Khushwant Singh, Nissim Ezekiel, Shashi Deshpande, Shashi Tharoor, and other bold voices who shaped Indian English literature from within

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes literary rebellion requires ink, irony, and absolutely no permission slips.

By the time the world had made peace with the fact that Indians could write Booker-winning epics and diaspora heartbreaks, a quieter rebellion had already taken place. One not wrapped in silk metaphors or award-stage spotlights, but in crisp satire, stubborn feminism, bitter verse, sexual honesty, and literary side-eyes at sacred cows.

This scroll is not about a movement—it’s about mavericks. The rule-benders. The line-blurrers. The ones who weren’t trying to represent India—they were just trying to write, and refused to edit out the mess.

Here are the voices who didn’t fit into literary templates. They shredded them.

Khushwant Singh: The Dirty Old Man Who Gave Us Partition’s Clearest Scream

If literature were a wedding, Khushwant Singh would be the uncle who brings whiskey to the prayer room and still gives the best historical analysis at the dinner table.

His classic Train to Pakistan (1956) is arguably the most chilling, emotionally restrained account of Partition ever written. No sentimentalism. No patriotic fluff. Just raw, agonising humanity.

“Freedom is for the educated. The rest of us will have to suffer.”

And suffer they do—across borders, trains, bodies.

But Singh wasn’t just a chronicler of blood-soaked history. He was also the man behind The Company of Women and Truth, Love & a Little Malice—books so dripping with sex, irreverence, and political sarcasm, they made prudes tremble and liberals grin.

He mocked everyone. Including himself. And that’s why he remains unforgettable.

Nissim Ezekiel: The Poet Who Found God in Bombay Taxis

Move over, romantic hills and lotus ponds. Nissim Ezekiel gave Indian English poetry a permanent Bombay address—and filled it with ordinary people, absurd rituals, and gentle existential panic.

“I am not a Hindu, and my background makes me a natural outsider…”

That was Ezekiel: deeply Indian, profoundly skeptical, and perpetually urban.

He wrote poems titled The Railway Clerk, Goodbye Party for Miss Pushpa T.S., and The Professor—turning pedestrian English into poetic gold. His tone was dry, ironic, and secretly affectionate.

He questioned everything—religion, identity, nationalism, even punctuation. And in doing so, he became the godfather of Indian English poetry.

Without him, there’d be no Jeet Thayil, no Dom Moraes revival, no witty poetry readings where people pretend to understand enjambment.

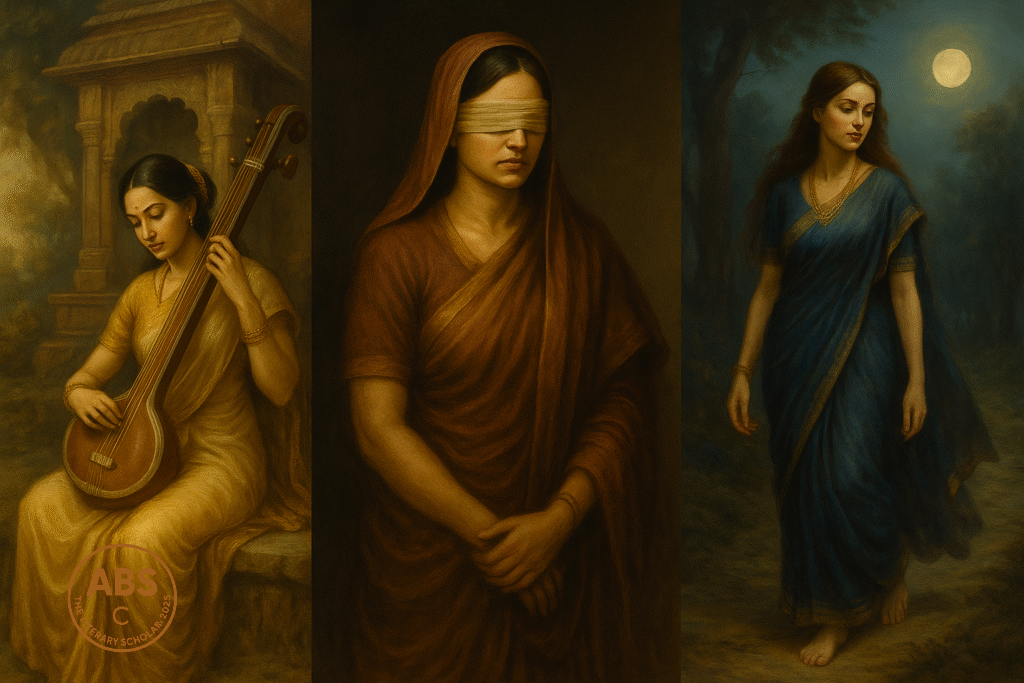

Shashi Deshpande: Silence, Suffering, and the Softest Kind of Rebellion

While the men were shouting about Partition and politics, Shashi Deshpande quietly opened a notebook and began to write the interior lives of Indian women—with so much restraint, it thundered.

Her That Long Silence (1989) is a masterpiece of stillness. Jaya, the protagonist, doesn’t scream. She reflects. She absorbs. And eventually, she decides: enough.

“A woman can never be herself in the world of men.”

Deshpande’s fiction isn’t angry—but it’s tired. Tired of expectations, hypocrisy, and the suffocating architecture of marriage, motherhood, and muted dreams.

She writes not of heroines, but of survivors. Her prose is crisp, clean, and devastatingly close to home.

If Virginia Woolf had been born in Karnataka and handed a pressure cooker, she would’ve written like Shashi Deshpande.

Shashi Tharoor: Myth, Satire, and a Dictionary Per Chapter

Imagine Mahabharata re-told through political satire, laced with puns, allusions, and footnotes. Then imagine it edited by a man who writes faster than most people read.

Welcome to Shashi Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel (1989)—where Bhishma becomes a British bureaucrat and Draupadi becomes democracy itself.

“India is not a nation, but a notion.”

Tharoor’s fiction is clever, erudite, verbose, and drenched in irony. From Riot to Show Business, he dismantles power, nationalism, media, and myth—all while using words that send readers scrambling for a thesaurus.

Yes, he’s a parliamentarian. But in his fiction, he’s a myth-smuggler with a PhD and a wicked smile.

He doesn’t write to soothe. He writes to show off. And somehow, we’re better for it.

Manju Kapur: Domesticity as Dissent

Manju Kapur could write an entire revolution inside a living room. In Difficult Daughters (1998), she gave us a woman who dares to love, read, and think—during the Partition.

“It was not my fault. I did not want to be good.”

From Home to Custody, Kapur’s novels explore the quiet suffering and subversion of Indian women trapped in homes with too many walls and too little voice.

Her prose doesn’t shout. But it peels. She shows how control isn’t always violent—sometimes, it’s just cultural.

And in the world of post-liberalised Indian fiction, she brought back the inner world of middle-class women as a battlefield.

Amit Chaudhuri: The Man Who Made Melancholy an Art Form

If action bores you and metaphors delight you, welcome to Amit Chaudhuri’s world. In A Strange and Sublime Address, he wrote an entire novel about nothing—and made it profound.

“The hum of the fridge was the only sound of continuity.”

Chaudhuri writes like Proust went to Calcutta. His prose is minimalist, lyrical, and obsessed with the ordinary: smells, afternoons, old houses, family routines.

He doesn’t need drama. He needs monsoon light falling on cracked walls.

Some find him boring. Others worship him. But no one can deny that he made Indian fiction listen to itself again.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: The Outsider Who Knew Too Much

A German Jew who moved to India, married a Parsi architect, and wrote Heat and Dust (1975)—a novel that dissects colonialism with the detachment of someone who’s seen too many dinner parties go wrong.

“India always changes people, and I have been no exception.”

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala captured India through the eyes of the half-included: women, foreigners, wanderers, lovers.

She won the Booker. She wrote Oscar-winning screenplays. And she chronicled the tension between the West’s obsession with India and India’s obliviousness to the West.

Sharp, ironic, elegant—and always a little suspicious of sincerity.

Namita Gokhale: Publishing, Parody, and Postmodern Play

Her debut Paro: Dreams of Passion (1984) was so outrageous, readers didn’t know whether to burn it or laugh.

“Paro believed that virtue was just another form of oppression.”

Namita Gokhale is bold, experimental, and happily irreverent. She pokes fun at Delhi elites, gender clichés, and literary pretensions.

As co-founder of the Jaipur Literature Festival, she has also built platforms for others—while writing books that blend satire, sensuality, and spiritual wanderings.

She reminds us that literature doesn’t have to be solemn. It just has to be sharp.

Geeta Hariharan: Myth, Woman, Fire

The Thousand Faces of Night (1992) is part novel, part myth, part feminist fury dressed in graceful sentences.

Geeta Hariharan uses Indian mythology not as ornament, but as resistance. Her women are not victims—they are watchers, mourners, rebels.

“To name the pain is to begin to own it.”

She’s not writing for the mainstream. She’s writing for memory, myth, and the kind of woman literature forgets.

Pankaj Mishra: Intellectual Discontent in Stylish Sentences

Whether writing Butter Chicken in Ludhiana or The Romantics, Pankaj Mishra is always two steps ahead of the discourse—and mildly irritated.

He doesn’t do happy endings. He does critiques of globalisation, cultural anxiety, and youthful despair.

Think of him as the literary cousin who got out of small-town India and now writes blistering op-eds in The Guardian while attending panels in Berlin.

Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi: Sensuality, Sorrow, and Style

His debut The Last Song of Dusk (2004) is lush, magical, tragic, and soaked in moonlight and misfortune.

“Some people are born to break your heart.”

Shanghvi writes like a dream gone wrong—beautiful, stylised, painful. His prose is florid, unapologetic, and intoxicating.

He brought queer desire, sensuality, and gothic beauty into Indian fiction—and left everyone emotionally stunned.

Shobhaa De: High Heels, Low Blows, and Bold Prose

Mock her at your peril. Shobhaa De gave Indian fiction its first unapologetically urban, unapologetically female, unapologetically bold voice.

From Starry Nights to Selective Memory, she chronicled Mumbai’s underbelly of desire, glamour, hypocrisy, and media madness.

“Morality is a public performance. What you do at home is your business.”

She writes like she speaks—fast, fierce, and headline-ready. Literary snobs hated her. The public loved her. And honestly, the canon owes her a drink.

Rama Mehta: The Quiet Matriarch

Inside the Haveli (1977) is a novel that feels like history whispered through curtain folds.

Rama Mehta captured the tension between tradition and modernity from inside a Rajasthani household—without judgement, but with layered insight.

She was writing about domestic power long before it became fashionable.

Imagined Scene: The Literary Club with No Rules

Khushwant Singh spikes the tea. Shashi Deshpande sighs but stays. Shashi Tharoor quotes Sanskrit to the waiter. Ezekiel scribbles a haiku about mosquitoes. Manju Kapur adjusts her shawl and rewrites the guest list. Shanghvi makes it romantic. Shobhaa De live-tweets it. The rest argue about plot while Ruth Prawer Jhabvala quietly wins another award.

What They Gave Us

They gave us literature that:

Didn’t beg for approval

Didn’t follow movements

Didn’t apologise for mess

And didn’t care whether they were canonised

They wrote politics through satire, feminism through footnotes, and heartbreak through humour. They were Indian, English, literary, scandalous, philosophical, funny, serious, stylish—and real.

As ABS closes this scroll—smiling at Deshpande’s restraint, wincing at Singh’s boldness, and secretly quoting Ezekiel under breath—there’s satisfaction. These were the writers who weren’t chasing prizes. They were chasing truth. And sometimes, just a good story.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who never flinched at honest fiction—even if it came wrapped in scandal, scorn, or sequins

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance