Raja Rao, R.K. Narayan, and Mulk Raj Anand: The Holy Trinity of Indian English Prose (With a Side of Spices)

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes the first stroke of a literary nation was made by a fountain pen dipped in cultural conflict.

If Indian English Literature were a three-course meal, this trio served it up with flavor, philosophy, and just enough rebellion to leave the British palate stunned. They took the Queen’s English, stirred it in kadhais of caste, culture, and coconut oil, and plated it with an unmistakable desi garnish. Behold: Raja Rao, R.K. Narayan, and Mulk Raj Anand—the first literary Avengers of Indian English prose.

Let’s imagine the three in a WhatsApp group:

Narayan: “Writing another Malgudi story. This time a goat runs for mayor.”

Anand: “Tell that goat to fight casteism too.”

Rao: “Both of you must first understand the goat is Brahman.”

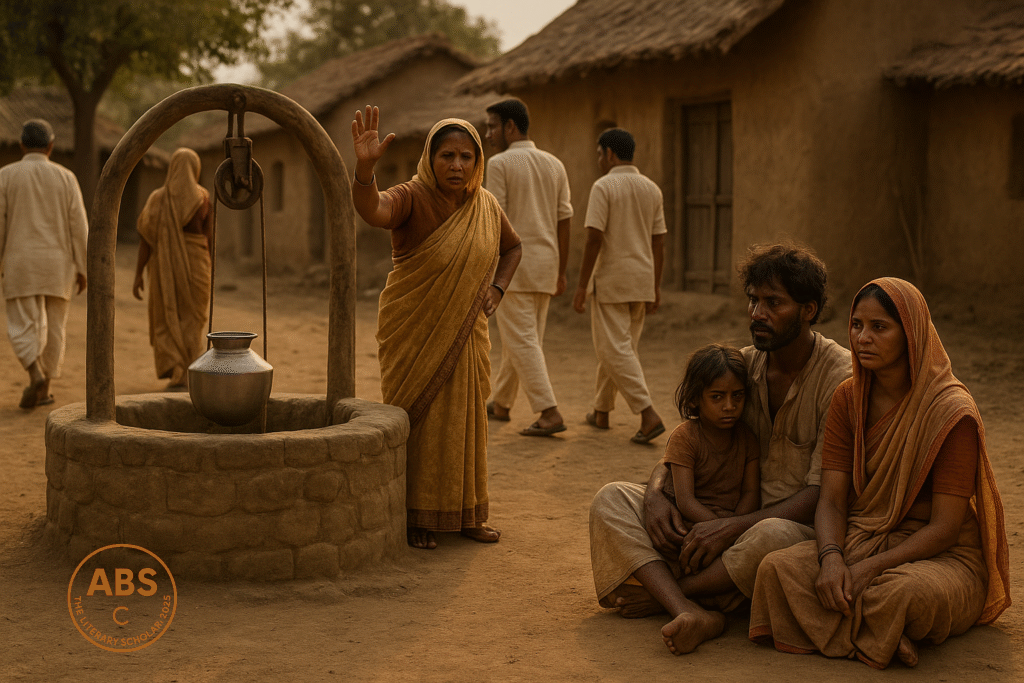

Mulk Raj Anand: Literature with a Molotov Cocktail

Mulk Raj Anand’s stories weren’t stories—they were scalding realities hurled into the lap of a polite, colonial audience who didn’t see it coming. His debut Untouchable (1935) follows one day in the life of Bakha, a toilet cleaner in a rigid caste society where touching a high-caste person could cause riots—but violence against Bakha was perfectly acceptable.

“Why are we always abused? The Sahib throws the bread at us, and they call us sons of pigs…”

Anand’s prose was thick with fury and humanity. Coolie followed a young boy’s exploitation in every corner of colonial capitalism, while Two Leaves and a Bud explored the dark tea-soaked underbelly of plantation workers’ lives. His characters didn’t sip Darjeeling—they were crushed under its economic weight.

And yet, Anand wasn’t just shouting into the void. He was crafting literature that bled compassion. His socialism wasn’t a phase—it was the foundation. He believed literature must “do” something, must “mean” something, must break the fourth wall and ask the reader: Are you comfortable? You shouldn’t be.

If Anand were a meal, he’d be a spicy chana masala served at a protest rally: hot, righteous, and guaranteed to cause heartburn—for the powerful.

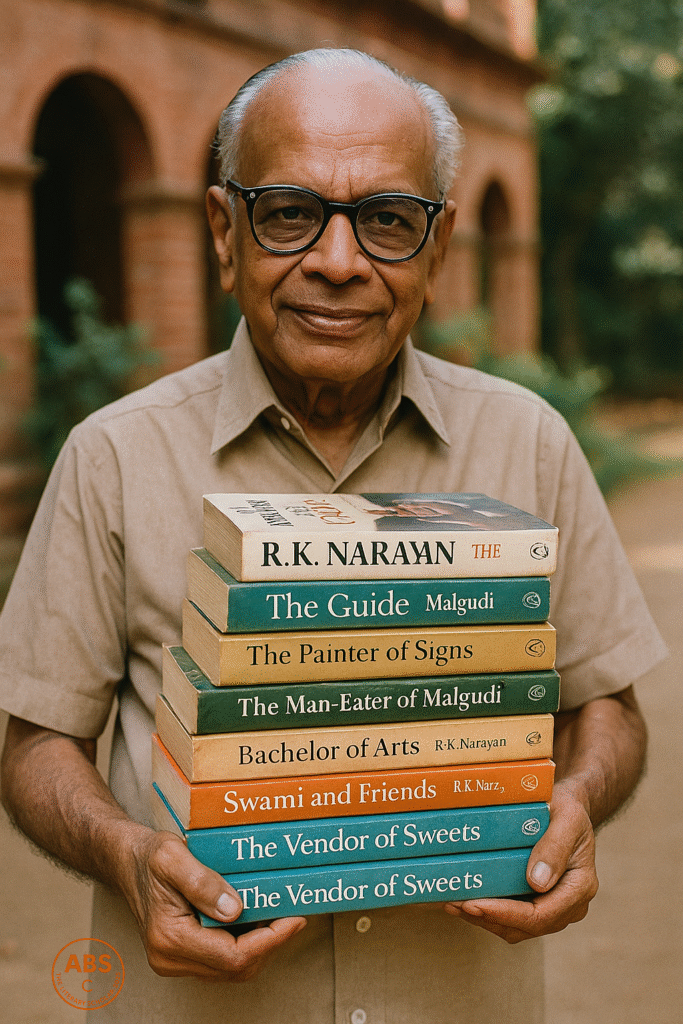

R.K. Narayan: Small Towns, Big Feels, and a Typewriter That Knew India

Now enter R.K. Narayan, who didn’t come with a torch but a gentle lamp. While Anand wrote against the system, Narayan wrote within it—like a man who opened his window, noticed the neighbour’s cow chewing the postman’s pants, and thought, “Yes. There’s a novel in that.”

Malgudi wasn’t just a fictional town—it was the beating heart of every Indian mohalla. First appearing in Swami and Friends (1935), it gave us the endearingly mischievous Swaminathan, who treated homework like a criminal conspiracy.

“Swaminathan sat on the last bench and hoped the teacher would forget his existence.”

From the childlike chaos of Swami and Friends to the metaphysical misadventures of The Guide, Narayan created a tapestry of Indian life that was comic, tragic, ironic—and always deeply human. His genius lay in understatement. In The Man-Eater of Malgudi, a simple taxidermist takes down a symbolic rakshasa with such deadpan flair, even Kafka would’ve cracked a smile.

But it’s The Guide that truly sealed Narayan’s place as the king of comic-seriousness. Raju the guide is a fraud, a prisoner, a lover, a spiritual leader—sometimes all at once. Narayan takes you on a journey from railway stations to riverbanks, love affairs to existential starvation—all with a shrug and a chuckle.

“He was not a saint. He was not even sure whether he was pretending to be one.”

Narayan’s style? Think P.G. Wodehouse moves to South India, discovers mango pickle, and starts writing between power cuts. His stories don’t demand—they invite. And once inside, you’re home.

He had no slogans, no manifestos. Just an unmatched understanding of how people stumble through life—with half-baked dreams, mistaken identities, nosy neighbors, and a whole lot of idli-sambar.

His writing is the literary version of sitting on your veranda with a cup of filter coffee, watching the world go by—and slowly realizing that everything you see is profound.

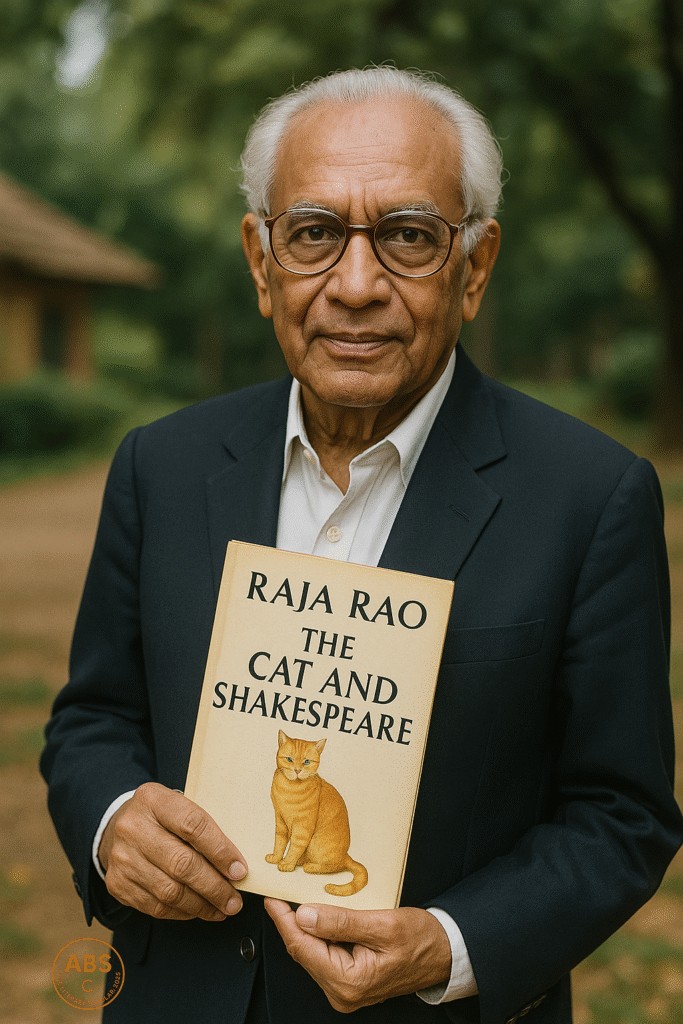

Raja Rao: Where the Vedas Meet Virginia Woolf

And then there was Raja Rao. The one with a philosopher’s frown and a yogi’s patience. He didn’t just write novels—he wrote literary Upanishads in prose.

His debut Kanthapura (1938) is Gandhi meets village gossip, narrated by an elderly woman whose storytelling meanders like a bullock cart, yet somehow carries revolution in its wheels. The language flows like an oral tradition, heavy with myth, metaphor, and mango trees.

“There is no village in India, however mean, that had not a rich sthala-purana, or legendary history.”

In The Serpent and the Rope, Rao serves a novel that doubles as a philosophical labyrinth. It’s part love story, part spiritual odyssey, part doctoral thesis. It’s like falling in love with someone at a library, and then discovering they’re also debating karma with your ancestors.

“Truth cannot be a matter of argument. It is there, like the sun.”

Rao was deeply aware that English was not his native tongue—but he made it carry Sanskrit rhythms, Vedic silences, and Indian soul. He said it best himself:

“One has to convey in a language that is not one’s own the spirit that is one’s own.”

And he did. If Anand is the fire, and Narayan the breeze, Rao is the stillness after both.

One Language, Three Revolutions

It’s impossible to overstate what these three achieved. They didn’t just write in English—they made English answer to India. Their sentences smelled of dust, sweat, curd-rice, injustice, incense, buffalo milk, and quiet rebellion.

They made it okay to have characters with names like Swaminathan and Bakha. They made it noble to write about landlords, washermen, widows, washerwomen, saints, frauds, and lovers—all without British accents or white saviors.

They created space. A literary nation within a linguistic nation.

If They Were Alive Today…

R.K. Narayan would have a blog called Notes from Malgudi, with hilarious takes on vegetable prices and emotional overreactions of cows.

Mulk Raj Anand would run a raging Twitter handle called @UntouchableNoMore, subtweeting Parliament and quoting Gorky.

Raja Rao would be on a retreat in Varanasi, releasing one cryptic Instagram reel per year—usually of sunrise over the Ganges, captioned “Not Two.”

Why We Still Read Them

Because they weren’t trying to be Indian versions of English writers. They were trying to be Indian writers—in English. And that’s far more radical. They trusted the language to adapt, to bend, to carry India without collapsing under colonial guilt.

Their stories weren’t about Empire. They were about us.

They began it all—not with a bang, but with a sentence. And a place. And a person. Swami. Bakha. Raju. They live on. Not because we owe them homage, but because we recognize ourselves in them.

As the scroll closes, ABS smiles—thinking of Swami ducking homework, Bakha staring at the out-of-reach temple steps, and Rao silently watching it all with the detachment of someone who’s read every scripture but still forgets his umbrella. Gently folding the page, ABS places the scroll among others, content in the company of three voices that made English kneel respectfully before Indian experience.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

The one who speaks in scrolls, bows to banana leaves, and always finds a story between the chai and the curd rice.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance