By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes the real danger wasn’t in the caves—it was in the assumptions everyone walked in with)

You know you’re reading a classic when it begins with polite colonial tea and ends with the complete dismantling of friendship, trust, and any illusion that East and West will ever politely agree on whose cultural teacup is more cracked.

Enter: A Passage to India by E.M. Forster—published in 1924, two decades before independence, and still whispering in postcolonial classrooms like an unresolved diplomatic argument with literary footnotes.

It is, quite simply, a novel where nothing happens—and then suddenly, everything happens all at once in a dark cave—and no one ever emotionally recovers.

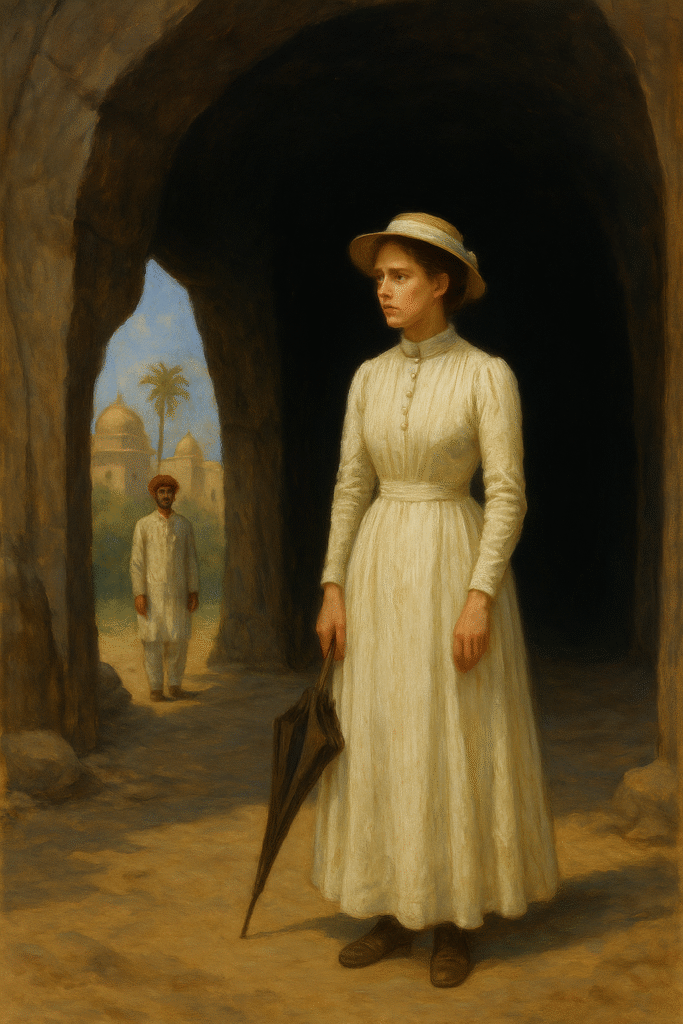

India: Seen Through a Delicate British Filter

The novel opens in the fictional city of Chandrapore, which Forster immediately informs us is unpleasant, monotonous, and suffering from a terminal case of colonial architecture. The British live in neat bungalows up the hill. The Indians sweat below.

From the start, it’s clear: the real protagonist of the novel is misunderstanding.

And the British Empire? Oh, it’s not painted in red across the map here—it’s painted in awkward silences, cultural arrogance, and brandy over boiled chicken.

Meet the Characters: An Empire’s Awkward Dinner Party

Let’s take roll call:

Dr. Aziz: Intelligent, impulsive, and proudly Indian. The man dreams of hospitality and poetry but walks into every plot twist as if it were scripted in Urdu. You want to hug him and shake him simultaneously.

Mrs. Moore: An elderly British woman who arrives in India with wide-eyed good intentions and leaves psychologically concussed by spiritual disillusionment and something terrible in a cave. She starts off quoting sympathy. She ends up quoting the echo.

Adela Quested: Young, naive, and engaged to Ronny (we’ll get to him). She wants to see the “real India,” which—spoiler alert—is not something the empire has any interest in showing her.

Ronny Heaslop: The fiancé. The Collector’s son. The very embodiment of British entitlement with a sunburn. He thinks Indians should be respected from a distance—preferably one measured in acres and policies.

Cyril Fielding: The only Brit who actually talks to Indians without looking down. A headmaster, a humanist, and—let’s be honest—the literary equivalent of Forster’s own conscience.

Together, they try to build a bridge of civility. But it turns out bridges made of colonial fragility and forced picnics tend to collapse by chapter twelve.

The Marabar Caves: Echoes, Allegories, and One Giant Literary Black Hole

Now to the famous event: the caves.

Aziz, in a rare fit of optimism, invites the British ladies on a sightseeing expedition to the Marabar Caves. No one is really prepared. The logistics are a mess. The servants get lost. The picnic goes cold. And then… something happens.

“There is an echo… entirely devoid of distinction. Whatever is said, the same monotonous noise replies.”

This echo isn’t just sound. It’s metaphysical chaos. It reduces words to nonsense. It shakes meaning loose from language. It leaves Mrs. Moore spiritually stunned and Adela psychologically scrambled.

Adela emerges from the caves claiming Aziz has assaulted her.

But has he?

Even she’s not sure.

No one saw anything. Nothing is clear. No crime is proven. And yet, an entire colonial empire is suddenly certain of guilt, because certainty, it turns out, is far easier than justice.

The Trial: Guilt, Gaslighting, and Imperial Righteousness

What follows is not a court case—it’s a colonial circus. Aziz is arrested. Fielding defends him. Adela wavers. The British rally with pompous outrage.

“We’re not in India to behave as if we were in a county cricket match.”

Translation: We’re here to rule, not question our superiority.

Adela, during the trial, suddenly retracts her accusation. Not because she’s noble, but because she realizes she may have imagined it all. Or been overwhelmed. Or echoed out of clarity.

Aziz is acquitted. The empire simmers in fury. And no one celebrates—because the damage has already been done.

Friendship, Fracture, and Forster’s Final Shrug

Post-trial, Aziz and Fielding try to remain friends. But colonialism, like a nosy relative, never lets people stay uncomplicated.

Aziz becomes more nationalist. Fielding, still a rational liberal, can’t relate.

“Why can’t we be friends now?”

“It’s impossible… until India is free.”

And that’s it.

The novel closes with no resolution, no embrace, and no inspirational speech—just the knowledge that friendship under empire is not a relationship, but a contradiction.

What Was the Echo, Really?

Forster never tells us.

That’s the brilliance. The echo in the cave becomes a metaphor for empire, for god, for fear, for the limits of language, and for everything the British refused to understand about India.

It is the echo of indifference, the sound made when meaning falls apart. And in the face of that, everyone—British or Indian—is left rattled, uncertain, and oddly alone.

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, rolls up a British Empire map, throws it into the Marabar Cave, listens to the soundless echo return, and finally concludes, “Ah yes, exactly what I thought: nothing.”

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who still believes some friendships were never meant to survive empire)

(Still echoing back Forster’s question: “Can the colonizer and the colonized ever meet on equal ground?”)

(And still suspicious of caves that claim to contain truth)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance