African Women Writers and the Fine Art of Reclaiming Narrative Without Needing a White Translator’s Approval

From ABS, Who Believes the only thing more powerful than a mother tongue is a mother with a pen.

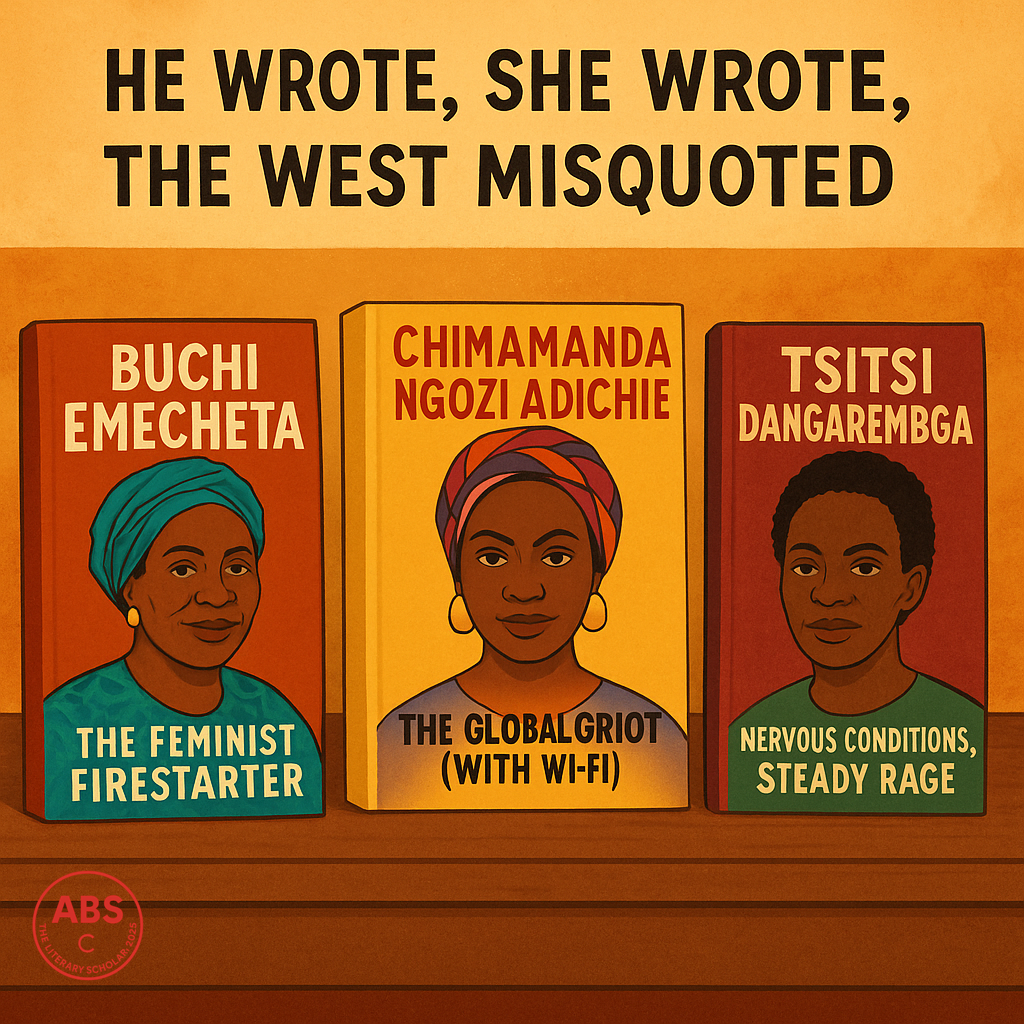

He Wrote, She Wrote, The West Misquoted

African Women Writers and the Fine Art of Reclaiming Narrative Without Needing a White Translator’s Approval

For centuries, African women were spoken for.

By colonial officials. By anthropologists. By husbands. By translators who couldn’t pronounce their names, let alone their truths.

But when African women picked up the pen, the script flipped so hard it left a dent in postcolonial theory.

They didn’t just write back.

They wrote better.

The Feminist Firestarter: Buchi Emecheta

Let’s start with Buchi Emecheta, the Nigerian-born novelist who lit her stories with matchsticks dipped in domestic truth.

Her novels, like Second-Class Citizen and The Joys of Motherhood, read like middle fingers disguised as domestic realism. With calm prose and emotional clarity, Emecheta unpacked the romanticized myth of the sacrificial African mother and replaced it with a raw, blistering reality: poverty, migration, single motherhood, cultural dislocation, and patriarchy wrapped in silence.

And she did it all while raising five children and telling male critics that they could keep their advice and their smug little colonial awards.

Emecheta wasn’t a writer “giving voice” to women.

She was a woman repossessing what was always hers.

Ama Ata Aidoo: When Wit Becomes Weaponry

Then came Ama Ata Aidoo, Ghanaian literary lioness and playwright with the precision of a poet and the punch of a political cartoonist.

Her play The Dilemma of a Ghost (1965) wrestled with cultural hybridity, the West-African returnee narrative, and how even ghosts can’t escape the in-laws. Later, Changes: A Love Story took a scalpel to the myth of romantic fulfillment in a modern African context.

Aidoo’s genius lay in her ability to turn banter into a battle cry. Her characters were educated, messy, funny, flawed, and stubbornly real. And through them, Aidoo questioned everything—from polygamy to capitalism—with the grace of a scholar and the side-eye of a grandmother who’s heard it all before.

Tsitsi Dangarembga: Nervous Conditions, Steady Rage

Tsitsi Dangarembga, the Zimbabwean author of Nervous Conditions, didn’t just write a coming-of-age novel—she wrote a coming-into-consciousness story.

Tambu, the novel’s protagonist, is a young girl who wants an education. Sounds simple, right? But in Dangarembga’s world, even wanting a pencil is a political act. Colonial schooling, gendered silence, family sacrifice, and eating sad maize porridge while watching your brother thrive—it’s all there, narrated with a simmering quiet that says, “I’m angry. I’m just not shouting yet.”

Later, Dangarembga herself became an activist, arrested during peaceful protests. Because some writers write the revolution, and some walk it barefoot.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The Global Griot (With Wi-Fi)

And then, like a literary thunderclap in a TED Talk dress, came Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

From Purple Hibiscus to Half of a Yellow Sun, and her most viral essay We Should All Be Feminists, Adichie became the global face of contemporary African women’s literature—equal parts literary darling and cultural disruptor.

But let’s not get distracted by the Vogue photoshoots. Adichie writes with razor clarity. She takes on:

The Biafran war.

Family trauma.

Faith.

Racism.

Immigration.

And the well-meaning liberal who still asks, “Where did you learn such good English?”

Her short story The Thing Around Your Neck alone should be mandatory reading for every postcolonial guilt-ridden book club.

Adichie didn’t just reclaim the narrative. She mic-dropped it and walked off stage in heels.

Women Without Borders (And Borderlines)

Let’s not pretend these stories are limited to Nigeria or Ghana. Across the continent and beyond:

Leila Aboulela (Sudan): Exploring Islamic identity, exile, and belonging with the subtlety of silk.

Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt): Doctor, firebrand, and walking literary landmine, her Woman at Point Zero still explodes in the reader’s hands.

NoViolet Bulawayo (Zimbabwe): Her We Need New Names made diaspora pain both hilarious and harrowing. Her recent Glory is Orwell with vuvuzelas.

Yvonne Vera (Zimbabwe): Bold. Lyrical. Uncompromising. She made the unspeakable speak.

Sefi Atta, Taiye Selasi, Doreen Baingana, and many others: crafting characters that breathe, bleed, and bake jollof while dismantling patriarchy.

These women weren’t waiting for permission. They were writing in full, unapologetic sentences.

Reclaiming the Tongue—Literally

It’s not just what they said—it’s how.

African women writers used language like a sword dipped in mother tongues. English became elastic, twisted around Igbo, Yoruba, Shona, Arabic, Swahili, and ancestral cadence. Code-switching wasn’t cute—it was defiant.

The West often misunderstood this—calling their work “exotic,” “magical,” or “difficult.”

Translation: “We’re not used to reading about women who do more than suffer beautifully.”

African women wrote complex characters because they lived complex lives—mothers, rebels, daughters, dreamers, economists, refugees, professors, lovers, and not always likable (thank God).

And No, They’re Not a Subgenre

Let’s say this once, slowly:

African women’s writing is not a niche.

It is not “emerging.”

It is not “feminine insight into hardship.”

It is literature. Full stop. And it rewrote the canon while no one was looking.

ABS walks past a library where male authors once lined the shelves like colonial souvenirs.

Now, the air hums with voices that don’t need translation—only recognition.

The pen tilts toward the matriarch, the exile, the girl who read by moonlight. And the West, still dazed, misquotes them at its own peril.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar who believes the most revolutionary ink is often bottled in silence.

And when women write, the world stops pretending it didn’t hear.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance