Red carpet entrance: Wordsworth and Coleridge, 1798 — Lyrical Ballads drops like a literary blockbuster.

From The Professor's Desk

There are moments in literary history when one age does not simply end and another begin — rather, the new age arrives walking upon a red carpet woven by its quiet forerunners. So it was in 1798. The Pre-Romantic poets — Thomson, Gray, Cowper, Burns, Blake — had already softened the ground beneath the heroic couplets and Augustan wit. They had taught poetry once more to speak from the solitary heart, to listen to Nature’s voice, and to trust the trembling note of personal feeling.

And then, like a long-awaited guest stepping into the ballroom, William Wordsworth walked in — not alone, but with Samuel Taylor Coleridge beside him. In their hands was a slim volume of poems called Lyrical Ballads — a book that would change English poetry forever.

This was no gradual evolution; it was a blockbuster release of the poetic spirit. If the Elegy in a Country Churchyard had taught us to mourn the unknown dead, Lyrical Ballads taught us to hear their living voices in the rustle of leaves, the murmur of brooks, and the cries of the common man. It was a shout-out to Nature, to emotion recollected in tranquility, to the infinite depths of the human soul.

The Pre-Romantic voices had whispered, “Feel.” Wordsworth and Coleridge now proclaimed, “Feel — and Speak!”

Behind them followed a generation of poets who would carry this revolution further — from the quiet Lakeland paths of the Senior Romantics to the flaming comets of Byron, Shelley, and Keats; from gothic prose to the subtle ironies of Austen. The Romantic Era was born not as a doctrine, but as a deep breath of the poetic spirit — long held, and now released.

It is to this rich and varied flowering that we now turn — and like the poets themselves, we begin our walk upon that red carpet of feeling.

The Red Carpet Moment — Lyrical Ballads and the Dawn of Romanticism

Poetic revolutions rarely arrive with clarion blasts. They arrive, more often, on quiet feet — or in this case, across a red carpet woven of fragile but persistent feeling. The Pre-Romantic poets — from Gray and Cowper to Burns and Blake — had already begun unfurling this carpet across the fields of English verse. They had whispered, sometimes with trembling voices, that poetry must once again feel, must once again touch the human heart.

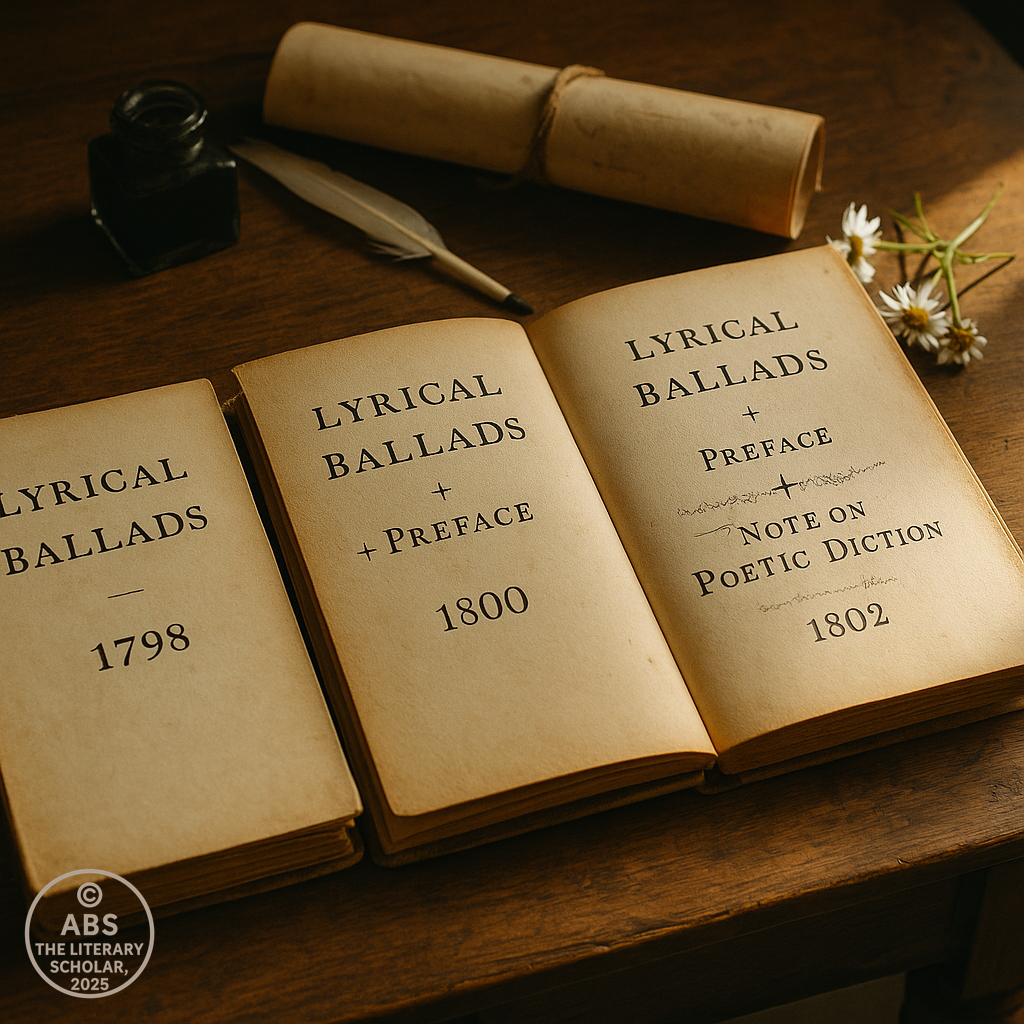

It was into this space that, in the remarkable year of 1798, two men walked: William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge — friends, collaborators, seekers of a new poetic vision. In their hands they carried a slim, almost unassuming volume: Lyrical Ballads. Yet this book would prove to be nothing less than a poetic manifesto — not through preface or polemic (that would come later), but through the simple yet profound act of poetic example.

If the Augustans had gilded their couplets with reason and decorum, Wordsworth and Coleridge laid their lines bare to Nature, to emotion recollected in tranquility, to the ordinary voices of men and women so long excluded from poetry’s hallowed halls.

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” These words, penned by Wordsworth in the later Preface to Lyrical Ballads, would come to define the very pulse of Romantic poetics. No longer was poetry to be the preserve of the clever or the elitely educated; it was to speak for and to the common man — in language that rang true to lived experience.

Why did this matter so deeply? Because English verse, for a century, had become the sport of the drawing rooms — a matter of wit, of satire, of exquisite form rather than of raw feeling. The heart had been dressed in elaborate finery; its honest voice had been muffled beneath the powdered wig of taste.

But Wordsworth and Coleridge changed this. Together, they offered a collection that celebrated not the king, the court, or the hero, but the solitary wanderer, the humble rustic, the ancient mariner adrift upon haunted seas, and the poet communing with a ruin-cloaked landscape.

The genius of Lyrical Ballads lay in its insistence that the commonest experiences, properly observed and profoundly felt, could be the stuff of great poetry. As Wordsworth declared:

“There neither is, nor can be, any essential difference between the language of prose and the language of metrical composition.”

This was a literary earthquake. Poetry was no longer to be written for poets alone. It was to become once more the song of humanity — rooted in the rhythms of everyday life, shaped by the timeless cadences of Nature.

And it is no accident that Nature herself stood at the heart of this revolution. For the Romantic poet, Nature was not a scenic backdrop — it was a living presence, a moral teacher, a force through which the poet might reconnect with lost innocence, with authentic feeling, with the deeper self that modernity had begun to estrange.

In this sense, Lyrical Ballads was a quiet but radical text. It did not shout its rebellion; it sang it in the voice of the woods and the water. It spoke of wanderers and beggars, of daffodils dancing beside lakes, of the ancient mariner’s curse and the redemptive wisdom gained through suffering.

At first, the literary world scarcely knew what to make of it. But in the years that followed — and especially with the famous 1800 Preface and the expanded 1802 edition, which included Notes on Poetic Diction — the volume would come to be recognized as the cornerstone of the English Romantic movement.

Poetry had been reborn. And the carpet on which Wordsworth and Coleridge had walked was now wide enough for a generation of poets to follow — each bringing their own voice, their own vision.

But before that next wave would rise, the two friends — along with their circle — would begin shaping the first great phase of this movement: the age of the Senior Romantics.

To this rich and varied company we now turn.

William Wordsworth — The Priest of Nature

When the literary history of an age is written, it is often the boldest, loudest voices that first command the eye. Yet the true revolutions are sometimes led by quieter figures — by those whose words, though spoken softly, change the very air that future voices will breathe.

William Wordsworth was such a figure. He did not seek fame through poetic acrobatics or political thunder. Instead, he sought to restore poetry to its ancient, sacred purpose: to speak to the human heart with honesty, humility, and grace — and through that speech, to heal a culture that had grown estranged from Nature, from feeling, and from its own spiritual core.

Wordsworth’s poetic creed was simple yet profound:

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.”

In this one sentence — drawn from his now-legendary Preface to Lyrical Ballads — lies the pulse of Romantic poetics. Emotion, not intellect, is the fountainhead of art. Yet that emotion must be shaped not in the heat of the moment, but in the cool clarity of reflection — when the mind, stilled by the passage of time, can give form to the deep currents of experience.

Prior to Wordsworth, English poetry had largely been a performance for the educated few. It glittered with wit, sparkled with satirical elegance, and often bent its knee to the classical ideals of decorum and taste. The poet was a figure apart, writing for his fellow craftsmen, weaving intricate verbal tapestries to delight the connoisseur.

But Wordsworth rejected this aristocratic vision. In his Preface, he wrote with unwavering conviction:

“There neither is, nor can be, any essential difference between the language of prose and the language of metrical composition.”

This was not a call to flatten poetry into mere prose, but a declaration that poetic truth must speak in the rhythms of real life, not in the artifice of elevated diction. The poet must not stand on a pedestal; he must walk among men, listening to their voices, sharing their joys and sorrows. In this new age, the poet wrote not for the poet alone, but for the common man — and through him, for the universal spirit that binds all humanity.

At the heart of Wordsworth’s vision stood Nature — not as a backdrop for human dramas, but as a living moral teacher, a presence through which man might recover the wisdom lost amid the smoke and noise of modern life. In an age of accelerating industrialization and alienation, Wordsworth held fast to the belief that the natural world still spoke a language the soul could understand — if only we would listen.

“Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.”

This was not romantic escapism. For Wordsworth, the communion with Nature was an ethical act — a way of restoring the moral imagination, of reawakening compassion, wonder, and gratitude. In poems such as Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, The Prelude, and the luminous Ode: Intimations of Immortality, he showed that the deepest truths were not found in the salons of the city, but in the quiet of woodlands, the murmur of rivers, the solitary gaze upon a field of flowers.

Who were his heroes? Not kings or warriors, but beggars and shepherds, solitary wanderers, children playing among lambs. These humble figures became, in his hands, symbols of universal experience — of joy, loss, resilience, and the simple dignity of life.

“The child is father of the man.”

With this line, Wordsworth distilled the Romantic faith that in the innocence of childhood lay the truest wisdom — a wisdom adults, blinded by pride and reason, often forgot.

Among his greatest achievements, Tintern Abbey stands as a towering testament to this vision: a poem that moves from the intensity of youthful sensation to the calm insight of mature reflection, weaving a meditation on memory, Nature, and the enduring ties of love.

“Though changed, no doubt, from what I was when first

I came among these hills…”

In such lines, Wordsworth speaks to us all — for who has not known this passage from youthful rapture to the quieter wisdom of age?

His Ode: Intimations of Immortality voices the great Romantic longing — the ache for a lost unity with the world, the sense that childhood grants us a fleeting vision of truth that later life obscures:

“Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting…”

And yet, for Wordsworth, this loss is not cause for despair. Through memory, through poetry, through the attentive love of Nature, we may yet recover glimpses of that vanished radiance.

In his Lucy poems, Wordsworth distilled this ethic into some of the purest lyric verse in English — poems of love, loss, and the fragile beauty of life, written with a restraint and sincerity that remain unsurpassed.

What, then, was Wordsworth’s true gift? It was to remind us that poetry begins where life is most real — in the heart’s deepest stirrings, in the textures of everyday experience, in the humble things we pass by unheeding.

Through his work, poetry ceased to be a performance for the privileged and became once more a song for all mankind — a song that teaches us, even now, to walk more gently upon the earth, to listen more closely to the voices of Nature and of the human heart.

It is no exaggeration to say that without Wordsworth, modern lyric poetry as we know it would not exist. He taught us that truth need not be shouted; it can be spoken in the quiet tones of sincerity, humility, and love.

Through his example, a new path was laid — and along it, the poets of his age, and those who followed, would walk with renewed purpose.

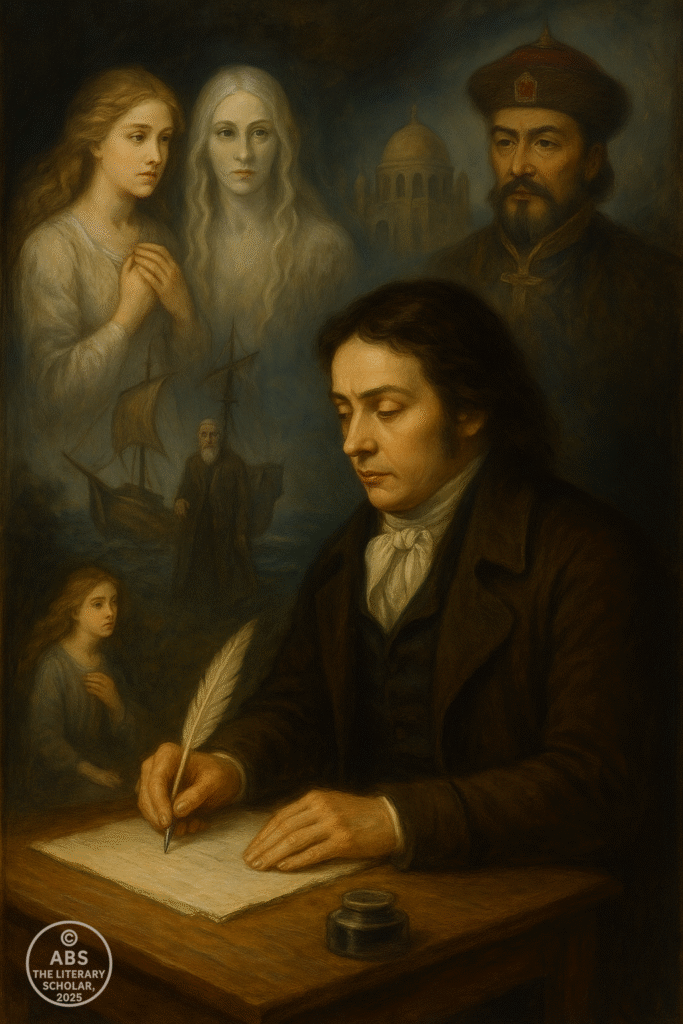

Samuel Taylor Coleridge — The Architect of Imagination

If Wordsworth brought poetry back to the earth — to Nature, to the voices of common men and women — then Samuel Taylor Coleridge lifted it once more toward the mysterious, the visionary, and the unknown. In the great architecture of Romanticism, Coleridge was not the stone mason but the designer of its haunted towers and secret chambers — the poet who taught us that the imagination is not a mirror of the visible world, but a lamp by which we glimpse its hidden depths.

In an age that hungered for reason and certainty, Coleridge insisted that some truths must be approached through dream and symbol — that the supernatural, far from being a childish fancy, was a language through which the psyche speaks its deepest fears and longings.

“The primary Imagination I hold to be the living power and prime agent of all human perception.”

With these words, Coleridge articulated one of the great insights of Romantic poetics: that Imagination is not an embellishment of reality, but the very means by which we apprehend it. Without imagination, the world would be a barren sequence of facts; with it, we glimpse wonder, beauty, and the ineffable mystery that underlies all things.

Coleridge’s life was as haunted as his verse. Born in 1772, he possessed from early childhood an extraordinary mind — voracious in its intellectual appetite, yet vulnerable to physical illness, emotional turmoil, and eventually, addiction to opium, which would both feed and fracture his poetic gifts.

His friendship with Wordsworth was one of the great creative partnerships in English literature. Together, they shaped the vision of Lyrical Ballads: Wordsworth grounding the movement in Nature and human feeling, Coleridge opening its doors to the supernatural and psychological realms.

“My endeavours were directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic.”

In poems such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Coleridge achieved a synthesis of ballad form, psychological depth, and moral vision that remains unmatched. What begins as a sailor’s tale of misfortune becomes a profound allegory of guilt, alienation, and redemption.

“He prayeth well who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.”

This closing line is no quaint moralism; it expresses the Romantic conviction that all life is sacred, and that to harm one part of Nature is to incur a spiritual wound.

In Kubla Khan, Coleridge ventured even deeper into the realm of pure imagination. Born of an opium-induced dream, the poem offers a vision not of moral allegory, but of the mind’s creative power itself.

“A stately pleasure-dome decree

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.”

Here, the pleasure-dome is more than an exotic structure; it is a symbol of artistic vision, of the transcendent beauty that the mind can briefly summon, though it may never fully possess it.

Kubla Khan is a fragment — but its very incompleteness speaks to the Romantic sense that imagination is always striving toward visions it cannot fully capture.

In Christabel, Coleridge explored another key Romantic theme: the ambiguous nature of evil and the haunting power of the unconscious. Through subtle imagery and musical language, he created a poem that leaves its readers uneasy — not because it explains, but because it awakens the shadowed regions of the psyche.

Beyond his poems, Coleridge’s critical writings in Biographia Literaria gave Romanticism its most sophisticated theoretical foundation. There, he distinguished between primary and secondary imagination — the first being the power by which we perceive the world, the second the creative power of the poet, who shapes perception into art.

“The secondary Imagination dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate.”

In these words lies the very heart of Romantic art: the belief that the poet must break through the surfaces of experience to reveal its deeper unity.

Yet Coleridge’s life was one of tragic tension. His intellectual brilliance was matched by a profound insecurity, and his addiction to opium cast long shadows over his later years. His friendship with Wordsworth, once so rich, became strained, though never fully broken.

But it is this very tension — between vision and failure, between ideal and reality — that gives Coleridge’s work its haunting power. He was the Romantic poet who understood that the greatest truths are those we glimpse, not those we master.

“What if you slept? And what if, in your sleep, you dreamed?

And what if, in your dream, you went to Heaven and there plucked a strange and beautiful flower?

And what if, when you awoke, you had the flower in your hand? Ah, what then?”

Through such questions, Coleridge invites us into a world where dreams matter, where symbols speak, and where poetry is not an escape from life, but a deeper engagement with its mysteries.

Without Coleridge, Romanticism would have lacked its dark splendour, its sense of the numinous, its faith in the transformative power of the imagination.

He was, and remains, the Architect of Imagination — a poet who showed that the true boundaries of art are not those of the visible world, but of the mind’s infinite longing for the unseen.

And yet the Lake District was not only a stage for great poetic voices — it was also a place where smaller, quieter presences shaped the larger currents of Romantic thought.

Among these presences, none was more significant than Dorothy Wordsworth.

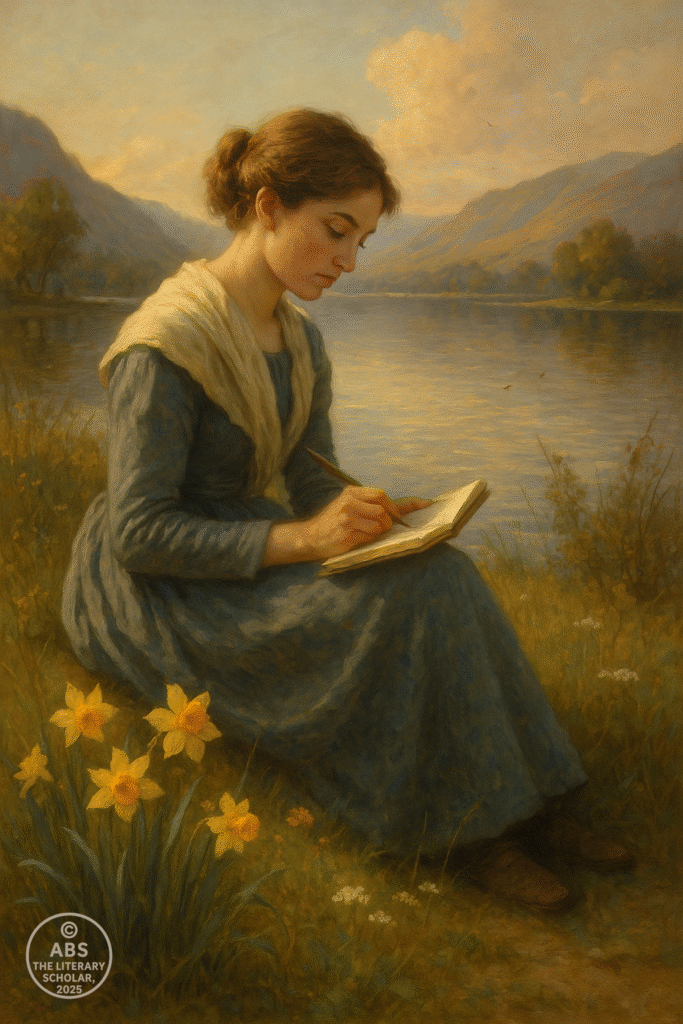

She published almost nothing during her life, and had no ambition to be known as a poet. But through her journals, her letters, and her daily companionship with her brother William, she became one of the hidden architects of the Romantic sensibility.

It was through Dorothy’s eyes that Wordsworth often came to see Nature in its most intimate details. Her gift was not for grand philosophical abstraction, but for the attentive noticing of the world’s small, transient beauties — the movement of clouds across a lake, the shifting light through spring leaves, the dance of daffodils in the breeze.

“I never saw daffodils so beautiful,” she wrote in her journal on 15 April 1802, after a walk along the shores of Ullswater. It was this entry that would later inspire her brother’s most famous poem, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.

But this was no act of passive transcription. Dorothy’s spirit of observation, her deep emotional responsiveness to the natural world, helped to shape her brother’s vision of poetry itself. Through her, Wordsworth learned to see that the smallest moment could carry infinite emotional resonance.

The great achievement of the Lake Poets was not simply to elevate the rustic or the humble into verse — it was to awaken a mode of attention that saw eternity in a grain of sand, the infinite in the passing of a cloud.

In this, Dorothy Wordsworth was a vital force — not as a maker of poems, but as one who taught others how to see, and in seeing, how to feel.

And it was this quality of seeing that gave the Lake School its distinctive tone.

Though Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey were often discussed together, they were not a formal school in the sense of shared doctrine or manifestos. What united them was something subtler: a shared belief that poetry must recover the immediacy of lived experience, that the deepest truths lie not in the abstractions of philosophy but in the felt textures of the world.

Yet among them, Robert Southey stood somewhat apart — a figure of prodigious industry, public ambition, and an evolving political conscience.

It is to his complex role in this circle — and in the wider Romantic era — that we now turn.

Robert Southey — The Minor Lake Poet

In every literary movement, there are figures whose presence is more solid than soaring — writers who may lack the intense flame of genius but provide the structural pillars upon which their more incandescent contemporaries lean.

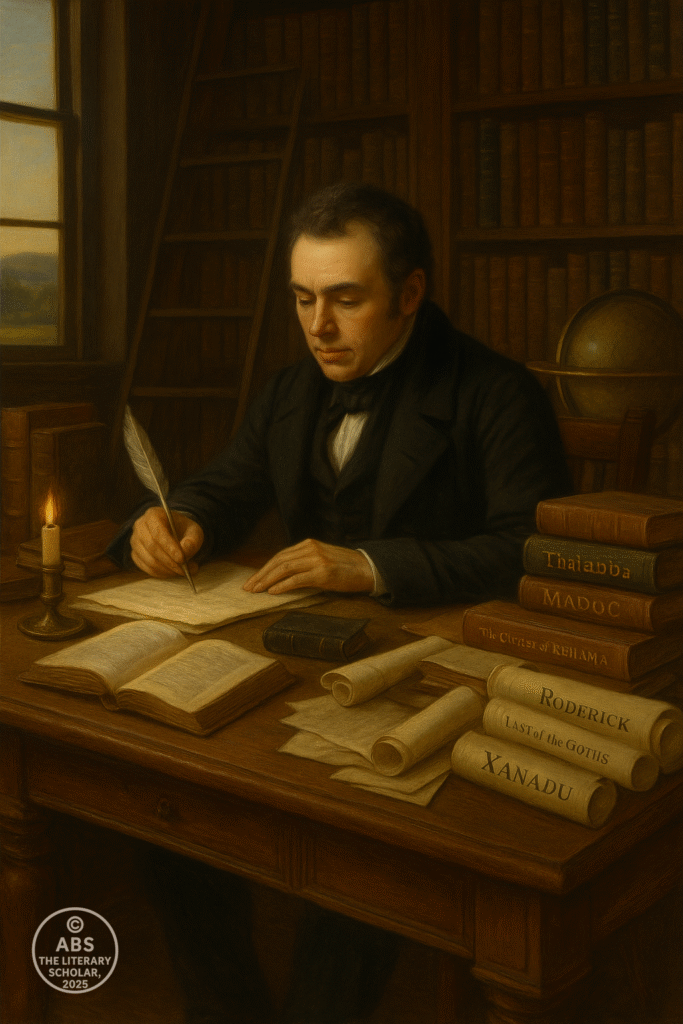

Among the Lake Poets, Robert Southey was such a figure. He was not a poet of the first rank — not a Wordsworth or a Coleridge — but he was a man of immense energy, boundless learning, and unflagging industry. If others captured the heights of Romantic vision, Southey ensured that the edifice of English letters remained broad, stable, and vigorously maintained.

Born in 1774, Southey was a contemporary of both Wordsworth and Coleridge, and an early fellow traveller in their youthful dreams of revolution and renewal. Together, they imagined the utopian scheme of Pantisocracy — a plan to found a communal society in America, where equality and brotherhood would reign. It was an idea born of idealistic fervour, and like many such dreams, it faded in the face of practical reality.

But where Wordsworth’s response to the collapse of revolutionary hopes led him inward — toward Nature and the moral life — and where Coleridge turned to the imagination’s visionary powers, Southey remained a man of the public world.

He became one of the most prolific writers of his age: poet, historian, biographer, essayist — a literary craftsman whose pen was rarely still. In time, he would be appointed Poet Laureate of England, a role he held for three decades.

Yet his poetic achievements, though numerous, are uneven. Southey possessed an admirable gift for narrative poetry, for the weaving of epic tales drawn from myth, legend, and exotic cultures. But his work often lacked the lyric intensity and emotional depth that mark the greatest Romantic verse.

“Thalaba the Destroyer,” “Madoc,” “The Curse of Kehama,” “Roderick, the Last of the Goths” — these epics reflect both Southey’s scholarship and his moral earnestness. Yet they sometimes strain beneath the weight of their own ambition, their diction more elaborate than immediate, their characters often vehicles for moral themes rather than living presences.

Still, it would be unjust to dismiss Southey’s contributions. In an age where narrative poetry was increasingly overshadowed by the lyric, he kept alive the epic tradition in English verse. His commitment to the moral function of poetry, though sometimes didactic, aligned with the Romantic conviction that art must serve truth and virtue.

Moreover, his prose writings — including biographies of Nelson and Wesley, histories of Brazil and the Peninsular War — displayed a clarity of mind and breadth of knowledge that few of his peers could match. In these works, Southey’s voice is at its strongest: balanced, judicious, and deeply informed.

His relationships with Wordsworth and Coleridge were complex. Southey admired Wordsworth’s poetry but could not always share his more mystical leanings. With Coleridge, the bond was one of friendship mingled with frustration — Southey respected Coleridge’s genius but lamented his lack of discipline and practical achievement.

Politically, Southey evolved from youthful radicalism to a more conservative stance — a shift that earned him both criticism and praise. As Poet Laureate, he defended the monarchy and Church of England, becoming, in the eyes of some, a symbol of the very establishment his younger self had once opposed.

Yet beneath this apparent conservatism remained the heart of a man who valued justice, honesty, and moral clarity. He may not have set the Romantic skies ablaze with vision, but he ensured that its more grounded virtues were not forgotten.

In the grand architecture of the Romantic movement, Southey is not the soaring spire or the luminous stained glass — he is the strong supporting pillar, the carefully laid stone. And every cathedral needs such stones, lest it collapse under the weight of its own dreams.

William Hazlitt — The Critical Voice of Romanticism

Every great literary movement requires not only poets and dreamers, but also witnesses and interpreters — those rare critics who do not merely explain art to the world, but who enter its spirit so deeply that their words become part of its unfolding life.

For the English Romantics, that voice belonged to William Hazlitt.

Hazlitt was not a poet — though he had trained first as a painter, and always brought a painter’s eye to the textures of language. He was not a man of grand philosophical systems, though he possessed a restless and often turbulent intellect. But as a prose stylist, a literary essayist, and the critical conscience of his age, he had few equals.

In Hazlitt’s essays, the Romantic movement found not a cheerleader, but a brilliant, passionate defender — one who grasped its deepest values and articulated them with a clarity and force that no manifesto could match.

“The love of Nature is the only love that does not decay with time.”

Such sentences are not merely critical observations; they are themselves acts of Romantic vision, distilling the movement’s spirit into crystalline prose.

Hazlitt’s life was marked by a continual striving after truth, sincerity, and authentic feeling — qualities he found too often lacking in the brittle conventions of Augustan verse. To him, the greatest poetry was not the most polished, but the most profoundly human.

“Poetry is the language of the imagination and the passions.”

In this conviction, Hazlitt stood shoulder to shoulder with Wordsworth and Coleridge, even as he sometimes critiqued them. He saw that the Romantic project was not a matter of fashion or style, but a profound attempt to restore depth, feeling, and vision to English letters.

His celebrated Lectures on the English Poets, delivered in 1818, remain one of the finest critical achievements of the era. In these lectures, Hazlitt championed the values of imagination, emotion, and individual vision — defending the Romantic spirit against those who would reduce poetry to formal correctness or intellectual cleverness.

At a time when Wordsworth’s plain style was still misunderstood by many, Hazlitt declared:

“The most original poet now living is Mr. Wordsworth.”

Such judgments required not only literary insight, but moral courage. Hazlitt was often a figure of controversy — a critic unafraid to speak uncomfortable truths, even at the cost of his own popularity.

His essays in Table Talk and The Spirit of the Age brought the same spirit to prose that the Lake Poets brought to verse: a commitment to sincerity, feeling, and the moral imagination.

For Hazlitt, criticism was not the cold dissection of art, but a living conversation with it — a way of entering into the emotional and imaginative world of the poet, and helping others to do the same.

He brought this spirit not only to his reflections on literature, but to his writings on Nature, politics, and the very experience of being alive. In essays such as On Going a Journey, Hazlitt revealed a soul attuned to the transient beauties of the world — a true Romantic wanderer in prose.

“Give me the clear blue sky over my head, and the green turf beneath my feet — a winding road before me, and a three hours’ march to dinner — and then to thinking!”

Here, the critic steps beyond the study and into the open world, embodying the very spirit of freedom and movement that defined Romantic art.

Yet Hazlitt’s life was not an easy one. His fierce independence, his unwillingness to flatter power or conform to fashion, often left him isolated. He suffered personal betrayals, professional disappointments, and periods of bitter poverty.

But through it all, he remained faithful to his vision — a vision in which art matters, because it speaks to what is most real and most enduring in human life.

Without Hazlitt, the Romantic movement might still have triumphed — but it would have done so with fewer allies, and with less clarity about its own deepest aims. He was the critic who gave Romanticism its critical voice, who defended its values when they were most misunderstood, and who showed that prose itself could be a Romantic art.

In the great symphony of this era, Hazlitt was not the soaring violin nor the thunder of drums — he was the deep resonance of the cello, carrying the movement’s undertones of passion, honesty, and moral force.

In Hazlitt’s essays, the Romantic movement found not a cheerleader, but a brilliant, passionate defender — one who grasped its deepest instincts even when its poets could not always articulate them themselves.

Born in 1778, Hazlitt came of age amid the same currents of political upheaval and artistic revolution that shaped Wordsworth and Coleridge. Yet his temperament remained fiercely independent. He believed in liberty, in the dignity of the individual mind, and above all in the power of authentic feeling over stale conventions.

“The love of Nature is the only love that does not decay with time.”

In such sentences — as compact as any great line of poetry — Hazlitt expressed the core Romantic faith that Nature speaks to something in us that neither the passing of years nor the corrosion of culture can erase.

His famous Lectures on the English Poets (1818) were more than an academic exercise; they were a call to re-enchant the literary imagination. In them, Hazlitt argued that poetry’s greatness lies not in its adherence to classical rules or its display of technical skill, but in its capacity to awaken the heart and imagination — to move us in ways no other art can.

“Poetry is the language of the imagination and the passions.”

Hazlitt understood that the Romantic revolution was not merely a change of style or subject matter. It was a return to the ancient purpose of poetry: to make us feel deeply, to connect us with the elemental truths of experience.

He was one of the earliest critics to defend Wordsworth’s radical simplicity — when many still dismissed it as artless — and to celebrate Coleridge’s visionary power, even as Coleridge’s own creative energies faltered.

But Hazlitt was not content to write about poets alone. In his essays collected in Table Talk and The Spirit of the Age, he ranged widely — on politics, on theatre, on painters, on the fleeting textures of everyday life. Always, his prose burns with a passion for truth, for beauty, and for the inner freedom of the mind.

“I hate everything mechanical and systematic.”

In this fierce declaration, one hears the authentic Romantic spirit — the insistence that art must arise from the living pulse of experience, not from the dead hand of formula.

Yet Hazlitt’s life was often one of struggle and alienation. His fierce independence, his political radicalism, and his blunt honesty earned him many enemies. He was often at odds with Wordsworth, whose later conservatism he deplored, and his relationship with Coleridge was a mixture of admiration and bitter disappointment.

But these personal rifts never dimmed Hazlitt’s critical insight. He remained one of the few voices of his time capable of articulating why Romantic poetry mattered — not as fashionable novelty, but as a profound renewal of the poetic soul.

He recognized that in the works of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and their peers, English literature had recovered something vital: a sense that poetry belongs not to the academy, nor to the court, but to the heart of every human being.

“If the child-like heart did not beat beneath the old cynical breast of manhood, there could be no poetry.”

It is through such insights that Hazlitt’s legacy endures. Without his essays, the Romantics would still have triumphed — but their victory would have lacked its sharpest champion, its most eloquent voice in prose.

He remains, for the Romantic Age, what every age of art requires: the critic who understands that art matters because life matters, and who writes as if the truth of beauty were worth defending with one’s whole being.

Closing Reflection — The Foundations of Romanticism

The scroll draws to a pause — not an ending, for the Romantic spirit never truly ends, but a moment of reflection upon what these Senior Romantics have given to the vast and ever-growing river of English literature.

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Dorothy Wordsworth, Southey, Hazlitt — together, they laid down the pillars of a poetic vision that would outlive them all.

They taught us — and continue to teach — that poetry is not a pursuit of artifice but a pursuit of truth; not the province of the educated elite but the common inheritance of all who possess a beating heart and an imaginative eye.

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.”

This was not a slogan — it was a manifesto of the soul. Through Wordsworth’s reverence for Nature and memory, through Coleridge’s fearless journey into the dream and the shadow, through Dorothy’s gentle insistence on the holiness of small things, through Southey’s epic ambition, and through Hazlitt’s unwavering belief in feeling and freedom, the Romantic poets restored to English literature the one thing it had most forgotten: the primacy of the human heart.

When they began their work, poetry was a polished game of wit and form — an art grown too clever to weep, too proud to wonder. When their work was done, poetry had been reclaimed as an instrument of moral vision, emotional healing, and spiritual renewal.

It was a movement born not from institutions but from friendship, conversation, and walks through the countryside — from the shared conviction that the poet’s task is not to impress, but to bear witness to the beauty, sorrow, and mystery of life itself.

Yet even as the Lake Poets shaped this new path, the road ahead was already stirring with other footsteps. Across the English Channel, revolution and repression had birthed a new generation of poets — fiery, passionate, unafraid to blend political radicalism with lyric beauty.

Byron, Shelley, Keats — these names were poised to enter the stage, bringing with them a Romanticism bolder, younger, more tragic in its vision and more lyrical in its song. They would seize the torch lit by Wordsworth and Coleridge and carry it into realms even the Lake Poets had scarcely imagined.

As we fold this first scroll, we do so not with closure, but with an open door. The voices we have heard — sincere, visionary, critical, compassionate — now form the deep foundation upon which the next wave will rise.

And rise it shall. For the spirit of Romanticism is not a fixed form, but a living current — one that flows ever onward, seeking new voices, new visions, new ways of speaking to that deepest part of the human soul that still longs to wonder and to feel.

The red carpet has been unfurled; the first poets have walked its length. Now the path lies open for those who follow.

The Professor folds this first scroll of the Romantic Era with quiet reverence — where words, once chained by form, now walk freely upon the earth. Ahead, the path glows with the promise of younger voices and bolder dreams. The journey of Romanticism continues.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance