Or, The Man Who Gave Every Character a Moral Crisis, Then Watched Them Spiral

By ABS, the Literary Scholar, who believes Hawthorne handed out scarlet letters the way modern writers hand out plot twists—with quiet glee and moral weight.

Some authors write about love. Some write about war. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about guilt.

Not just your average “ate-too-much-chocolate” guilt, but full-blown, ankle-deep-in-Puritan-regret, divine-judgment-in-italic-font guilt—the kind you inherit with your breakfast and pass on to your children with the family Bible.

He didn’t just carry ancestral shame—he turned it into an aesthetic.

Born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts—yes, that Salem—Hawthorne grew up in the long, brooding shadow of the witch trials, with a great-great-grandfather who had a penchant for condemning people to the gallows. As damage control, Hawthorne quietly inserted a ‘w’ into his surname (as if that would fool the ghosts) and began rewriting his lineage through fiction that pulsed with ancestral trauma, symbolic torment, and spiritual claustrophobia.

Other kids had imaginary friends. Hawthorne had historical guilt and a metaphorical noose.

Guilt, Judgment, and the American Soul

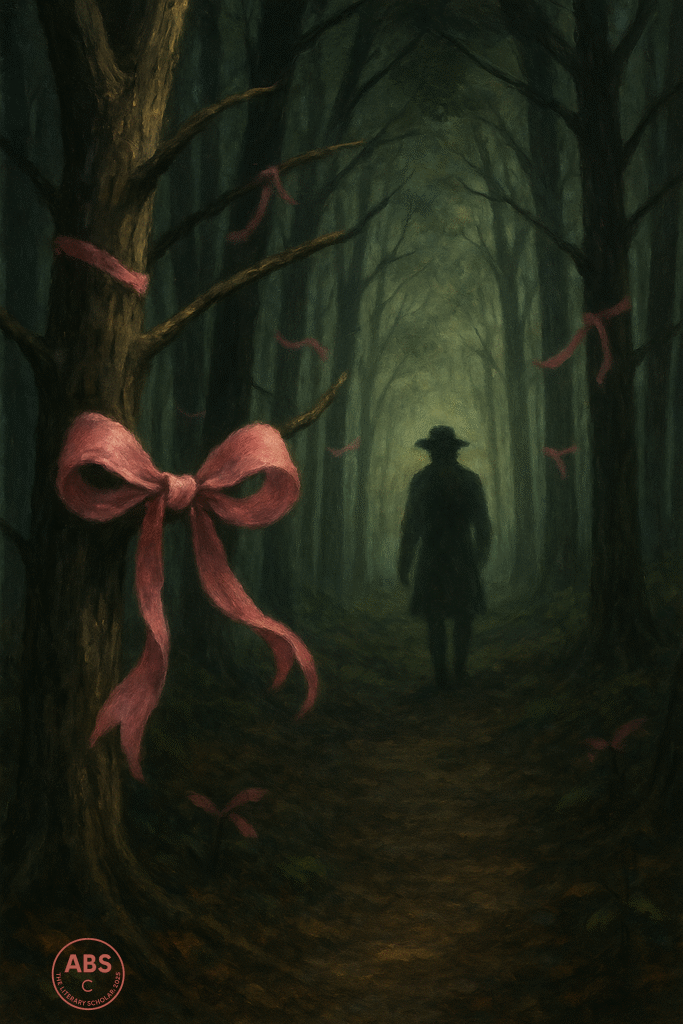

Unlike his transcendentalist friends who saw sunlight filtering through leaves as evidence of divine joy, Hawthorne saw it as the last light of innocence before the soul withered under judgment. While Emerson and Thoreau wrote about liberation, Hawthorne wrote about inner prisons—some adorned with scarlet embroidery, some shrouded in black veils, and some built into the architecture of rotting colonial mansions.

While Thoreau built a cabin to find himself, Hawthorne stayed indoors and wrote characters who barely survived themselves.

He populated his pages with tortured ministers, cursed families, suspicious townsfolk, poisoned daughters, and young men who took one existential stroll through the woods and came back permanently paranoid. Everyone in a Hawthorne story is either hiding something, suffering for hiding it, or about to be spiritually crushed under the weight of public morality.

Even his houses aren’t safe—they decay with the sins of their owners and creak with metaphor.

In Hawthorne’s world, everything’s a metaphor. Even the furniture.

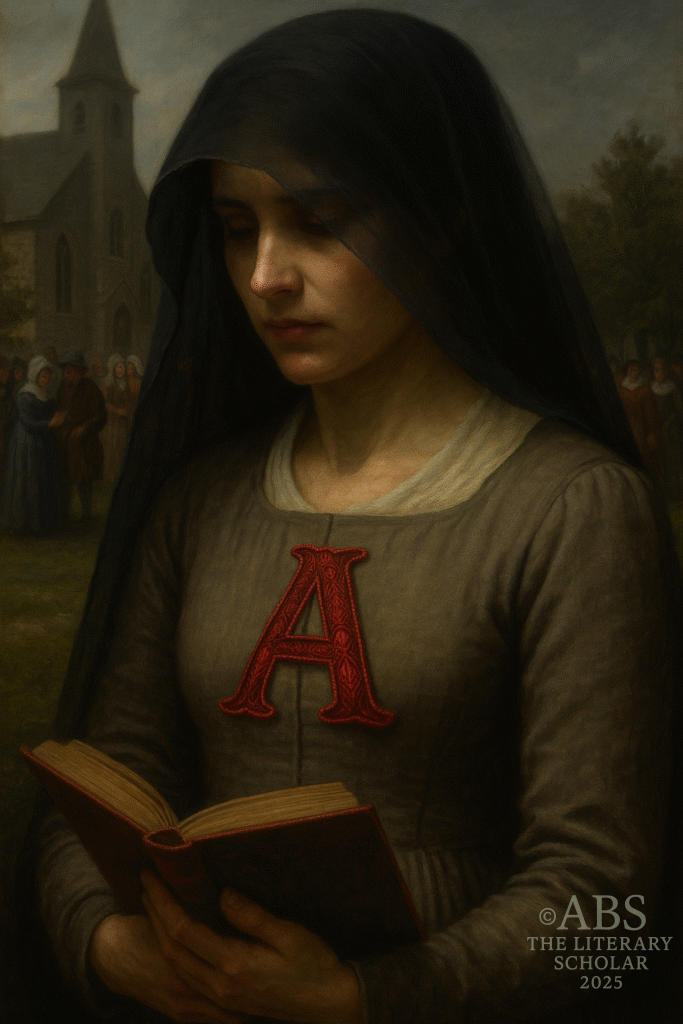

Symbolism Sewn in Sin

Adultery, in his hands, wasn’t just a scandal—it was a study in shame, strength, hypocrisy, and embroidery. The woman society branded refused to shrink. Instead, she embroidered her shame into haute couture. Dimmesdale, on the other hand, didn’t confess—he decomposed beautifully in public.

Goodman Brown, bless his troubled soul, went into the woods to find truth and came back with lifelong trust issues and a literary legacy.

And the minister who wore a veil? He never explained it, never removed it, and died just to prove a theological point. The town lost its mind. Sometimes, the sermon is the drama.

Meanwhile, in Hawthorne’s take on young love, a beautiful girl raised among poisonous plants became poisonous herself. Romeo and Juliet, if Juliet’s skincare routine could kill a horse.

His stories didn’t end. They lingered—like repressed trauma with footnotes.

The Passive-Aggressive Theology of Hawthorne

What made him brilliant wasn’t just his symbolism, though there was enough of it to make even a grad student cry. It was the way he layered sarcasm beneath the sin. The quiet rebellion sewn into Hester’s embroidery. The grim comedy of a man being destroyed by a secret everyone already suspects. The fact that he let readers stew in their own moral discomfort instead of offering resolution.

Emerson found salvation in daisies. Hawthorne found suspicion in them.

He didn’t write redemption arcs. He wrote slow, stylish emotional spirals with bad weather.

Even his punctuation felt morally conflicted.

Why Hawthorne Still Haunts Us

Why does Hawthorne still matter? Because shame still sells. Because our culture is still obsessed with appearances, virtue-signaling, and the unspoken skeletons behind curated lives. Because sin, even when rebranded as “a moment,” still echoes.

In an age of clickbait and call-outs, Hawthorne reminds us that the public scarlet letter isn’t nearly as deadly as the private one we stitch ourselves.

He diagnosed a national anxiety before Freud was even born. Every Hawthorne story carries the weight of moral dilemma, the kind that lingers long after the last page—like a sermon you pretend didn’t hit you but secretly rewired your conscience.

He didn’t just write stories—he built confessionals out of ink.

After rereading The Scarlet Letter and briefly wondering whether modern influencers are just rebranded Hester Prynnes, ABS, the Literary Scholar looked up from the annotated copy, shook their head slowly, and sighed:

Hawthorne didn’t write characters. He wrote mood boards for spiritual claustrophobia.

Then, passing a group of students desperately trying to decode the rosebush outside the prison door, ABS, the Literary Scholar whispered:

“Tell them it’s just a flower…

but also, it’s never just a flower.”

Scroll folded. Ink capped. Shame archived.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who suspects that if Hawthorne had Instagram, it would be grayscale, cryptic, and captioned “#RegretButMakeItPoetic.”

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance