Instagram Poets, Prize Circuits, and Why Everyone’s Still Misreading African Literature

From ABS, Who Believes literary fame is not always literary understanding.

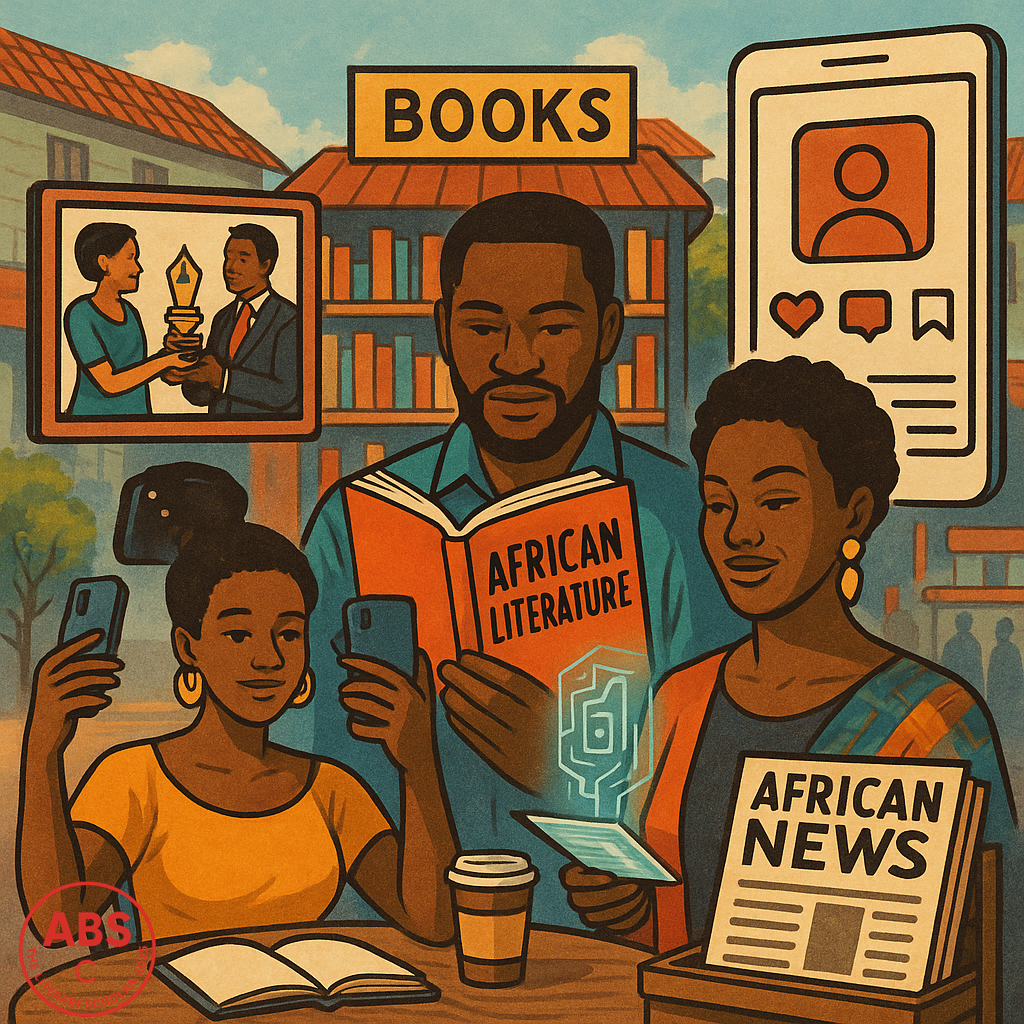

This is where the syllabus ends—and the spectacle begins.

Where the bookshelves gleam with award stickers, and authors smile at literary festivals while secretly wondering if the moderator has read past chapter one.

This is the post-postcolonial stage, where African writers are celebrated, quoted, misinterpreted, translated, exoticized, subtweeted, and sold—often all in one week.

The scroll ends here. But the circus? It’s just getting started.

The Booker Prize Problem: Confetti or Cage?

African writers have become global literary darlings.

The Booker Prize alone has shortlisted or awarded the likes of:

Chigozie Obioma (The Fishermen, An Orchestra of Minorities)

Damon Galgut (The Promise)

Tsitsi Dangarembga (This Mournable Body)

NoViolet Bulawayo (Glory)

All brilliant. All deserving.

But what happens when African writing becomes synonymous with prize-worthy trauma?

Publishers start asking for “voice-driven narratives of suffering.”

Readers start expecting magical poverty, poetic resilience, and a glossary at the back.

And suddenly, writers are no longer storytellers—they’re cultural representatives, trapped in a marketing pitch.

As Binyavanga Wainaina once mockingly wrote in his viral essay How to Write About Africa:

“Always end your book with the dead body of an animal or a person. Preferably both.”

Ouch. Accurate.

The Rise of the Literary Influencer

Not all recognition comes with a golden envelope.

Some African writers today are building platforms outside traditional publishing, using:

Twitter threads

YouTube readings

Spoken-word festivals

Instagram poetry (with or without sunset filters)

Writers like Yrsa Daley-Ward, Lebo Mashile, Upile Chisala, and Nikki May are not just writing—they’re performing, branding, building digital nations of followers hungry for lines that cut and comfort.

But even here, there’s tension:

What’s real? What’s curated?

What’s writing—and what’s content?

In a world where a tweet goes viral faster than a poem gets published, literature is now hashtagged and hyperlinked.

And yet, the stories survive.

Publishing Politics: Who Gets In, Who Gets Framed

Let’s be honest: the global publishing industry still has a “From Africa” section, somewhere between “Travel” and “Postcolonial Guilt.”

And while African writers are breaking in, they’re often expected to explain themselves—or worse, explain Africa.

Enter the gatekeepers: editors, agents, academics, prize committees, panel moderators.

Many are brilliant. Some are well-meaning.

And a few still believe all African novels must involve huts, herbs, or healing.

Writers today navigate:

Translation politics

Copyright theft

Publishing tokenism

Festival panels that ask, “So what’s it like to write in English when you think in Zulu?”

Spoiler: frustrating.

Beyond the Capital Cities: Local Voices, Global Silence

While the world celebrates Adichie and Cole, what about the hundreds of African writers publishing in local languages, regional presses, or online zines with zero funding and a fiercely loyal audience?

Writers like:

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo (Kenya)

Koleka Putuma (South Africa)

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim (Nigeria)

And countless others writing in Kinyarwanda, Amharic, Wolof, Lingala, Shona—without needing a Western stamp of approval

These are the voices building the next canon, one unretweetable masterpiece at a time.

Post-Postcolonial? More Like Post-Everything

Today’s African literature is:

Post-national

Post-trauma (but not post-pain)

Post-genre

Post-publishing gatekeeping

It’s messy, multilingual, and marvelous.

Writers are blending autofiction, essays, fantasy, romance, memoir, and myth.

They’re refusing to explain their cultures in footnotes.

They’re writing for themselves, their readers, their ghosts—and not for The Guardian’s review section.

In this final scroll, we see the liberation of voice.

The ending of expectation.

The joy of the untranslatable.

Literature That Doesn’t Bow

African literature doesn’t need saving, exporting, explaining, or elevating.

It’s already soaring—sometimes with no funding, no spotlight, no translation deal.

This is the final message: African writing is not a genre. It is a galaxy.

And it will continue spinning—beautifully, confusingly, and without asking for permission.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar who believes the final word should never belong to the publisher—only to the page.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance