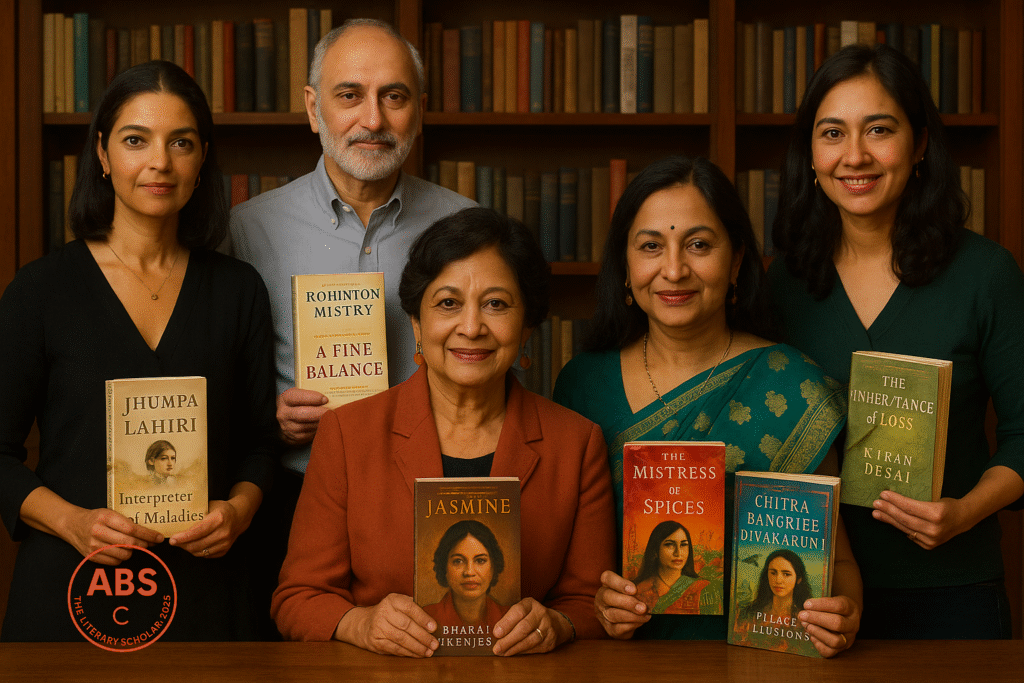

Jhumpa Lahiri, Rohinton Mistry, Bharati Mukherjee, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni & diaspora writers who carried India in their suitcases

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes exile writes the best literature—and nostalgia is just homesickness in a prettier font.

They left India, but India never really left them. It clung to their characters like turmeric in Tupperware. It haunted their prose, whispered through their metaphors, and occasionally showed up uninvited at dinner parties with old myths and new memories.

Welcome to the diaspora—where English isn’t just a language, but a cultural checkpoint; where identity is declared at customs, and stories are the emotional baggage no one weighs but everyone feels.

This scroll celebrates the writers who didn’t just cross continents. They crossed selves—and came back bearing fiction that echoes in two languages, three generations, and one too many awkward parent-child conversations.

Jhumpa Lahiri: The Queen of Quiet Catastrophes

No one has made immigrant sadness so elegantly fashionable as Jhumpa Lahiri.

With her Pulitzer-winning debut Interpreter of Maladies (1999), Lahiri introduced us to an entire sub-genre: Elegant Misery in Massachusetts. Her characters don’t explode; they sigh. They don’t rebel; they remove their shoes carefully before entering existential crisis.

“Still, there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have traveled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known…”

Yes, Jhumpa. And we are all now unsure of what to do with our emotions.

In The Namesake (2003), she gave us Gogol Ganguli, a boy burdened by a Russian name, Bengali parents, and the sinking realization that no matter what he chooses—he will never be entirely at home.

Lahiri writes with surgical precision and poetic detachment. She’s the literary equivalent of sipping cold tea while staring at old photographs. Her power lies in restraint—in the heartbreak that never quite announces itself, but sits quietly at the kitchen table while your identity falls apart.

She’s also the only person who won a Pulitzer for quietly observing loneliness over daal.

Rohinton Mistry: Epic Sorrow, Perfectly Typeset

If Lahiri is the sigh, Rohinton Mistry is the storm. His novels are not just books—they are brick-sized tragedies soaked in Parsi wit and human compassion.

A Fine Balance (1995) is not for the faint of heart. Set during the Emergency, it’s the story of four characters trying to survive caste, cruelty, corruption, and bad tailoring—all while clinging to some shred of hope.

“You have to maintain a fine balance between hope and despair.”

Spoiler: despair usually wins. But oh, what beautiful despair.

Mistry’s writing is lush, slow, deliberate. He builds entire political histories into cups of tea. He turns slums into epics. He doesn’t tell you things are unjust—he makes you live through it, one page, one heartbreak, one bureaucratic horror at a time.

In Such a Long Journey (1991), he follows Gustad Noble, a man watching his family, country, and plumbing fall apart. It’s satire dressed in sadness, and vice versa.

Mistry’s brilliance? Making large-scale political critique feel like an intimate whisper from someone who’s just lost their last soap coupon.

Bharati Mukherjee: From Jasmine Fields to Identity Firestorms

Before Jhumpa ever packed her metaphors, Bharati Mukherjee was already busy blowing up the idea of the “model immigrant.”

Jasmine (1989) is not just about immigration. It’s about reinvention by fire. Its protagonist goes from a village girl in India to an illegal immigrant in America to a woman who keeps morphing with each trauma and encounter—like a one-woman diaspora myth.

“There are no harmless, compassionate ways to remake oneself.”

Mukherjee’s characters don’t fit in. They don’t even try. They survive, adapt, betray, seduce, shoot, flee, and rebuild. This is not the sepia-toned nostalgia of the homeland. This is the messy, bloody business of forging identity in a foreign land—and sometimes losing your old one entirely.

She was one of the first Indian-American writers to declare: “We are here, and we don’t owe you politeness.”

Where others whispered between cultures, Mukherjee kicked the door down.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni: Magic, Migration, and Matriarchy

Now bring in Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, who decided that if immigrants must suffer, they may as well do it with spices, stories, and a little enchantment.

In The Mistress of Spices (1997), we meet Tilo, a mysterious spice-shop owner who heals the diaspora’s spiritual wounds with cardamom, turmeric, and occasionally stern life advice.

“Spices are a form of magic, but their magic is nothing if not earned.”

Divakaruni blends magical realism with feminist storytelling, diaspora anguish with ancient epics. In Arranged Marriage, she crafts short stories that explore women trapped between choice and tradition, love and obligation, home and Home (with capital H and collective guilt).

And then there’s The Palace of Illusions (2008), where she takes the Mahabharata and retells it from Draupadi’s perspective—because if anyone had a story to tell, it was the woman married to five men and still managing palace politics.

Divakaruni reminds us that immigration is not just a political act—it’s a mythic journey. And sometimes, even the visa gets cursed.

Kiran Desai: Of Inheritance, Loss, and Freezing in the Himalayas

And now, the sharp, Booker-winning voice of Kiran Desai. Her The Inheritance of Loss (2006) is what happens when colonial hangovers, economic migration, and postmodern malaise all rent a room in the same falling-apart mansion.

Set between Kalimpong and New York, the novel follows a retired judge, his orphaned granddaughter, and his cook’s son illegally working in America. It’s beautiful. It’s brutal. It’s occasionally bilingual. And it doesn’t come with a map.

“Could fulfillment ever be felt as deeply as loss?”

Apparently not. Desai’s prose is lush, lyrical, and devastating. She captures the intergenerational ache of postcolonial identities—people still looking for approval from empires long gone, and struggling to belong in countries that never really asked them to.

Her characters don’t seek resolution. They seek survival—emotional, linguistic, geographical.

Desai proves that immigration isn’t just a plotline. It’s a wound that writes itself, often without consent.

Imagined Scene: Diaspora Book Club (Bring Your Own Cultural Confusion)

Let’s imagine this unlikely literary gathering:

Lahiri brings snacks no one touches because they feel guilty eating in front of her prose.

Mistry sits quietly, composing a 700-page eulogy for a side character.

Mukherjee walks in, changes her name, and rewrites everyone’s backstory.

Divakaruni burns incense and casually mentions that Draupadi was misquoted for centuries.

Desai forgets the agenda and writes a metaphor about colonial leftovers and refrigerator frost.

They argue over memory. They bond over rootlessness. And they never agree on which homeland to miss.

What They Gave Us

They gave us diaspora not as location, but as condition. These writers showed us that India is not a country—it’s a frequency. Sometimes it crackles. Sometimes it sings. But it never quite goes silent.

They wrote about:

Homesickness with no cure

Cultural contradictions that cancel each other out

Mothers who cling, daughters who flee, and men who miss trains and meaning at the same time

Mythology served with microwaved dinners

They didn’t just represent Indians abroad—they represented Indianness abroad: its burdens, its beauty, its relentless echo.

As ABS folds this scroll, ears ringing with the layered voices of diaspora dinner tables and airport goodbyes, a single thought lingers: exile isn’t always political. Sometimes it’s emotional. And sometimes, you carry it inside you—even when your luggage is under the 23kg limit.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Still debating whether to return to the homeland or just write about it forever from this quiet window facing two worlds

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance