Colonial tales, bush ballads, and the art of storytelling when everyone’s sunburnt and slightly suspicious of authority.

By ABS, who believes that the best literature often begins where exile ends—and someone accidentally rhymes “kangaroo” with “screw you.”

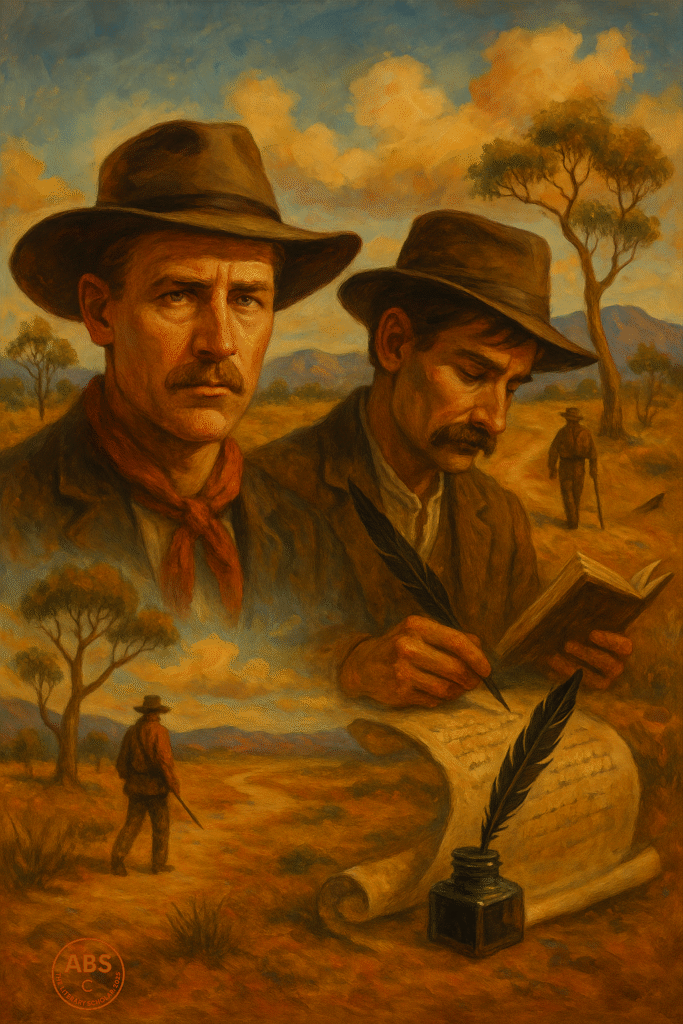

Australian literature didn’t exactly begin with sonnets and salons. It began with chains, silence, and paperwork. Lots of paperwork.

While England was busy producing romantics with swishing sleeves and complicated feelings about flowers, Australia’s first writers were more likely to be shackled, sunburnt, and wondering who approved this life choice. The land was harsh, the accents unrefined, and the ink often mixed with sweat—or something worse.

This was not a continent of metaphors—it was a continent that punched metaphors in the face.

Convicts with Quills: The World’s Least Glamorous Literary Salon

Australia’s earliest English-language writers were, quite literally, criminals. Sentenced to “transportation” (a polite colonial euphemism for exile with scenic beaches and trauma), convicts documented their strange new reality with a tone that ranged from “what the hell is this?” to “you wouldn’t believe what bit me today.”

Many of these convict narratives were diaries, letters, or depositions. Some were published later. James Hardy Vaux, a career criminal with flair, wrote Memoirs of the First Thirty-Two Years of the Life of James Hardy Vaux (1819)—possibly the first Australian autobiography, and certainly the first one written by someone who stole trousers and knew seventeen aliases.

Colonial Echoes: Writing for the Queen (Even If She Forgot Your Name)

For decades, colonial Australia imitated British literature the way a homesick student copies recipes from their mother. The results were familiar but…off.

Writers like Henry Savery (Quintus Servinton, 1830s) tried their hand at novels that sounded like Dickens through a dusty window. Most early works were obsessed with England—either longing for it, escaping it, or blaming it.

But slowly, the land began to creep into the sentences. The tone got grittier. The metaphors stopped asking permission. And the bush started whispering in verse.

Enter the Bush Poets: When Nature Became a Character (and a Critic)

This was the great literary turning point—when Australia wrote the bush, and the bush wrote back.

✦ Banjo Paterson

If you’ve heard of Waltzing Matilda, you’ve met Paterson. His poems celebrated the bushman’s life with rhythm, rhyme, and an eye for underdog glory. The Man from Snowy River turned into national folklore before it became a film, a stage show, and a theme park attraction (probably).

Paterson’s Australia was rugged, loyal, and fond of horses—basically a gentle outlaw with great scenery.

✦ Henry Lawson

If Paterson was the banjo, Lawson was the blues. Gritty, realist, and brooding, Lawson gave voice to hardship, loneliness, and the deep melancholy of the outback. His short stories like The Drover’s Wife and The Bush Undertaker stripped away the romance and left the raw, sunburnt truth.

Together, Paterson and Lawson staged the literary version of a pub brawl in verse—one romantic, one realist, both shaping the soul of Australian identity.

The Federation Years: We Write Because We’re Not England

By the early 1900s, Australia wasn’t just a colony—it was a federation, and the literature started sounding less apologetic and more independently irritable.

Writers like Barbara Baynton (Bush Studies) tore apart the myth of the noble outback and showed it as brutal, sexist, and isolating. Her work was so brutally honest that it made Lawson look like a travel blogger.

This was also the rise of indigenous resistance and forgotten voices—though still suppressed in mainstream publishing, oral traditions and community texts carried deep cultural memory. The written revival would come later, but the roots were unshakable.

Themes That Crawled Out of the Dust

Survival—not metaphorically, but literally

Distance—not just geographical, but emotional

Colonial guilt with a sunburnt twist

Humour as armour, irony as instinct

The land as antagonist, teacher, and occasional murderer

What Defined Early AusLit?

It was literature born of contradiction:

British by origin, but increasingly anti-imperial in tone

Romantic about nature, but wary of its silence

Obsessed with identity, yet allergic to pretension

And above all—it didn’t take itself too seriously. Even when it hurt.

Australian literature began as a survival instinct with syntax. A refusal to disappear. A diary entry shouted into the outback and carried by cockatoos into the future.

ABS folds the scroll, brushes off the red dust, and tips a literary hat to the ghosts of drovers, exiles, and poets with sunstroke.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Who believes that the best epics are written in the margins of history—sometimes in footnotes, sometimes in foot-tracks across the sand.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance