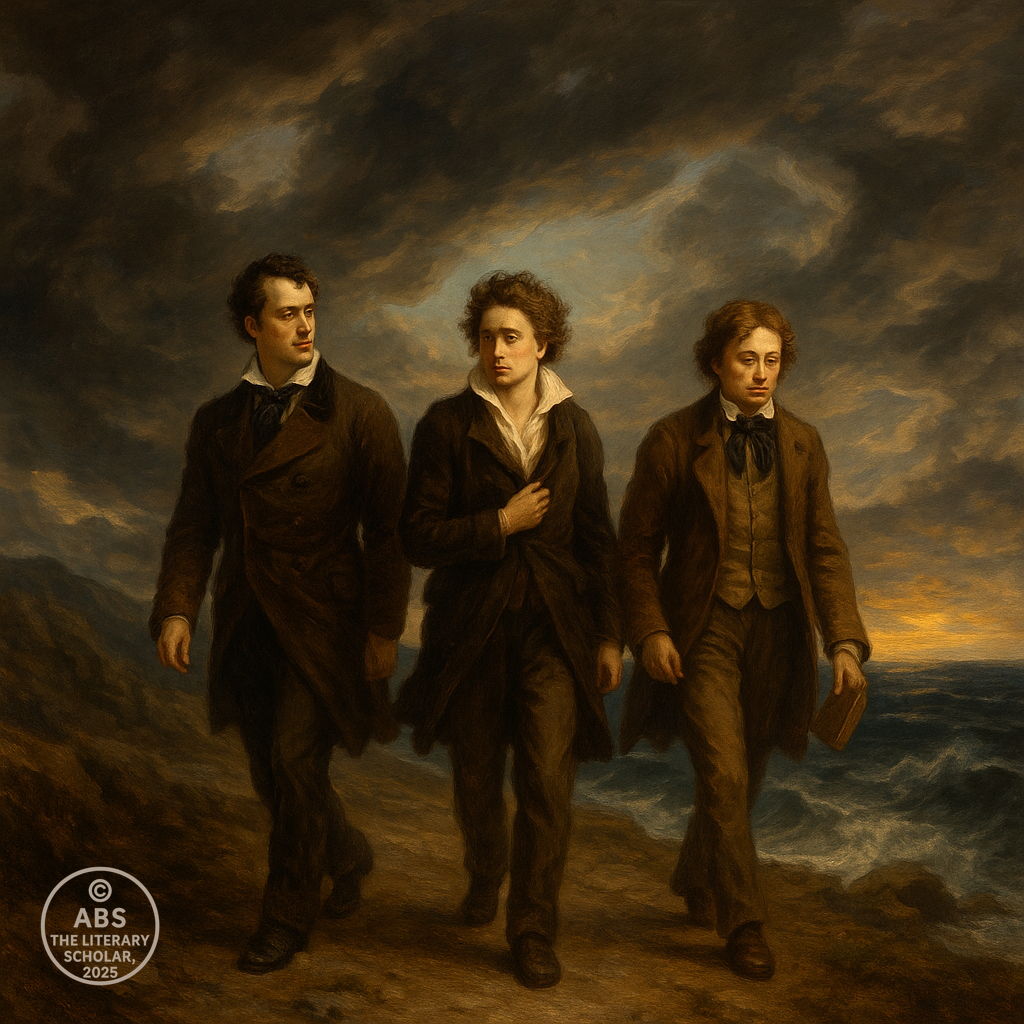

Byron, Shelley, Keats — the poetic rockstars of their age, who defied convention, embraced passion, and left behind verses that outlived their short, blazing lives.

From The Professor's Desk

The story of the Romantic movement is not a gentle stream — it is a river that gathers force, carves new channels, floods its banks, and leaves behind a changed landscape. If the Senior Romantics — Wordsworth, Coleridge, Southey — had brought this river back to its ancient, natural course, grounding poetry once more in Nature, in the common human heart, and in the rhythms of the eternal world, the generation that followed would stir it into a tempest.

The dawn of the Younger Romantics was a darker, stormier hour in the life of this river. The tranquil hills and wandering clouds of Wordsworth’s England gave way to a Europe haunted by revolution, betrayal, and the creeping realization that human history is written not only in green leaves and lyric song, but also in blood, smoke, and shadow.

It is no accident that the very atmosphere of Gothic art — of stormy castles, of forbidden loves, of wandering exiles and broken heroes — was the dominant cultural mood when Byron, Shelley, and Keats came of age. They were children of a world where the French Revolution had failed, where Napoleon’s glory had turned to ruin, and where the promises of liberty and reason had given way to repression and cynicism.

In this world, the Gothic was not mere fashion — it was the truest mirror of the age’s anxieties and longings. And into this Gothic night stepped the Younger Romantics — poets who would not only embrace the dark beauty of their time, but transform it into something immortal.

Their poetry was no longer a tranquil conversation with Nature, but a wild cry in the storm. They sought to give voice to the unruly passions, the unfulfilled desires, the political rage, and the existential fears of a generation that had seen the collapse of one dream and the harsh rebirth of another.

“She walks in beauty, like the night…”

“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being…”

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

In these immortal lines, we hear the very timbre of the new Romantic voice — not the steady hymn of the Senior Poets, but the reckless melody of those who knew they were writing against time itself.

Their lives would be as brief as their verses were lasting. Byron, Shelley, Keats — each would burn fast and fall young, leaving behind a body of work whose depth and daring belied their years. They were not poets of the hearth and home — they were wanderers, exiles, and sometimes fugitives, whose ink was mixed with desire, grief, and an unyielding pursuit of the sublime.

And all of this unfolded in a literary world saturated with the Gothic imagination — in which dark castles, windswept cliffs, forbidden loves, and the spectres of the past haunted the page as surely as they haunted the poets’ own lives.

This is the landscape we now enter. The wild hearts who walked here did not seek to comfort; they sought to transform. And they succeeded — not only in poetry, but in shaping the very myth of what it means to be a poet.

Let us follow them now — into the storm.

The Wild Ones Step In: The Shift to Younger Romantics

The shift was palpable. One can almost hear the hinge of history creak open in the literary world of early 19th-century England. The Senior Romantics had looked to Nature and memory for salvation; they had sought harmony between the human spirit and the eternal rhythms of the earth. But the younger generation of poets inherited a different world — one of unfulfilled revolutions, political betrayals, and the creeping shadows of a modernity no longer in love with itself.

The wind had changed, and with it, the tone of English poetry. The next wave of Romantics were not interested in solitary shepherds or rustic cottages. They sought poetry that spoke to the storm in the soul — to the rage against injustice, to the longing for forbidden love, to the seductive call of the unknown.

And where better to house such poetry than in the Gothic imagination that had already swept through literature and art? The towering ruined castles, the moonlit moors, the secret passageways of Gothic novels resonated with a generation for whom beauty and terror had become inseparable.

One need only glance at the images these poets loved — Byron’s exiled wanderers, Shelley’s fallen angels, Keats’s haunted urns and fading autumns — to see how deeply Gothic shadows had fallen across their verse. The Enlightenment’s clean lines and the Pastoral’s gentle sun had given way to a darker aesthetic — one where beauty was tinged with dread, and where every fleeting joy seemed pursued by a spectre of loss.

“There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture on the lonely shore…”

— Byron

“Ode to the West Wind”and Ode on Melancholy do not praise a tranquil world — they tremble with the awareness that all beauty is transient, and that only through art can one attempt to seize what time will otherwise erase.

This was the era of the wanderer, the exile, the tragic rebel. Where Wordsworth had walked familiar lanes and conversed with humble rustics, Byron, Shelley, and Keats walked among the ruins of lost ideals, haunted by the wreckage of revolution, and seduced by the impossible dream of eternal beauty.

Consider the backdrop of their lives. The promises of liberty, equality, fraternity had ended not in a golden age but in guillotines, Napoleonic tyranny, and a re-entrenched European conservatism. The idealists of 1789 had grown old or cynical. The young Romantics of 1815 could not look to political hope with the same innocent gaze.

They looked inward — and into the shadowed corners of history and psyche.

The Gothic castle, in this sense, became more than a physical setting; it became a metaphor for the haunted mind. Within its crumbling walls, its secret chambers, its ancestral curses, the poets found a mirror for the conflicted modern soul — one that longed for freedom but remained chained to loss, one that yearned for love yet feared the cost of feeling too deeply.

“She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies…”

— Byron

Here is the Gothic atmosphere distilled — beauty in the darkness, the nocturnal radiance that is all the more alluring because it is framed by shadow.

This new Romanticism was not a rejection of the Senior Romantics — it was their transformation. The younger poets inherited the tools of Nature-worship, lyrical form, and philosophical reflection, but they wielded them in the service of a more urgent, more haunted, more dangerous vision.

Byron’s heroes were outlaws, often self-exiled, bearing the wounds of past sins and forbidden passions.

Shelley’s visions oscillated between the hope for human perfectibility and the awareness of deep structural injustice.

Keats’s odes were elegies to the unattainable — to a beauty that always hovered just beyond the grasp of mortal hands.

And across it all hung the mists of the Gothic imagination — the sense that the past was not past, that old sins echo still, that the very stones of the earth remember, and that beauty, when glimpsed, may just as easily wound as heal.

“No sooner had I spoken than a deep and heavy bell began to toll…”

Such was the mood in which the Younger Romantics composed — a mood where even the air seemed charged with foreboding and forbidden wonder.

Their public images reflected this shift. The Senior Romantics had been mocked as pedantic nature-lovers or philosophical dreamers. The Younger Romantics, by contrast, became celebrities, rebels, icons of erotic and political danger. They were loved, hated, whispered about — not merely poets, but cultural phenomena.

Byron was chased out of England under a cloud of scandal.

Shelley lived as a political exile, his radicalism unwelcome at home.

Keats, though gentler, faced bitter attacks from critics and the gnawing certainty of early death.

And yet, from this gothic crucible, their greatest works emerged. Their poetry did not shrink from the darkness — it embraced it, sang within it, and in doing so, created a new kind of lyricism: one that acknowledged both the beauty and the terror of existence.

In this new Romanticism, the poet was not a wise rustic bard, nor a detached philosopher — the poet was the haunted visionary, the one who had looked into the abyss and dared to sing of what he had seen.

And it is into this world — of shadow and song, of exile and ecstasy — that we now follow three of its brightest, and most tragic, voices.

Lord Byron: Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know

George Gordon, Lord Byron, strode into the second act of the Romantic movement like a dark comet blazing across the polite skies of English letters. If Wordsworth had walked among daffodils and Coleridge had ridden through the mariner’s haunted seas, Byron galloped into the public imagination as a living embodiment of the very tensions that gripped the era — beauty and corruption, nobility and ruin, liberty and despair.

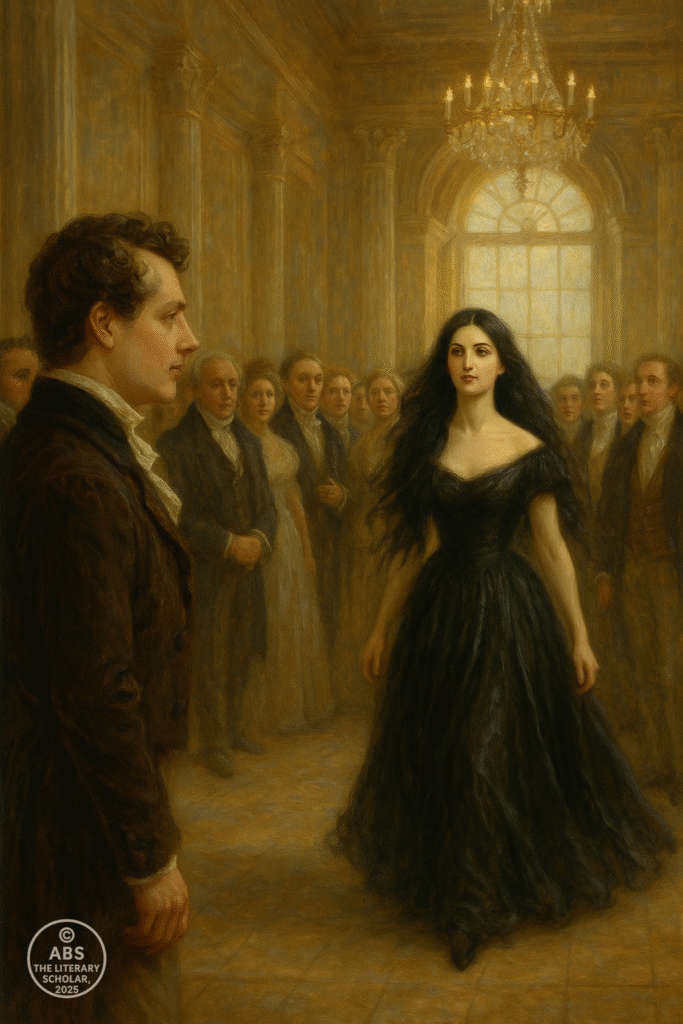

In a time when poets were still expected to be safe moral guides or at least respectable eccentrics, Byron’s arrival was a scandal. And Byron knew it — he cultivated it. When Lady Caroline Lamb famously described him as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” the phrase did not injure his reputation; it immortalized it.

Born in 1788 into a lineage marked by both aristocratic grandeur and personal disgrace, Byron inherited not only a title but also the full weight of a Byronic fate. A clubfoot in childhood left him with a lifelong sense of physical difference — a wound that fused with his literary temperament to produce one of the most enduring figures in modern cultural myth: the Byronic Hero.

Byron’s poetry, from the beginning, was never mere verse. It was an act of self-creation, a performance upon the stage of a Europe still reeling from the aftermath of revolution and the fall of Napoleon. His early triumph with Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage catapulted him to fame almost overnight.

“I awoke one morning and found myself famous,” Byron quipped — and the fame was not undeserved.

In Childe Harold, Byron gave voice to the profound disillusionment of his age:

“There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture on the lonely shore…”

The wanderer, alienated from a corrupt society, seeking solace in nature’s vast and indifferent beauty — this was not merely a poetic pose. It was Byron’s life, poured onto the page.

Yet if Childe Harold established Byron as the voice of a generation disenchanted, it was Don Juan that revealed the full measure of his genius.

In this sprawling, sardonic epic, Byron turned the legend of Don Juan inside out — presenting not a predatory libertine, but an innocent seduced by the hypocrisies of the world.

“But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling like dew upon a thought, produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think.”

Few poets could match Byron’s combination of wit, erudition, and moral cynicism — a style at once exhilarating and deeply unsettling. Through Don Juan, Byron exposed the rot beneath the glittering surface of European aristocracy — and in doing so, he ensured that no reader could ever again view romantic love, heroism, or virtue with naive eyes.

But Byron’s life was not confined to the page. In an era where celebrity as we understand it was just beginning to take form, Byron was its first true avatar. His affairs — particularly with Lady Caroline Lamb and the scandalous whispers surrounding his half-sister Augusta Leigh — turned him into a living symbol of forbidden passion.

Public scandal drove Byron into voluntary exile in 1816 — a departure that only deepened his myth. His journeys across Switzerland, Italy, and Greece became a new pilgrimage, and in each place, he wrote with an urgency born not of comfort but of spiritual restlessness.

In Italy, he composed some of his finest later work, including the savage cantos of Don Juan and the gothic drama Manfred — a Faustian meditation on guilt, power, and the limits of human striving.

“I am the very slave of circumstance

And impulse — borne away with every breath!”

The Byronic Hero — tormented, brilliant, self-destructive — was not a mere invention of fiction. It was Byron himself, refracted through the crystalline lens of poetry.

Yet Byron was more than a poetic self-dramatist. Beneath the scandal and irony lay a profound commitment to liberty. His final act, joining the cause of Greek independence, was no mere gesture. In Missolonghi, Byron risked his health and fortune for a people not his own, driven by the same fiery idealism that burned through his verse.

“Seek out — less often sought than found —

A soldier’s grave, for thee the best.”

In 1824, at the age of thirty-six, Byron succumbed to illness in Greece, never having seen the triumph of the cause he championed. But in death, as in life, he remained an outsider, a figure both revered and feared, admired and condemned.

The impact of Byron’s poetry and persona on the literary world cannot be overstated. He transformed the Romantic poet from a figure of gentle introspection into an icon of danger, sexual magnetism, and existential defiance. The Byronic Hero would stalk the pages of Victorian literature, from Heathcliff to Dorian Gray, from the Brontës to Oscar Wilde.

In Byron, poetry found not a moralist, nor a rustic dreamer, but a voice that dared to embrace the full spectrum of human desire and despair — a voice that whispered to the shadows even as it soared toward the stars.

His life was a poem too intense to last — a bright, burning scroll that still flickers with the dark fire of genius.

Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Idealist with Wings of Fire

If Byron embodied the dark glamour of the Younger Romantics — all defiance, sensuality, and tragedy — then Percy Bysshe Shelley was its purest flame — a restless spirit for whom poetry was prophecy, and whose words sought to liberate the world even as he remained forever an outsider within it.

Born in 1792 into a wealthy Sussex family, Shelley was destined for a life of comfort — a destiny he rejected with every fibre of his being. His time at Eton and Oxford revealed a mind unwilling to bow to orthodoxy. At just nineteen, he published The Necessity of Atheism, earning him swift expulsion and estrangement from his family. Thus began a life of voluntary exile, one which Shelley would transform into literary pilgrimage.

Unlike Byron, whose scandals drew public attention, Shelley’s exile was largely philosophical and political. He believed in the perfectibility of mankind, in the promise of revolution, in the innate goodness that society corrupts. His poetry was not about self-display but about vision — an urgent, burning hope that art might awaken humanity to its highest possibilities.

“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being…”

With this invocation begins one of the most iconic poems of English Romanticism — Ode to the West Wind. But what seems at first a lyrical homage to Nature is, beneath the surface, a revolutionary call. The West Wind becomes a symbol of the spirit of change, capable of sweeping away the dead leaves of tyranny and corruption, making way for new growth, new thought.

“Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither’d leaves to quicken a new birth!”

Shelley’s vision was not limited to political ideals. He longed for a cosmic harmony in which love, imagination, and reason would unite — a harmony he sought through both his poetry and his turbulent personal life.

His love for Mary Godwin — the future Mary Shelley — was one of the defining relationships of his life. Together they moved in a circle of fellow exiles, radicals, and visionaries — a circle haunted by poverty, infant mortality, and relentless public scorn. And yet from this hardship, Shelley’s most radiant verse emerged.

“Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert —

That from Heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.”

In To a Skylark, Shelley’s longing for transcendent song — for a voice untouched by human sorrow — becomes palpable. The Skylark is no mere bird; it is an embodiment of the ideal Shelley pursued his entire life — a beauty unsullied by pain, a song beyond the reach of time.

And yet, Shelley was acutely aware of the tragic limits of human existence. In Adonais, his elegy for Keats, we find a poet wrestling with both grief and acceptance:

“He is made one with Nature: there is heard

His voice in all her music, from the moan

Of thunder, to the song of night’s sweet bird.”

Here is the heart of Shelley’s philosophy — the belief that death does not extinguish the spirit, but returns it to the greater song of the universe. It is an idea both comforting and sublime — and one Shelley would soon test himself.

His longer philosophical drama Prometheus Unbound is a staggering vision of liberation — from tyranny, from fear, from the bondage of the human spirit. Through the myth of Prometheus, Shelley crafted a poetic manifesto for the Romantic imagination — one in which poetry itself becomes an act of revolution.

“To suffer woes which Hope thinks infinite;

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night;

To defy Power which seems omnipotent;

To love, and bear; to hope till Hope creates

From its own wreck the thing it contemplates.”

Yet Shelley’s life, for all its idealism, was marked by exile, tragedy, and premature loss. Financially ruined, politically isolated, and haunted by personal grief, he retreated ever deeper into the sun-drenched melancholy of Italy — a land whose classical ruins mirrored his own vision of a fallen, corrupt Europe, awaiting rebirth.

“Worlds on worlds are rolling ever

From creation to decay…”

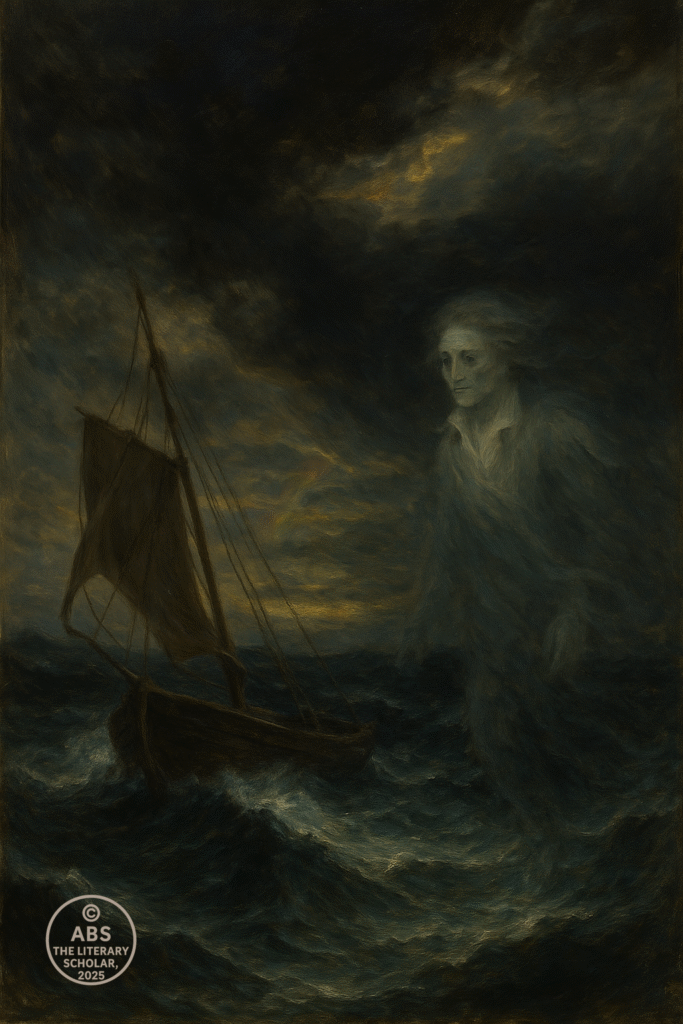

In 1822, Shelley set out on his final voyage — a literal one, aboard his schooner Don Juan. Caught in a sudden storm off the coast of Lerici, the poet drowned. When his body washed ashore, it was so disfigured that it could only be identified by a volume of Keats’s poetry found in his pocket — a final testament to the deep kinship between these two spirits of the Younger Romantics.

“Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

Shelley’s death was, in its own tragic way, a fitting sea-change — a transition from the frail mortal body to the enduring myth of the idealist poet. His verse remains a clarion call for those who believe that art must speak to the soul’s highest yearnings, that poetry must dare to dream of freedom, beauty, and truth — even if the world is not yet ready to receive them.

In Shelley, the Romantic movement found its purest visionary voice — a voice that still sings, wild and unbowed, in the winds of time.

John Keats: Beauty, Truth, and the Fragile Genius

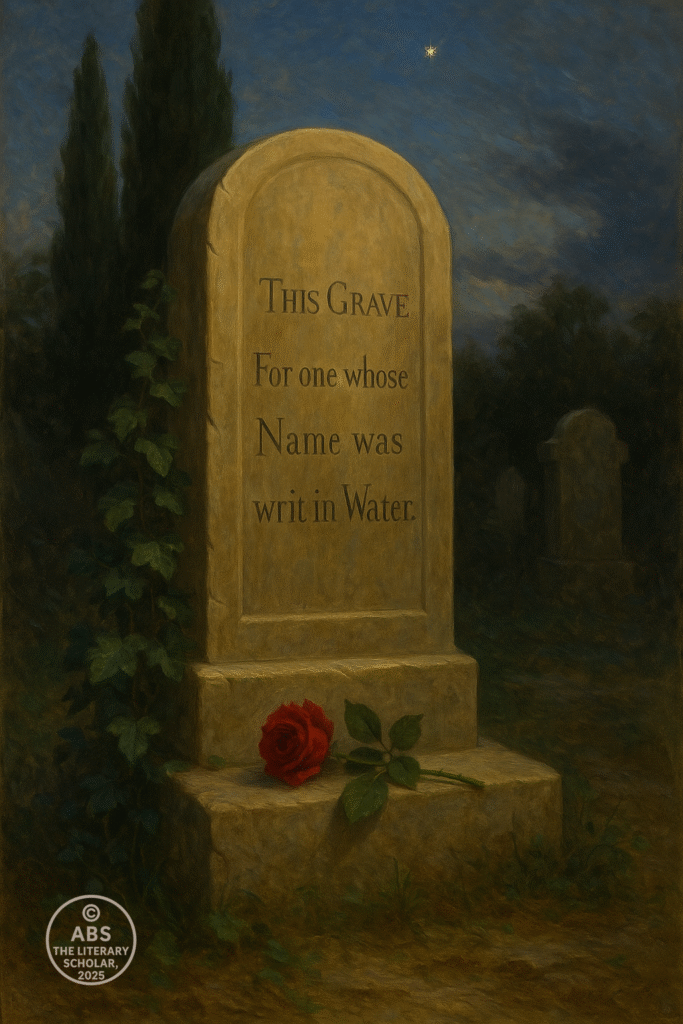

Of all the voices that rose during the tumult of the Younger Romantics, none sang with more poignant clarity than that of John Keats. His life was a brief, burning arc across the Romantic sky — a poet whose name was, in his own words, “writ in water,” yet whose verse endures as one of the most luminous legacies in English literature.

Born in 1795 to a stable-keeper’s family, Keats’s early life was marked by loss. His father died when Keats was eight; his mother succumbed to tuberculosis soon after. The shadow of mortality that would haunt his poetry had already shaped his boyhood.

Yet within this fragile frame burned an extraordinary spirit — a mind captivated by beauty, a heart attuned to the sublime melodies of language. Initially trained as a surgeon, Keats soon abandoned the scalpel for the quill. His decision was not a flight from reality, but a deeper embrace of it — for in poetry, he believed, one could confront life’s transient beauty with an intensity no other art could match.

“When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain…”

Keats was always writing against time. From the outset, he sensed that his own days were numbered — that consumption, which had claimed his mother and would claim his brother, was stalking him as well. This awareness gave his poetry a fierce urgency, an aching desire to capture what life might deny.

In 1819, at the age of just twenty-three, Keats composed a series of odes that remain among the greatest achievements of lyric poetry. In them, he distilled a philosophy as profound as it was poignant — that beauty and truth, though fleeting, are worth the fullest devotion of the soul.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

In Ode on a Grecian Urn, Keats contemplates the eternal scenes depicted on ancient pottery. The lovers frozen in time will never kiss, yet they are spared the pain of love’s fading. The pastoral pipes will forever play, though no mortal ear may hear them. It is a vision both beautiful and cruel — a reminder that art may capture what life cannot hold.

But Keats’s sensibility was not cold. His poetry is suffused with an intense sensuality, a reverence for the physical world in all its rich textures and sounds.

“Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun…”

In To Autumn, Keats offers not abstraction but a harvest of sensation — the warmth of ripening fruit, the hum of late bees, the hush of twilight fields. It is a celebration not of permanence, but of the present moment — fully felt, fully loved.

Yet beneath these rich images lies the deeper current of melancholy that defines Keats’s vision. In Ode to a Nightingale, the poet listens to the immortal song of the bird and longs to escape the burdens of mortal life:

“Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tramp thee down…”

Here is the essence of Keats’s genius — a mind that could perceive the eternal through the fragile lens of the moment. His poetry embraces life not by denying its transience, but by celebrating its fleeting beauty all the more intensely because it must pass.

Keats’s philosophy of Negative Capability — the ability to remain in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason — shaped his poetic voice. He refused to reduce life’s complexities to tidy moral lessons. Instead, he surrendered to the full depth of feeling, allowing beauty to speak for itself.

Yet even as his verse soared, Keats’s body failed. In 1820, his health collapsed. Ordered to the milder climate of Italy, he traveled to Rome with his devoted friend Joseph Severn. There, in a small apartment overlooking the Spanish Steps, he spent his final months in agony — physically wasted, emotionally tormented by his separation from Fanny Brawne, the woman he loved.

“I have been half in love with easeful Death…”

These words were no poetic affectation. Keats faced death with an unflinching gaze, aware that his dream of poetic immortality might die with him. His gravestone, chosen by the poet himself, reads:

“Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

And yet, the ironies of fate and art are sometimes kind. The name Keats feared would vanish like ripples on a pond has instead become one of the most cherished in English letters. His poems are not writ in water, but engraved in the hearts of readers who, across generations, return to them for solace, wonder, and a deeper understanding of what it means to be mortal and yet to aspire toward the immortal.

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”

And so it is with Keats’s verse — born from suffering, suffused with yearning, radiant with an understanding that beauty’s transience is what makes it all the more precious.

Among the Younger Romantics, Keats remains the most fragile, and the most universally beloved. He offers not the grand revolutionary visions of Shelley, nor the dark glamour of Byron, but a quieter, more personal testament: that to love beauty — fully, openly, even desperately — is to live most richly, no matter how short the span.

In every ripened fruit, in every passing song, in every line that trembles with the knowledge of its own impermanence, Keats’s spirit endures — fragile, brilliant, and eternally young.

The Younger Romantics and Their Enduring Impact

As the final pages of the Younger Romantics’ lives were turned — some closed abruptly, some trailing off into lingering shadows — a deeper truth remained: they had changed the landscape of English poetry forever.

The shift from the Senior Romantics to this younger generation was not merely a change in subject or tone. It was a revolution in the very purpose of poetry — a widening of the poet’s role from observer of Nature to prophet of the spirit, from recorder of rustic simplicity to chronicler of the soul’s deepest longings and society’s darkest failures.

If the Senior Romantics sought harmony with the natural world, the Younger Romantics grappled with a more chaotic universe — one where beauty, truth, and freedom had to be wrestled from the jaws of mortality and tyranny. They had seen the bright hopes of the French Revolution turn to ash; they had watched Napoleonic ambition crumble; they had lived in an age of political repression and social stagnation.

In this landscape, their poetry became not a pastoral retreat but a battlefield — where the forces of despair and hope clashed upon the poet’s own heart.

Byron gave voice to the alienated modern self — the rebel who walks alone, disillusioned yet defiantly alive. The Byronic Hero became a figure who would stalk the pages of literature long after Byron’s own mortal footsteps ceased. From Heathcliff to Dorian Gray, from the Romantic novel to contemporary cinema, this archetype owes its shadowed life to the dark brilliance of Byron’s verse and persona.

Shelley transformed poetry into a weapon of moral imagination — a medium through which the deepest ideals of liberty, justice, and universal love might find voice. His vision was not merely personal but cosmic, urging future generations to believe that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. In Shelley, we find the Romantic ideal of the poet as both dreamer and warrior for a better humanity.

And Keats — oh, Keats — offered the most timeless lesson of all: that beauty, however fleeting, is worth the cost of loving it; that truth, however painful, is worth the courage of seeking it. In his odes, we hear the most intimate voice of Romanticism — not grand, not prophetic, but quietly profound, teaching us to savour each moment’s fragile radiance.

“I have been half in love with easeful Death…”

That line — and so many others — still hum in the blood of every reader who dares to feel life deeply.

Yet the impact of the Younger Romantics was not limited to poetry alone. Their lives themselves became part of the mythos they helped to create. The Romantic cult of the tortured artist, the idea of the poet as outsider, as visionary, as martyr to truth and beauty — all crystallised in their brief, blazing biographies.

In doing so, they shaped not only the course of English literature but the very cultural imagination of the West. Without them, the great later movements of Victorian poetry, Symbolism, Modernism, and even postmodern art would lack their foundational spirit.

Where would the sensual lushness of Tennyson be without Keats?

The political passion of Yeats without Shelley?

The modern hero’s haunted solitude without Byron?

Even today, the ripple of their voices can be felt in every work that seeks to marry beauty with moral courage, art with rebellion, love with the knowledge of loss.

In their embrace of the Gothic imagination, they taught us that the shadows within us must not be denied but transformed into art. In their acceptance of life’s transience, they taught us that the fleeting can be made eternal through song. In their personal struggles, they taught us that greatness is often born from exile, from suffering, from the courage to stand apart from the complacent world.

Their impact endures because they spoke to truths that remain unchanged:

We long. We suffer. We love. We lose. We create.

And in the act of creation, something of us escapes the flow of time — something of us joins that immortal company of voices that, like the West Wind, continue to stir the leaves of history.

“Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither’d leaves to quicken a new birth!”

The Younger Romantics’ words still fly — across centuries, across minds — bearing their wild, beautiful flame into every new age of readers who dare to listen.

Their hearts burned too bright — but in their burning, they lit the path for all who would follow.

But the spirit of Romanticism did not die with these young hearts. If anything, it grew stronger — its echoes carried forward by the winds of poetry, prose, and imagination. For as their fragile lives slipped beneath the waves of time, their words remained — fierce, luminous, and defiantly alive.

And yet, poetry was no longer the sole vessel of the Romantic spirit. Beyond the sonnet and the ode, the age was giving birth to new forms — Gothic novels, philosophical essays, haunting tales — each infused with the very ideals that Byron, Shelley, and Keats had dared to voice.

We turn now to that unfolding story — where the quills of Romantic prose writers would sketch out new realms of shadow and wonder. The next scroll awaits.

The Professor folds this second scroll of the Romantic Era — where beauty, rebellion, and mortality entwined in words of eternal flame. The ink fades, but the music lingers on.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance