From Mistry to Martel, multiculturalism met narrative—and everything got delightfully complicated.

By ABS, who believes that literary diversity is Canada’s quiet superpower (along with passive-aggressive weather).

If the previous phase of CanLit was all about literary superstars and dystopian disasters, this one is about something quieter but more radical: the changing face of the narrator.

Gone were the days when every story had a pine tree, a Protestant, and a problem with winter. Welcome to the era when Canadian literature burst into cities, languages, cultures, apartments with boiling chai, and taxis full of memory.

Canada was no longer a “melting pot.” It was a brilliantly overstuffed mosaic, and writers who had once been peripheral—or politely ignored—suddenly stepped to the front of the literary line. They brought with them new stories, global histories, and characters who didn’t sound like Robertson Davies with seasonal depression.

This is the scroll where CanLit became, finally, real.

Rohinton Mistry: The Chronicler of Broken Systems and Big Hearts

Born in Bombay, Mistry moved to Toronto and wrote himself into Canadian literary history with prose so tender it hurt.

His masterpiece, A Fine Balance (1995), is technically set in India during the Emergency—but it’s deeply Canadian in its compassion, patience, and unflinching eye for injustice. His other novels, Such a Long Journey and Family Matters, continue this humanist exploration of survival, dignity, and the way bureaucracy kills faster than poison.

Mistry’s characters don’t escape trauma—they live inside it. His work showed Canadian literature that a “foreign” story could still be a Canadian truth.

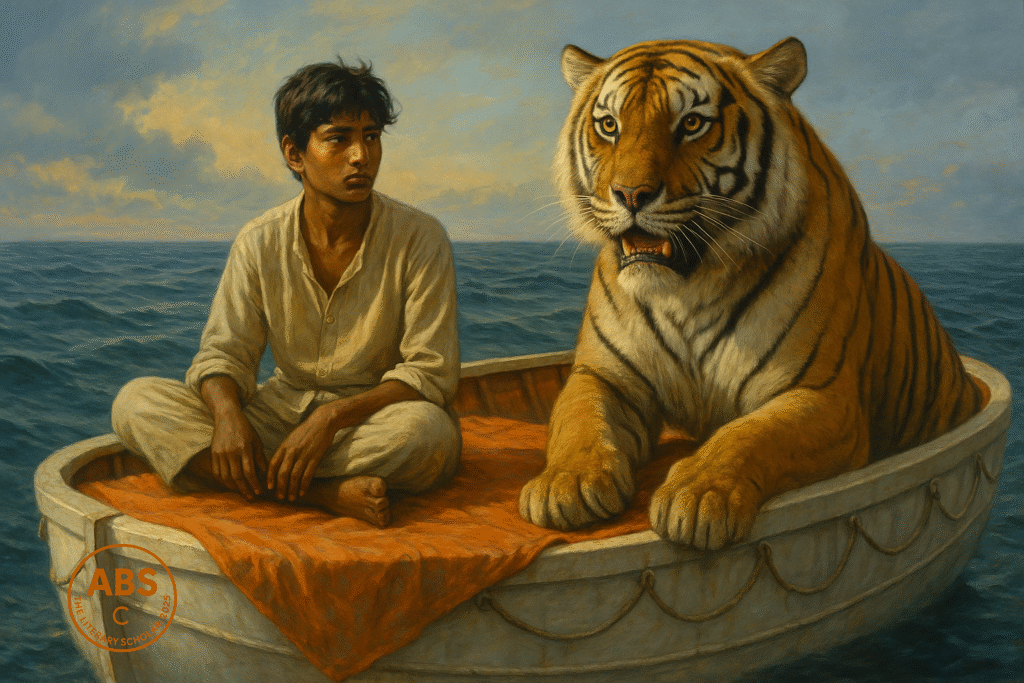

Yann Martel: The Man Who Put a Tiger in a Boat and Got a Booker

Life of Pi (2001) is either:

A philosophical novel about storytelling and survival,

A religious parable with a twist ending, or

A really long metaphor for literary prize bait.

Either way, it worked.

Born in Spain, raised in various countries, and settled in Canada, Martel wrote the kind of genre-bending novel that made CanLit weirdly philosophical—and also popular. It asked Big Questions, made bold narrative moves, and reminded everyone that you could mix magical realism with zoo animals and still be taken seriously.

That’s Canadian progress right there.

Dionne Brand: Poetry, Power, and the Politics of Belonging

If CanLit had an electric current running through it, Dionne Brand would be the source. A poet, novelist, essayist, and activist, Brand doesn’t write about identity—she writes through it, with fire.

Her work—like What We All Long For and A Map to the Door of No Return—deals with immigration, race, gender, queerness, and urban alienation. She writes cities as living things, maps as betrayals, and belonging as an ongoing negotiation.

Her prose is dense, poetic, and unapologetically complicated—because so is the nation it describes.

Other Voices, Loud and Necessary

This era cracked open the CanLit canon and let in the stories it had politely avoided for a century.

Esi Edugyan – Historical fiction with depth and dazzle (Half-Blood Blues, Washington Black)

Kim Thúy – Refugee stories told in prose that breathes like poetry (Ru, Mãn)

Rawi Hage – Lebanese-Canadian grit and urban alienation (De Niro’s Game, Cockroach)

Lawrence Hill – The Black Canadian experience, from The Book of Negroes to The Illegal

Shani Mootoo, Michael Redhill, Souvankham Thammavongsa, David Chariandy—each one broadening the literary lens from immigration to diaspora to identity that refuses one passport.

These weren’t “multicultural writers” shoved into a separate shelf—they were Canadian writers, redefining what Canada even meant on the page.

The Urban Shift: From Forests to Concrete, Finally

Old CanLit loved trees. New CanLit loves apartments, subways, and crowded dinner tables where no one agrees on anything and everyone’s grandma smells different.

Cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal stopped being vague backdrops and became narrative centers—teeming with noise, contradiction, and untranslatable emotion.

Canadian literature finally realized it could be messy, plural, and fluid—and still profound.

Themes That Got Complicated (In a Good Way)

Immigration as transformation—not just for characters, but for the nation itself

Hyphenated identities: the dash that holds everything together and nothing at all

Cities as protagonists, not settings

Languages layered, untranslated, and gloriously resistant to spellcheck

Belonging as a verb, not a guarantee

CanLit’s New Face

This wasn’t just about representation. It was about reconstruction.

The old model—one country, one story—no longer worked. What emerged was a literature of multiplicity: Canadian and Indian. Canadian and Vietnamese. Canadian and queer. Canadian and colonized. Canadian and unsure if “Canadian” even covers it.

And instead of explaining itself to the reader, this CanLit expected the reader to catch up. No glossary. No guide. Just stories—raw, rich, and deeply rooted in real life.

ABS places the scroll on a mosaic-tiled table, beside a half-drunk cup of chai and a subway token. A dozen languages echo softly in the margins.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Who believes that the most powerful lines in literature are the ones no longer written in a single voice—or a single tongue.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance