From Karnad to Amish, from Dattani to Sanghi—these writers made Indian English loud, layered, and wildly popular

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes that popularity isn’t a sin—and plot twists deserve literary respect too.

Not all literature wants to be quoted in dusty journals. Some of it wants to be staged, sung, screen-adapted, or snatched from railway station bookstalls before the train leaves Platform 4.

This scroll is for those who wrote with rhythm, risk, and reach—the ones who made Indian English feel performative, addictive, adaptable. They didn’t all seek critical approval. But they found readers. Millions of them.

These are the dramatists, mythmakers, mass-market moguls, and cultural sages who proved that you don’t have to write “like Salman Rushdie” to matter. Sometimes, you just need a mic, a myth, or a masala twist.

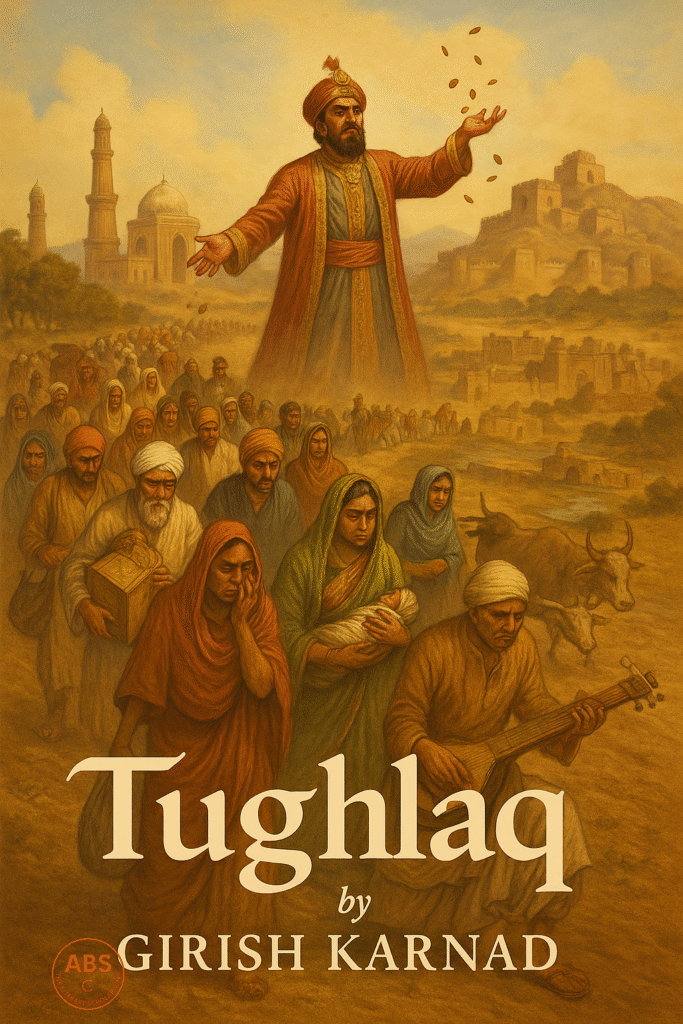

Girish Karnad: Myth, Madness, and Modern India on Stage

Girish Karnad didn’t just write plays—he resurrected India’s past, slapped it with modern anxiety, and staged it under theatrical lighting.

Tughlaq (1964) gave us a Delhi Sultan who spoke like Hamlet and ruled like a tragic bureaucrat. Hayavadana (1971) brought folk tales, identity swaps, and head transplants to the urban stage.

“When you have two heads and one heart, confusion is inevitable.”

Karnad blended Sanskrit drama, European absurdism, and postcolonial irony. He made audiences think, fidget, and occasionally gasp. His theatre wasn’t polite—it was pointed. Political. Mythical. Profound.

He brought gravitas to Indian English drama—and never needed a single spotlight to do it.

Mahesh Dattani: The Urban Confessor of Our Stage

While Karnad used myth, Mahesh Dattani used mirrors—to reflect everything Indians preferred not to see.

His plays—Final Solutions, Dance Like a Man, Bravely Fought the Queen—dealt with communal tension, gender identity, closeted lives, and cultural hypocrisy.

“We all wear masks, and the longer we wear them, the harder it is to take them off.”

Dattani was the first Indian playwright in English to win a Sahitya Akademi Award. And rightly so. He made the Indian English stage urban, anxious, modern, and queer—long before Netflix caught up.

His plays weren’t performances. They were confessions.

Arun Kolatkar: The Poet Who Went to Jejuri and Found God in Dust

Arun Kolatkar’s Jejuri (1976) is a series of poems about a trip to a rural temple town. That’s it. And yet, it’s considered one of the most iconic works in Indian English poetry.

“The bus goes rattling over the stone / and then stops. / The temples are there on the hill.”

Simple? Yes. But also sly, subversive, surreal.

Kolatkar wrote like a man unimpressed by sanctity—but deeply in love with language. His verse is minimalist, visual, often hilarious. He saw India with one eye on the divine and the other on the absurd.

He didn’t raise his voice—but you heard him anyway.

Vikas Swarup: The Quizmaster of Fiction

Before it became Slumdog Millionaire, it was Vikas Swarup’s Q&A (2005)—a clever, cinematic novel where every quiz question unlocks a chapter of a life lived in hardship, hope, and Bombay madness.

“Every man has his destiny. Fate writes the script, and we act it out.”

Swarup, a diplomat by day, turned out to be a storyteller by night—one who blended social realism with Bollywood beats and global appeal.

He made fiction look effortless, readable, and infectiously plot-driven. His success proved that Indian English literature could still tell stories without literary gymnastics—and win over the world.

Anurag Mathur: The OG of Desi Abroad Confusion

In The Inscrutable Americans (1991), Anurag Mathur gave us Gopal, a small-town Indian boy trying to survive the U.S. while navigating race, culture shock, and nudity.

“I am thinking of becoming a liberated man. I have started removing my shirt in front of women.”

The novel is laugh-out-loud funny, painfully awkward, and still hits home for every Indian who’s ever overpacked food for a foreign trip.

Mathur’s novel became a cult campus classic—because behind the satire was a real sadness, a cultural estrangement that refused to fade with passport stamps.

Amish Tripathi: The Mythmaker Who Made Sati a Warrior and Shiva a Hunk

If the gods had PR agents, Amish Tripathi would be their brand manager.

His Shiva Trilogy (starting with The Immortals of Meluha, 2010) turned Lord Shiva into a Tibetan tribal chief with killer abs and a moral dilemma. And readers ate it up—turning him into a one-man publishing juggernaut.

“A man becomes God not because he creates the world. But because he chooses to fight for it.”

Amish took ancient stories and gave them cinematic pacing, political undertones, feminist updates, and clean prose. His books read like blockbuster scripts—and that’s part of the genius.

He didn’t write to win awards. He wrote to win readers. And in doing so, he redefined mass-market Indian mytho-fiction.

Ashwin Sanghi: The Conspirator Who Out-Danned Dan Brown

If Amish is the poet-priest of Indian myth, Ashwin Sanghi is the conspiracy theorist at the temple gates.

His Chanakya’s Chant, The Krishna Key, and The Rozabal Line blend politics, myth, crime, and theology into unputdownable thrillers.

“The lines between history and myth blur when belief becomes currency.”

Sanghi’s research is deep, his plots tangled, and his faith in the reader’s curiosity—absolute.

He made myth cool for the politically skeptical, the thriller-hungry, and the spiritually intrigued.

Chetan Bhagat: The Man You Love to Hate (and Secretly Read)

Say what you want, but Chetan Bhagat changed the game.

Five Point Someone (2004) wasn’t just a campus novel—it was a cultural eruption. Suddenly, engineering students were protagonists. English was Indian in accent and pace. Love stories were about bunking class and failing exams.

“The world is full of Chetans. Some get lucky. Some don’t.”

And he was lucky—but also smart. His books (2 States, One Night @ the Call Center, The Girl in Room 105) weren’t masterpieces, but they were relatable, fast, and oddly confessional.

Bhagat democratised English fiction in India. For some, that was a tragedy. For others, a lifeline.

Critics frowned. Readers lined up. And cinema cashed in.

Sudha Murty: The Moral Storyteller We Secretly Needed

In an age of irony, Sudha Murty wrote with gentle clarity and grandmotherly warmth.

Her stories—Wise and Otherwise, The Day I Stopped Drinking Milk—aren’t edgy, but they are honest. She writes about kindness, struggle, integrity, and everyday heroes.

“A great man is different from an eminent one in that he is ready to be the servant of the society.”

She didn’t try to impress the literati. She tried to reach children, parents, classrooms, villages—and succeeded. Her prose is clean. Her impact, quiet. Her reach, massive.

She reminded us that storytelling is also about service.

Irawati Karve: The Anthropologist Who Dissected Epics

In Yuganta (1967), Irawati Karve rewrote the Mahabharata—not as a devotional saga, but as human drama.

“The Mahabharata does not let us be satisfied with easy judgments.”

Karve, a sociologist and anthropologist, stripped mythology of its moral polish and showed us its psychological, emotional, and political dimensions.

She was ahead of her time—bridging literature, culture, history, and gender. If you haven’t read her, you haven’t fully read the Mahabharata.

Imagined Scene: Bestseller Roundtable at the Lit Fest

Karnad quotes Kalidasa, unimpressed by Bhagat’s jacket cover.

Dattani nods politely while editing someone’s script in his head.

Swarup suggests turning the conversation into a screenplay.

Ashwin Sanghi starts a theory linking all their protagonists to the Rig Veda.

Sudha Murty brings laddoos.

Chetan Bhagat live-posts the whole thing.

What They Gave Us

They gave us reach. Performance. Plot. Popularity.

They were laughed at, loved, pirated, translated, and sometimes banned.

They were not always canonical. But they were unavoidable.

They proved that Indian English literature didn’t have to be elite to be literary. And sometimes, mass appeal is the most radical act.

As ABS closes the scroll—smiling at the thought of Shiva as an action hero, recalling Jejuri’s sacred dust, and secretly forgiving Bhagat for everything before 2010—there’s a quiet respect. These writers broke in through side doors. And then made the house feel larger.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who occasionally reads bestsellers on flights and refuses to apologise for it

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance