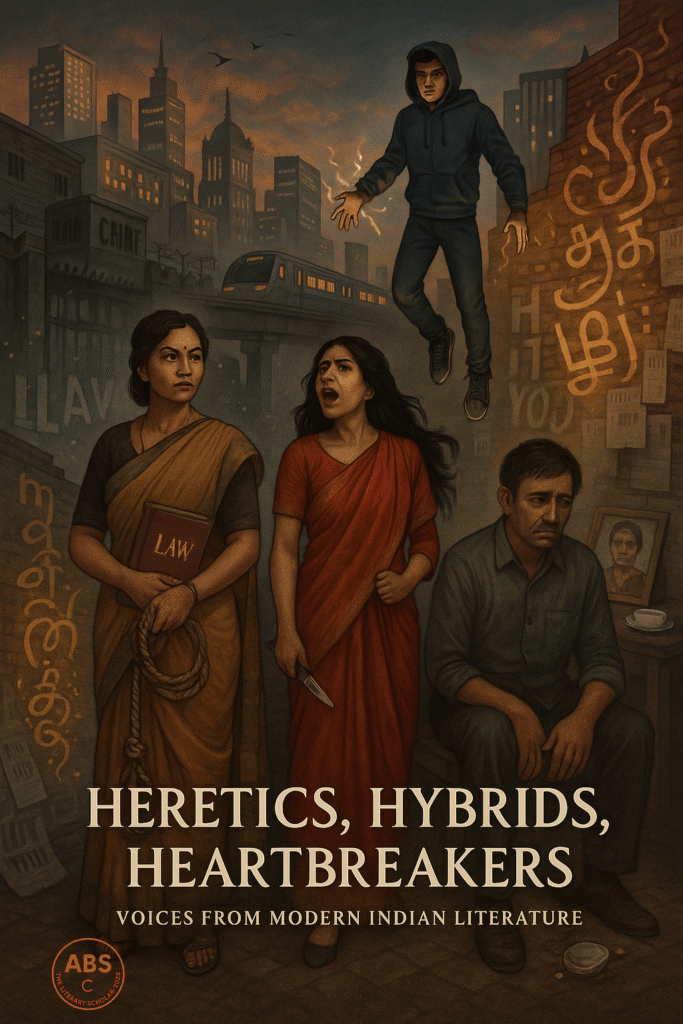

Experimental, regional, poetic, political, and genre-bending voices who carved new shapes into Indian English fiction

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes the best stories are smuggled past genre police wearing metaphor like armour.

Some writers write books. Others write possibilities.

This scroll is not about tradition. It’s about disruption—not always loud, but always deliberate. These are the writers who:

Slipped poetry into prose and politics into breath

Mixed myth with trauma, gender with geography

Wrote from India’s deep interiors and high-rise isolation

Refused to translate themselves—linguistically or emotionally

They did not write to explain India. They wrote to unravel it.

Jeet Thayil: Opium, Poetry, and Postmodern Pain

In Narcopolis (2012), Jeet Thayil gave us Bombay through a smoky haze of drugs, broken saints, transgender courtesans, and poetic ruin.

“Bombay, which obliterates its own history with the air of a man about to sneeze.”

A Booker nominee and an acclaimed poet, Thayil writes like a man possessed—not by style, but by silence. His sentences loop, collapse, regenerate. His characters aren’t citizens—they’re ghosts trying to light cigarettes.

He brought lyrical addiction to Indian fiction—high on language, heavy on grief.

Jerry Pinto: When Mothers Break and Sons Remember

Em and the Big Hoom (2012) is one of those novels that should come with a warning: May cause internal crumbling.

Jerry Pinto tells the story of a family dealing with a bipolar mother—Em—through the eyes of her loving, bewildered son.

“She laughed like a person who has been allowed to weep after many years of holding it in.”

It’s tender, unsparing, funny, and devastating. Pinto’s prose is clean and devastatingly honest. He shows that you don’t need plot twists when reality is already unbearable.

He gave Indian fiction a mental health memoir without melodrama—and with unimaginable heart.

Meena Kandasamy: Poetry with a Switchblade

Reading Meena Kandasamy is like holding a live wire—electric, unapologetic, necessary.

Her novel When I Hit You (2017) is a fictionalised account of marital abuse, told with poetic rage. Her poetry—Ms Militancy, Exquisite Cadavers—is Dalit, feminist, lyrical, and incendiary.

“He called it marital sex. I called it marital rape. He called me a liar. I called myself a writer.”

She doesn’t write to entertain. She writes to exorcise. And you will feel every syllable.

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar: The Adivasi Will Not Be Edited

With The Adivasi Will Not Dance (2015), Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar brought the Santhal experience into mainstream consciousness—and controversy.

He writes about tribal identity, sexuality, poverty, and dignity without filters. His stories were banned. Then celebrated. Then studied.

“I have danced for your development. Now let me sit in silence.”

He doesn’t seek your sympathy. He demands your discomfort.

Samit Basu: Superheroes in South Delhi

What if Indian fiction had capes, conspiracies, and satire?

Samit Basu’s Turbulence (2010) gave us a world where Indian superheroes emerge on a London-to-Delhi flight. And yes, they argue about power, politics, and who gets the best hashtags.

“With great power comes a need for serious brand management.”

Basu blends sci-fi, social commentary, and subcontinental sarcasm. He made genre fiction desi—and proud of it.

K.R. Meera: The Hangwoman of Malayalam Guilt

Translated into English, K.R. Meera’s Hangwoman is part psychological thriller, part feminist myth.

Chetna, the protagonist, is the first female hangwoman in a family of executioners. But the book is not about death—it’s about inheritance, violence, and the slow strangulation of being a woman in a man’s job.

“No noose can tighten as silently as expectation.”

Meera’s prose—translated with aching brilliance—feels like thunder after silence.

Annie Zaidi: Prose in Protest, Essays in Elegy

Annie Zaidi has done it all—novels, essays, short stories, journalism, stage plays. Her Prelude to a Riot (2020) is a slender, searing book about rising communal tension—told not through narrative, but through interior monologues.

“Hate is not a storm. It’s the slow fog that settles in.”

Zaidi writes about the unspeakable, with restraint that cuts deeper than rage.

Temsula Ao: Echoes from the Hills

From Nagaland, Temsula Ao brought us These Hills Called Home—a haunting short story collection about insurgency, loss, and survival in the Northeast.

“We live in a place where history is written in whispers and disappearances.”

Her writing is poetic, tragic, and unflinching. She gave Indian English literature geographies it had forgotten, and memories it would rather avoid.

Perumal Murugan: The Man Who Died, and Then Wrote Again

One Part Woman was a novel about love, infertility, and societal pressure. When it was published, Perumal Murugan was hounded by protests. He declared: “Writer Perumal Murugan is dead.”

Then he returned—with Poonachi, a novel about a black goat in a totalitarian state.

“A goat can endure everything. Even silence.”

Murugan writes in Tamil. But his words in translation pierce English literature like grief through cloth. He is a resurrected heretic, and we need more of him.

Tanuj Solanki: The Corporate Dissenter

In The Machine is Learning (2020), Tanuj Solanki gave us the first Indian English novel that feels like a resignation letter drafted inside a CRM dashboard.

“In our world, there are no dreams—only deliverables.”

His prose is stripped, soulless by design, and eerily human. He writes of the working Indian millennial with existential clarity and IT-level despair.

Priya Sarukkai Chabria: The Poet Oracle of Hybrid Forms

Novelist, translator, poet, thinker—Priya Sarukkai Chabria does not obey genre.

From Clutch of Indian Masterpieces to her retelling of Andal’s verses, her work is sensual, sacred, experimental, and exquisitely disobedient.

“Translation is resurrection. But also haunting.”

She reimagines myths, genders, voices—and turns every sentence into an act of meditation.

Ranjit Hoskote: The Philosopher-Poet of Displacement

His poetry reads like metaphysical footnotes to forgotten civilizations. Ranjit Hoskote writes with global urgency and ancient patience.

“The sky is a scroll written in missing ink.”

If India had a mystic laureate who drank espresso and studied architecture, it would be Hoskote.

Imagined Scene: The Quiet Riot

Thayil reads a poem in slow motion.

Pinto wipes his glasses, then your heart.

Meena Kandasamy corrects the moderator’s question with fire.

Murugan smiles quietly, writing about goats again.

Temsula Ao hums a lost song.

Annie Zaidi takes notes no one sees.

Samit Basu wonders if AI is listening.

Hoskote translates the whole evening into air.

What They Gave Us

They gave us language unhooked from tradition.

They gave us India without explanation.

They gave us literature as risk.

And often, literature as resistance.

They didn’t ask permission. They wrote. They bled. They published. They shook the form.

And now, Indian English literature will never be able to “go back.”

As ABS folds this scroll—eyes slightly wet from Em’s laughter, pulse still caught in Kandasamy’s flame, mind reeling from Hoskote’s inkless scroll—one thing is certain: sometimes, it’s the writers on the edges who redraw the whole map.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who knows that silence isn’t absence—and that the heretics always write the most necessary scrolls

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance