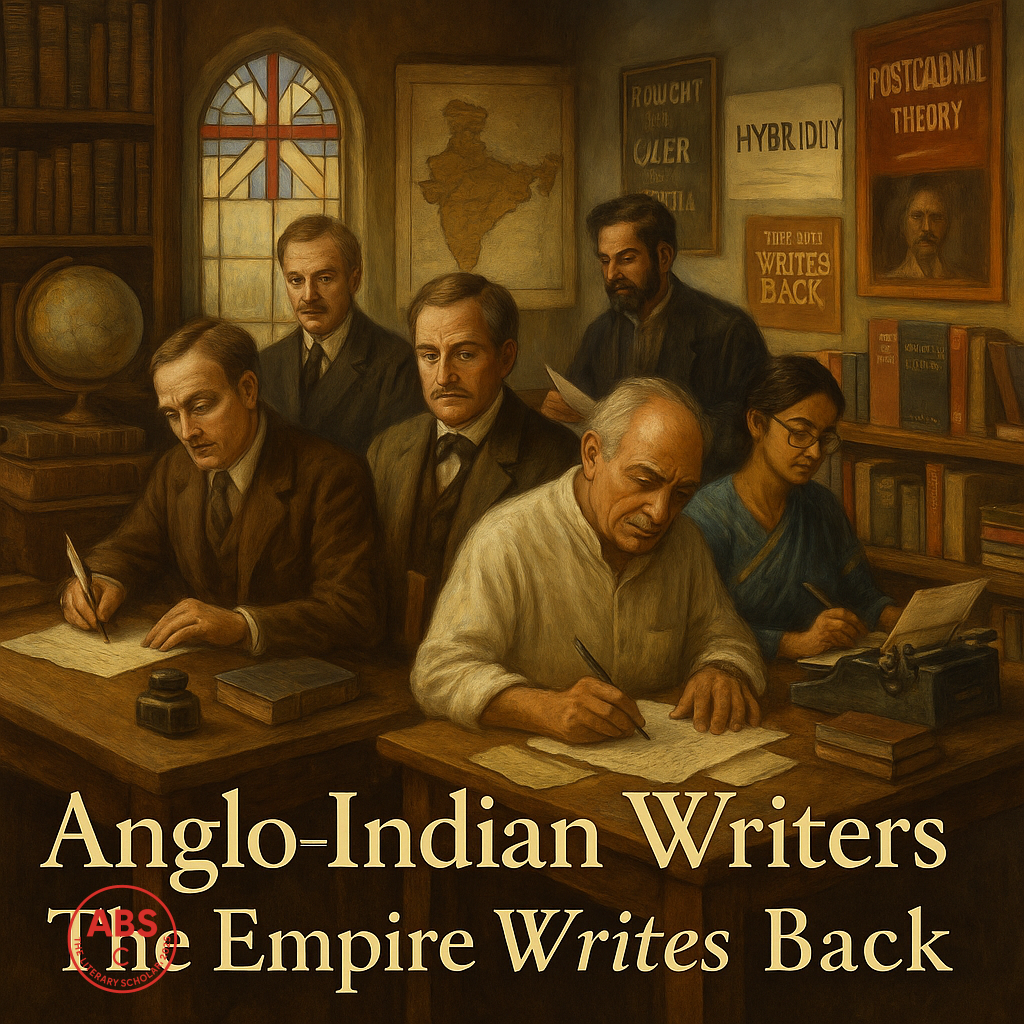

From Kipling’s jungle to Forster’s caves, the British who wrote India—sometimes gloriously, often cluelessly, and always with a baggage allowance

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes the British wrote India like a misunderstood metaphor—and India replied with footnotes.

Let’s begin with the granddaddy of them all: Rudyard Kipling

You knew he was coming. You heard the elephants. You felt the Empire.

Rudyard Kipling is best known for The Jungle Book—a literary zoo of talking animals and colonial allegory where a boy raised by wolves makes more sense than the British Raj.

“East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet.”

—Except when they meet in your novel and it wins you a Nobel.

Kipling loved India—loved ruling it, that is. His prose was lush, confident, and dipped in British superiority. Kim is essentially a love letter to espionage, empire, and pretending to understand Buddhism.

He wrote India like a man who adored the landscape but found the people somewhat inconvenient.

E.M. Forster: The Caves Were Metaphors. So Was the Friendship.

Then there’s E.M. Forster, whose A Passage to India (1924) tried to unravel the mess of colonial relationships—but ended up writing one of the most awkward courtroom dramas in literary history.

“Only connect.”

—Unless you’re Indian, Muslim, or female, in which case, good luck.

Forster’s prose is precise, restrained, and filled with internal sighs. His India is full of misunderstandings, spiritual unease, and very, very long shadows.

He was trying, bless him. He wanted to criticize imperialism—but also hang out with Aziz at the club without upsetting Major Callendar.

Flora Annie Steel: Domestic Goddess of the Raj

Flora Annie Steel is lesser known but highly important. She wrote cookbooks, children’s stories, and The Hosts of the Lord (1900)—a missionary novel so soaked in colonial guilt it practically apologizes in italics.

She saw Indian women, noticed the contradictions of empire, and yet couldn’t quite stop herself from converting the odd fictional orphan.

Steel’s work was somewhere between ethnography and Empire-approved storytelling—sort of the Julia Child of Anglo-Indian anxiety.

John Masters: Action, Adventure, and Unintentional Satire

John Masters, former British officer and writer of Bhowani Junction, gave us historical novels that feel like a Bollywood production directed by Churchill.

His books are military-heavy, emotionally light, and full of characters called things like Rodney Savage. (No, really.)

“India is confusing. Let me simplify it with a love triangle and some marching orders.”

Masters knew India as terrain and troop movement. His work was less about heart, more about heat maps.

Philip Meadows Taylor: The One Who Tried

Before the Victorians could properly condescend, there was Philip Meadows Taylor, whose Confessions of a Thug (1839) introduced the British public to Indian criminal underworlds—and basically invented the concept of “thug” for the West.

He lived in India for years, actually engaged with locals, and wrote with surprising nuance—until, of course, he remembered his audience and tightened the pith helmet.

Still, among the Anglo-Indian pack, Taylor comes off like the exchange student who genuinely tried to learn your language.

Fanny Parkes: She Came, She Journaled, She Judged (and Occasionally Gushed)

Fanny Parkes wasn’t technically a novelist, but her travel memoir Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque is a goldmine of colonial contradictions.

She adored Indian art, food, festivals—and still thought Britain should be in charge of everything.

Her diary is basically: “Today I loved Holi. Also, thank heavens for British order and discipline.”

She’s that tourist who learns your recipes, your prayers, your language, and then asks why your roads aren’t cleaner.

William Dalrymple: The Last (and Best-Dressed) of the Anglo-Indians

Now we jump timelines and land in the present with William Dalrymple, who is technically not a colonial—but is so soaked in Indian history, he’s almost honorary.

“I write history with footnotes. And silk.”

Dalrymple has written White Mughals, The Last Mughal, and The Anarchy—all deeply researched, beautifully told, and occasionally narrated like a Netflix docu-series hosted by a slightly smug uncle with a PhD.

He’s critical of Empire, fluent in Urdu-adjacent pronunciation, and refreshingly willing to admit that Britain kind of messed up.

Dalrymple is the Anglo-Indian writer India actually likes—or at least tolerates at litfests.

What Did They All Have in Common?

They loved India’s color, chaos, and curry.

They mistrusted India’s agency, politics, and potential.

They used English like a colonial passport—with varying degrees of shame and sarcasm.

Some wrote as colonizers, others as confused well-wishers. Some wrote history, others wrote fiction. Many wrote nonsense. But all of them contributed to the mirror India never asked for—but had to look into anyway.

Imagined Scene: The Anglo-Indian Literary Club

Kipling is polishing his Empire medallion.

Forster is looking longingly at Aziz, unsure whether to apologize or analyze.

Flora Steel is rearranging colonial kitchen spices.

Dalrymple is updating his Insta story with a Persian miniature and a Sufi quote.

Fanny Parkes is journaling about everyone’s outfits.

And somewhere in the corner, Taylor whispers, “I tried.”

Final Note from the Scholar

They wrote India in English before India wrote back.

They named its streets, animals, epics, and contradictions—sometimes with affection, sometimes with arrogance.

They made mistakes. Big ones. And a few pages of unexpected brilliance.

And now, they sit in the footnotes of literary history—annotated, interrogated, and occasionally forgiven.

As ABS folds this scroll with a monocle raised and chai slightly over-brewed, one thing is clear:

The Anglo-Indian writer saw India from the veranda.

The Indian English writer walked into the courtyard.

And the rest of us are still rearranging the furniture.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who once read Kipling with admiration, Forster with sympathy, and Fanny Parkes with mild acid reflux

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance