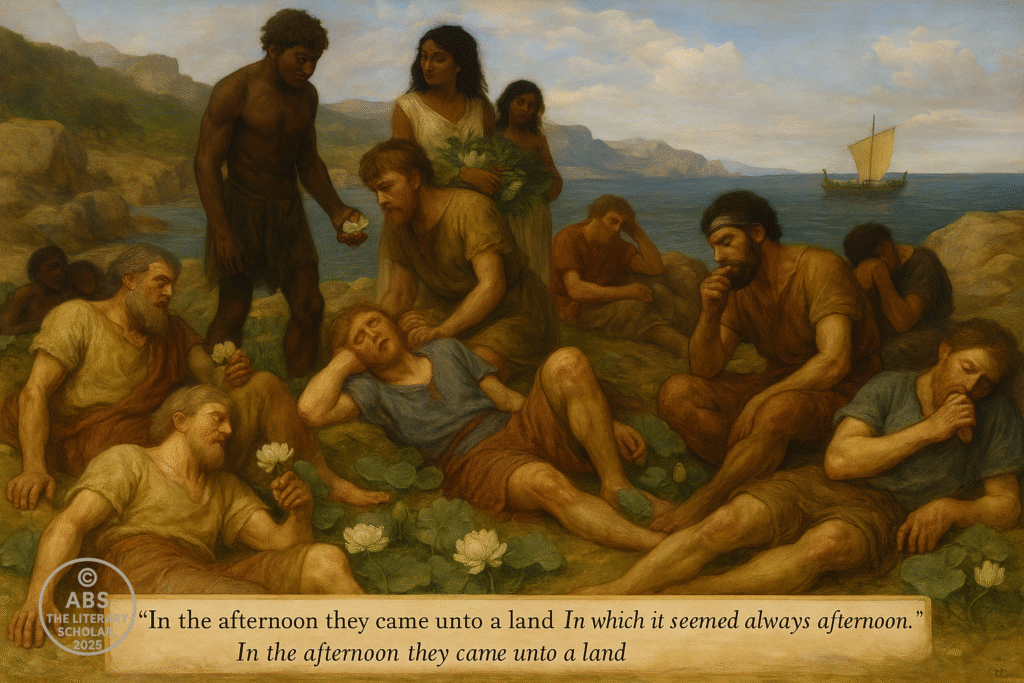

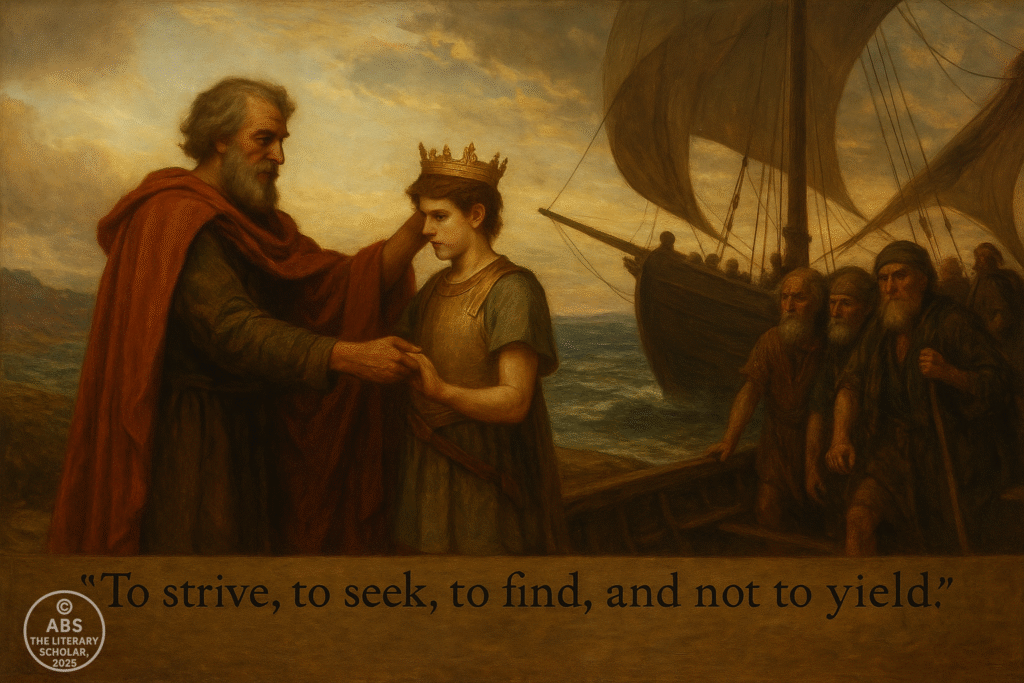

As Tennyson matured, his voice grew deeper, more resonant with the spirit of his age. In “Ulysses,” written after the death of his close friend Arthur Hallam, Tennyson gave Victorian readers one of their defining portraits of the modern self: weary, questioning, but unbowed.

“To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield” became a kind of unofficial motto for an empire that saw itself as both civilizer and conqueror. Yet the poem is more than imperial bravado; it is the soliloquy of a man who knows that great deeds cannot restore lost youth or lost faith. Beneath the outward stoicism lies a profound melancholy.

Victorian England, forging new empires and industries, shared this paradoxical mood: outward triumph, inward unease.

In Memoriam A.H.H. — Grief, Science, and Faith in Retreat

Tennyson’s most sustained meditation on grief and faith, however, came with “In Memoriam A.H.H.”—a monumental elegy written over seventeen years. Ostensibly a tribute to Hallam, the poem became for many Victorians a collective mourning song for an age of faith lost to scientific doubt.

The speaker of In Memoriam oscillates between yearning belief and tormented skepticism. In one of its most famous moments, he asks:

“Are God and Nature then at strife,

That Nature lends such evil dreams?”

Here is the Victorian crisis in its purest form: a universe governed by natural law that seems indifferent to human suffering. Tennyson’s struggle is not simply personal; it echoes the cultural anxiety of an England where Darwinian ideas were beginning to erode the old theological certainties.

Yet Tennyson, ever the Laureate, does not end in despair. The closing lines of In Memoriam seek a fragile reconciliation:

“One God, one law, one element,

And one far-off divine event,

To which the whole creation moves.”

It is not dogmatic faith, but a hopeful agnosticism—the best that many Victorians, caught between tradition and modernity, could manage.

The Laureate’s Burden

Appointed Poet Laureate in 1850, following the death of Wordsworth, Tennyson bore an immense public responsibility. His poems accompanied national ceremonies, royal marriages, and military campaigns. “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” written in response to the disastrous Crimean War charge, exemplifies the tension between heroic idealism and grim reality:

“Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die.”

These lines, both celebrated and critiqued, captured the martial spirit that would sustain Britain’s imperial ambitions—but also its moral blindness.

An Embattled Faith

By the later decades of his life, Tennyson remained a revered public figure, but also a poet increasingly aware that the Victorian synthesis of faith, science, and empire was unraveling. His late poem “Crossing the Bar” reads like a final benediction:

“I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.”

The hope is there—but the certainty is gone. This is the quiet wisdom of an age that had learned too much to believe too easily.

Tennyson’s genius lay in giving beautiful voice to the inner conflicts of his time. He was no radical; he stood with the establishment, yet his poetry shimmered with the anxieties that establishment could not silence. Victorian England heard its own doubts and dreams in his cadences. In him, the age found not a prophet of certainty, but a fellow traveler on the darkening road of progress.

As we turn next to Robert Browning, we shall encounter a voice more daring, more ironic—one less inclined to mourn the past, and more eager to dissect the present. The Victorian mind is many-minded indeed.

Robert Browning — The Voice of the Individual and the Dramatic Monologue

If Tennyson was the public conscience of Victorian England, Robert Browning was its unquiet soul.

Where the Laureate mourned the slow erosion of certainty, Browning plunged joyfully into the chaotic energies of human thought and feeling. His poems do not offer comfort; they pose riddles. His characters do not seek virtue; they reveal ambition, obsession, frailty, and raw desire. In an age desperate for moral anchors, Browning dragged the reader into the murky depths of the individual psyche.

Born in 1812, Browning grew up in an intellectually rich household. His father’s vast library and his mother’s devout nonconformist faith gave him both wide knowledge and sharp independence. From an early age, Browning was fascinated not with the heroic figures of myth or the grand abstractions of philosophy, but with the motives that drive men and women to speak and act—especially when those motives were morally ambiguous.

The dramatic monologue—his greatest formal invention—became the perfect vehicle for this exploration. In the monologue, a speaker addresses an unseen audience, and through their words, unintentionally reveals more than they intend. The form allows Browning to blur the line between speaker and poet, between confession and performance.

Victorian readers were both fascinated and unsettled. They expected poetry to uplift, to teach virtue. Browning’s verse instead exposed the shadows within respectable minds—an uncomfortable mirror for a society obsessed with appearances.

My Last Duchess — Power, Possession, and the Mask of Civility

Perhaps the quintessential Browning poem is “My Last Duchess.” A Renaissance duke casually displays a portrait of his late wife, offering a chilling glimpse of aristocratic control:

“I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together.”

In these curt lines lies a world of unspoken violence. The Duke’s polished speech, full of aesthetic appreciation, cannot conceal his jealousy and authoritarian impulse. Victorian readers, priding themselves on moral progress, saw here an unsettling reflection of their own patriarchal structures.

Browning’s genius was to withhold overt judgment. The Duke hangs uncondemned in the gallery of the reader’s mind—a lingering, disquieting presence. Victorian poetry had rarely shown such psychological penetration.

Porphyria’s Lover — Madness and the Erotics of Control

In “Porphyria’s Lover,” Browning pushed even further. On a stormy night, the speaker strangles his lover to preserve a moment of perfect union:

“That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good.”

The poem’s calm tone belies its horror. The speaker’s voice is chilling in its rationality—madness cloaked in domestic tranquility. Here again, Browning offers no moral frame; the reader is left alone with the speaker’s distorted consciousness.

In an era obsessed with respectability and self-control, Browning’s monologues forced a confrontation with the dark undercurrents beneath social order.

Fra Lippo Lippi and Andrea del Sarto — Art, Religion, and Human Frailty

Not all of Browning’s monologues are sinister. In “Fra Lippo Lippi,” the boisterous Renaissance monk debates the purpose of art:

“This world’s no blot for us,

Nor blank—it means intensely, and means good.”

Here is a vibrant affirmation of the sensuous world, in defiance of puritanical repression. Browning delights in Lippo’s earthy vitality, mocking the false asceticism of those who would deny life’s pleasures.

In “Andrea del Sarto,” by contrast, the aging painter speaks with weary self-awareness:

“Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what’s a heaven for?”

The line has become proverbial, but in context it is tinged with melancholy. Andrea, technically perfect, lacks the passionate soul that animates great art. Through him, Browning explores the tragedy of compromised ambition—a Victorian theme if ever there was one.

The Irony of Browning’s Optimism

It is tempting to view Browning as a cynical observer of human frailty. Yet in truth, he was an inveterate optimist, though of a deeply ironic cast. He believed in the value of struggle, the necessity of embracing life in all its contradictions. His philosophical outlook, influenced by Hegelian ideas of becoming, rejected static perfection in favor of dynamic imperfection.

His verse often celebrates the flawed striving of human beings. As he writes in “Rabbi Ben Ezra”:

“Grow old along with me!

The best is yet to be.”

Such lines resonated with Victorians seeking hope amid social upheaval and spiritual uncertainty.

A Private Public Voice

Unlike Tennyson, Browning never fully became the official voice of the Empire. His verse was too ironic, too challenging for broad ceremonial use. For many years, he remained a poet’s poet, admired by an intellectual elite rather than the general public.

Yet by the end of his life, his reputation had grown immensely. Victorian England had begun to appreciate the moral complexity and psychological depth of his work. In an age struggling to understand itself, Browning’s monologues provided a powerful tool for self-examination.

A Mirror for the Modern Mind

Browning’s true legacy lies not in grand public statements, but in his subtle demonstration that no human voice is entirely trustworthy, no utterance free of hidden motives. He taught Victorian literature—and by extension, modern literature—that character is constructed in language, and that poetry can reveal the shifting layers of the self.

In an empire that claimed moral superiority while practicing exploitation, Browning’s irony was a necessary corrective. His poems whispered what official rhetoric dared not say: that beneath progress lay unresolved contradictions, beneath virtue lay temptation, beneath order lay chaos.

As we turn now to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, we encounter another poet of the Victorian conscience—one whose voice would speak passionately for the voiceless, and whose verse would make the personal political. The age of doubt had also become an age of protest.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning — The Voice of the Conscience and the Heart

If Victorian poetry could be said to possess a moral conscience, much of it spoke through the voice of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

In an age when women’s roles were tightly confined and public activism was suspect in polite circles, her verse rang with a clear and fearless call for social justice, human compassion, and female agency. And yet hers was also a voice of profound personal feeling—fusing the political with the intimate in ways that helped redefine the potential of Victorian poetry.

Born in 1806 to a wealthy family, Elizabeth Barrett was a child prodigy—reading Greek by the age of eight, composing poetry by eleven. Yet her early life was clouded by chronic illness and a father whose patriarchal tyranny would haunt her for decades. Confined largely to her room, Elizabeth became a poet of vast imagination and fierce empathy—one whose awareness of suffering was sharpened by her own experiences of isolation.

The England into which she came of age was rife with hypocrisy and injustice. The Industrial Revolution had birthed both unprecedented wealth and crushing poverty. Child labor, slavery, and the widespread exploitation of the working poor coexisted with the pious rhetoric of Victorian morality. Few poets dared confront these contradictions directly. Elizabeth Barrett Browning did.

The Cry of the Children — Poetry as Protest

Her landmark poem “The Cry of the Children” (1843) emerged from a scandal that exposed the appalling conditions faced by child workers in British mines and factories. The poem became a rallying cry for reform:

“Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?”

These opening lines, simple yet devastating, stripped away the moral blinders of Victorian complacency. No mythic allegory here—just the stark, unadorned suffering of real children. The poem ignited public debate and helped galvanize support for labor reforms.

In using poetry as direct social intervention, Barrett Browning defied the prevailing belief that verse should concern itself only with the beautiful or the eternal. For her, poetry must be also an instrument of moral conscience.

Aurora Leigh — The Woman Artist’s Struggle

Yet Elizabeth Barrett Browning was no mere polemicist. Her verse novel Aurora Leigh (1856) remains one of the great feminist texts of the nineteenth century. Through the fictional voice of Aurora, a woman determined to become a poet on her own terms, Barrett Browning explored the constraints placed upon female ambition:

“The works of women are symbolical.

We sew, sew, prick our fingers, dull our sight,

Producing what? A pair of slippers, sir,

To put on when you’re weary.”

These lines drip with irony and suppressed rage. The poem charts Aurora’s journey toward artistic self-realization—a bold statement in an era when women were expected to choose domesticity over creativity.

Aurora Leigh was both a personal manifesto and a public challenge—urging women to claim their place not only in literature, but in the broader cultural and moral debates of their time.

Sonnets from the Portuguese — Intimate Love, Universal Resonance

While her public voice rang out for justice, Barrett Browning’s poetry also plumbed the depths of personal love. Her marriage to Robert Browning, forged in defiance of her father’s forbidding control, became one of the great literary romances.

In her Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850), Barrett Browning transformed personal passion into universal lyric expression. The most famous sonnet begins:

“How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

This line, oft-quoted to the point of cliché, retains its original force when read within the full arc of the sequence—a woman’s declaration of self-affirming love against a background of personal suffering and societal constraint.

In these sonnets, Barrett Browning achieved what few Victorian poets managed: a fusion of the intimate and the eternal, the personal voice raised into a public art that spoke to millions.

A Life of Quiet Defiance

Throughout her life, Elizabeth Barrett Browning remained both physically frail and morally fierce. Her verse championed not only child labor reform but also abolitionist causes, earning her admiration in both Britain and America.

Yet she refused to be drawn into easy ideological positions. Her poetry is marked by a deep awareness of the complexity of moral action and the limits of idealism. She neither romanticized the poor nor demonized the privileged. What she demanded, above all, was human empathy—a rare and vital force in the rigid social structures of Victorian England.

Legacy of the Conscience

Elizabeth Barrett Browning helped enlarge the moral scope of Victorian poetry. She demonstrated that verse could confront urgent social questions without sacrificing artistic integrity. In her hands, poetry became a space where the personal, the political, and the spiritual coexisted—each deepening the other.

Her example also opened new pathways for women writers. In speaking as a woman, for women, and for all who suffered injustice, she challenged both literary convention and social hierarchy.

As we turn next to Matthew Arnold, we shall encounter a different voice of the Victorian conscience—one less impassioned, more reflective, but no less aware of the age’s profound discontents. From moral protest we move to cultural diagnosis: the age of faith was giving way to an age of anxious introspection.

Matthew Arnold — The Victorian Mind in Crisis

If the Victorian Age had a poet who perfectly embodied its spiritual crisis, it was Matthew Arnold.

No other voice in mid-century English poetry so fully captured the era’s restless intellectual disquiet, its longing for faith amidst doubt, its fear that beneath the march of progress lay the slow erosion of meaning itself.

Born in 1822, the son of the famed headmaster Thomas Arnold of Rugby, Matthew Arnold was steeped from childhood in an environment of high moral seriousness and classical learning. Yet he came of age in a world where those very ideals were crumbling. The rise of scientific rationalism, the spread of materialist philosophy, and the cold indifference of the industrial world all conspired to undermine the Victorian ideal of moral certainty.

Arnold’s poetic career was relatively brief compared to Tennyson’s or Browning’s, but the depth of his insight and the haunting clarity of his verse ensured his lasting influence. For Arnold, poetry was not mere ornament or escape. It was, as he famously declared in his critical writings, “a criticism of life”—a medium through which the modern mind could confront its deepest uncertainties.

Dover Beach — Faith in Retreat, Eternal Melancholy

Nowhere is Arnold’s vision more poignantly expressed than in his great lyric “Dover Beach.” Standing at the shore, gazing across the moonlit waters of the English Channel, the speaker hears not the music of creation, but a “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar”—the Sea of Faith retreating from the world:

“The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar.”

This is the Victorian crisis of faith distilled into a single unforgettable image. The certainties of the past have ebbed away, leaving behind an exposed and vulnerable human spirit.

Yet Arnold does not end in nihilism. His closing plea is one of stoic humanism:

“Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.”

In a universe bereft of metaphysical comfort, human fidelity becomes the last refuge. The poem resonates with a deep modernity, anticipating the existential anxieties of the twentieth century.

The Scholar-Gipsy and Thyrsis — Nostalgia and Lost Wisdom

Arnold’s engagement with the modern world was marked by an aching nostalgia for lost wisdom. In “The Scholar-Gipsy,” he evokes the legend of an Oxford scholar who abandons the academic life to seek a purer, deeper knowledge among the gypsies. The poem is both an elegy for lost traditions and a subtle critique of the modern intellect’s sterile rationalism.

“But fly our paths, our feverish contact fly!

For strong the infection of our mental strife,

Which, though it gives no bliss, yet spoils for rest.”

Here, Arnold identifies the malaise of the modern mind: endless questioning without the peace of belief.

In “Thyrsis,” a pastoral elegy for his friend Arthur Hugh Clough, Arnold laments the loss of poetic innocence and communal faith. The beautiful yet mournful landscape of Oxford becomes a metaphor for the intellectual dislocation of the age.

Arnold’s vision is not reactionary—he does not call for a return to medieval certainties. Rather, he mourns the absence of a unifying cultural ethos in an age of fragmented knowledge and unchecked materialism.

Critic of Culture

Arnold’s significance lies as much in his prose criticism as in his poetry. In essays such as Culture and Anarchy, he argued passionately for the necessity of high culture as a counterbalance to both philistinism and narrow religious dogma. He warned that an unchecked industrial civilization would breed not progress, but a “vulgarized” society devoid of inner life.

“Culture,” he wrote, “seeks to do away with classes; to make the best that has been thought and known in the world current everywhere.”

This was not the elitism of a detached intellectual, but a genuine plea for cultural renewal—for the nurturing of an educated, morally serious citizenry in an era increasingly driven by commerce and mechanization.

Arnold was deeply aware of the limits of both religious orthodoxy and scientific positivism. He sought a middle ground, where the enduring wisdom of the past might inform the challenges of the present. In this, he became not merely a poet or critic, but a moral guide for a bewildered age.

The Victorian Mind in Crisis

Through both his verse and his prose, Matthew Arnold articulated the profound spiritual and cultural anxiety of mid-Victorian England. He stood at the intersection of tradition and modernity, seeking neither to deny the new nor to abandon the old.

In an empire that boasted of its material achievements, Arnold reminded his contemporaries—and us—that wealth and power cannot compensate for the loss of meaning. His poetry asks the deepest of Victorian questions: How shall we live when faith no longer sustains us, and reason offers no comfort?

Enduring Relevance

Matthew Arnold remains one of the most modern of Victorian poets. His voice, tinged with melancholy yet striving for dignity, speaks powerfully to our own age of technological triumph and spiritual uncertainty.

As we prepare to survey the broader field of early Victorian poetry beyond its central figures, we see in Arnold a figure who both summarized and transcended the anxieties of his time. The scholar, the skeptic, the poet—Arnold reminds us that even in the absence of certainty, the quest for wisdom and beauty must continue.

The Pre-Raphaelite Poets: Art, Beauty, and the Longing for a Lost Ideal

A Deeper Reflection on the Poetic Spirit of the Brotherhood

The Victorian Age was an age of iron and steam, of progress and anxiety, of moral fervor and spiritual erosion.

By the mid-19th century, England stood astride a vast empire, its industries reshaping the landscape, its faith shaken by the cold certainties of science. Amid this thunderous advance, a quieter but equally profound aesthetic revolt began to stir—not in the halls of Parliament, nor in the pulpits of Church, but in the studios of painters and the lines of poets.

This was the birth of the Pre-Raphaelite movement—a yearning not for new machines or fresh conquests, but for art that could rekindle the lost intensity of the human spirit.

Founded in 1848, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) began as a painter’s rebellion. Its members—Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, among others—declared war on the lifeless conventions of Victorian academic art, which they saw as having grown sterile under the shadow of Raphael and his followers. They sought a return to the vivid colors, spiritual sincerity, and symbolic depth of early Renaissance art—art before Raphael had smoothed its edges and clouded its soul with mannered idealism.

Yet from the very start, the Pre-Raphaelite vision was more than visual. It was deeply literary—a movement that saw painting and poetry not as rival arts, but as twin vessels for the eternal longings of the human heart. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the charismatic axis of the Brotherhood, was as much poet as painter. His literary instincts shaped the PRB’s broader philosophy: a belief that beauty was not merely decorative, but a doorway to deeper truths.

Their revolt was also against the moralizing tone of much Victorian literature. Where the age’s dominant poetry sought to instruct or comfort, the Pre-Raphaelite poets sought to enchant—to revive a world of intense sensory experience, where each image shimmered with symbolic resonance, each word rang with layered meaning.

Their poetry gleams with rich visual texture: the glow of stained glass, the perfume of unseen flowers, the cool weight of marble, the warmth of flesh, the icy touch of death. But beneath this surface splendor runs a deeper current: an aching sense of transience, a longing to preserve what the ravages of time inevitably consume.

Christina Rossetti, sister to Dante Gabriel, emerged as perhaps the Brotherhood’s purest poetic voice. Hers is a verse of haunting clarity, where spiritual devotion collides with the world’s sensual allure. In poems like Goblin Market, she wove fairy-tale enchantments into sharp allegories of female agency and Victorian hypocrisy. In her devotional lyrics, she charted the wrenching path between earthly attachment and heavenly aspiration.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s own poetry, particularly in The House of Life, burns with a more unabashed sensuality. His sonnets exalt the power of physical beauty even as they mourn its inevitable fading. Love in Rossetti’s verse is not mere sentiment—it is an act of worship, but one forever shadowed by mortality:

“Beauty like hers is genius.”

“She is a poem and shall not pass away.”

This tension—between the temporal and the eternal, between body and spirit—defines much of Pre-Raphaelite poetry. The poets sought not to deny the flesh, as did so much of Victorian piety, nor to embrace it blindly, as would later Decadents, but to celebrate its momentary brilliance while acknowledging its passing.

Other voices enriched this aesthetic chorus. William Morris, a close associate of the Brotherhood, brought medieval craftsmanship and socialist idealism into the movement. His poems and prose dreamt of a world where beauty and labor were harmonized, where artisans could reclaim the spiritual dignity lost to industrial mass production.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, though a more ambivalent figure, absorbed the Pre-Raphaelite ethos and pushed it to provocative extremes. His verse reveled in linguistic music and erotic intensity, challenging the narrow moral codes of Victorian society with defiant sensuality and pagan imagery.

Yet for all its variety, the Pre-Raphaelite poetic spirit remained unified by one central creed: a refusal to treat art as sermon or decoration alone. Poetry, for these writers, was a means of approaching mystery, of glimpsing truths that logic could not articulate.

They rejected the utilitarian spirit of their time—the belief that art must serve industry, politics, or dogma. Instead, they reclaimed the right of art to dwell in beauty, ambiguity, and longing. This made them pioneers of the Aesthetic Movement that would follow, and precursors to many strands of Modernist experiment.

Yet they were no idle dreamers. Beneath their nostalgia for lost medieval wholeness lay a keen awareness of their own moment: a recognition that Victorian England’s progress had come at the cost of spiritual depth. In response, their poetry offered moments of intense stillness, where beauty is beheld fully, even as it slips away.

“Look in my face; my name is Might-have-been.”—Rossetti’s chilling line captures the aching sense of what the modern world was losing, even as it raced forward.

Today, the Pre-Raphaelite poets remind us that in an age of relentless innovation, there remains a deep human need for mystery, for sensuous beauty, for symbols that speak to the soul as well as the mind.

Their work stands as a luminous testament to art’s power to transfigure the ordinary, to make fleeting things eternal, if only for a moment.

As we turn now to Christina Rossetti’s crystalline lyrics, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sumptuous sonnets, and their poetic kin, we step into a realm where art is neither sermon nor escape—but an act of remembrance, a fragile bridge between this world and what might lie beyond.

Other Significant Poetic Voices of the Early Victorian Age

No single voice can speak fully for an age as complex as the Victorian.

While Tennyson mourned and celebrated empire, Browning dissected the human psyche, Arnold questioned the withering of faith, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning fought for moral justice — many other poets, now sometimes overshadowed, wove vital threads into the larger tapestry of Victorian poetry.

Their works, though varied in form and vision, reveal the richness and contradictions of an age caught between hope and doubt, tradition and change.

Arthur Hugh Clough — Restless Intellect, Reluctant Faith

Arthur Hugh Clough stands as one of the most deeply modern of Victorian poets, even as he struggled with the same moral uncertainties that haunted Arnold, his close friend. Educated at Rugby and Oxford, Clough abandoned an academic career and the High Anglican orthodoxy of his youth, driven by a restless, inquiring spirit.

His verse is marked by a tone of uneasy irony—a refusal to embrace easy consolation. In his long poem “Dipsychus,” Clough voices the torment of a divided self, pulled between materialism and the fading echo of religious faith:

“Thou shalt not have been born in vain.”

The line, simple yet unresolved, captures the central dilemma of the Victorian mind: how to find meaning in a universe where traditional belief no longer sufficed.

Clough’s influence is profound not because he offered solutions, but because he dared to articulate the raw confusion of his time—a modern poet before modernism.

Coventry Patmore — Domestic Ideals and Victorian Orthodoxy

At the other end of the poetic spectrum stood Coventry Patmore, whose verse epitomized the Victorian cult of domesticity. His sequence “The Angel in the House” celebrated the idealized role of women as gentle moral guardians of the home—a vision deeply resonant with the era’s middle-class values.

“Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure.”

These lines, troubling to modern readers, reflect the pervasive belief in separate spheres for men and women—a belief that both confined and ennobled the Victorian ideal of femininity.

Yet to dismiss Patmore entirely would be unjust. His verse, though steeped in orthodoxy, is marked by genuine feeling and an often lyrical grace. He speaks for a large constituency of Victorians who, in a world of dizzying change, sought solace in the imagined stability of home and hearth.

A Chorus of Diverse Voices

Beyond these figures, many other poets contributed to the rich diversity of early Victorian verse:

James Thomson (not to be confused with the earlier poet of The Seasons) anticipated modern pessimism in “The City of Dreadful Night.”

William Allingham preserved the lyric traditions of Irish folklore.

Sydney Dobell and the Spasmodic School experimented with intense personal expression, though often derided by critics.

Together, these poets form a chorus of voices, each grappling with the age’s central tensions: faith vs. doubt, beauty vs. utility, self vs. society, tradition vs. change.

Toward the Future

By the late 1860s, the landscape of Victorian poetry had grown both richer and more fragmented. The certainties of the early century had given way to a more questioning, diverse poetic field.

Tennyson’s stately cadences, Browning’s penetrating monologues, Arnold’s cultural lament, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s moral passion—all had opened new paths. The voices of Clough, Patmore, Christina Rossetti, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti further expanded the poetic imagination.

Yet even greater shifts lay ahead. The coming decades would witness the rise of Aestheticism, Decadence, and new forms of spiritual rebellion—forces that would challenge the very foundations of Victorian moral and aesthetic ideals.

The early decades of Victorian poetry form a vast, resonant field—a landscape where voices of grandeur, doubt, protest, and longing intertwine.

In Tennyson, the age heard its public conscience, striving to uphold faith amidst the shadows of science and empire. In Browning, it confronted the unsettling depths of human motivation and the dark ironies of character. Through Elizabeth Barrett Browning, poetry became a clarion call for justice and compassion, while Matthew Arnold gave haunting voice to the spiritual crisis of an empire growing rich but inwardly impoverished.

Around these central figures, a constellation of poets—Arthur Hugh Clough, Coventry Patmore, Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and others—added notes of restlessness, piety, sensuality, and aesthetic daring. Their works remind us that the Victorian Age was never a monolith of certainty, but a realm of contested meanings, a culture searching for new forms to replace the lost grandeur of tradition.

As we close this first movement of the Victorian literary scroll, we sense the poetry of the age already straining toward new horizons. The lyrical confidence of Tennyson, the intellectual fervor of Browning, the moral urgency of Barrett Browning, and the cultural introspection of Arnold have prepared the stage for the next act—one where the novel, rather than verse, will take center stage.

In the pages that follow, we shall witness how the Victorian novelists—from Dickens and Eliot to the Brontës and Thackeray—crafted a new art of social vision, weaving stories that would capture the heart, mind, and conscience of an age.

The poet has sung. Now the storyteller shall speak.

Professor’s Note

This first part of our Victorian scroll reminds us that poetry, even in an age of steel and steam, remained the crucible of the English spirit.

The poets we have encountered were not relics of a vanished Romantic dream, but vital voices engaged with the deepest questions of their time—questions that, in truth, remain our own.

As we proceed to the second part of this scroll, let us remember: every age that prides itself on progress must also listen to its poets—who alone can tell us what we are losing in the pursuit of gain.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance