By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who has always suspected that Edna Pontellier’s true sin was having a soul before it was socially scheduled)

It begins on a porch. It ends in the sea. And somewhere between parasols, piano music, and polite dinner parties, Edna Pontellier realizes what every well-bred Victorian woman was trained not to say out loud: I want out.

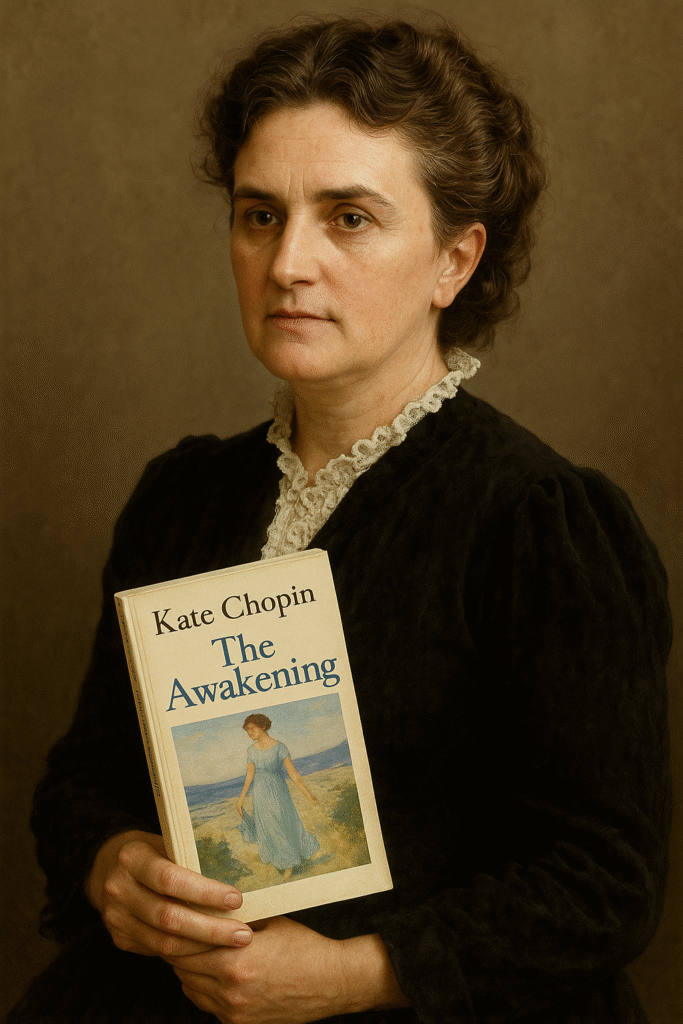

Welcome to Kate Chopin’s The Awakening (1899)—the original feminist grenade disguised as a story about a summer holiday. The novel was written at a time when a woman’s emotional range was expected to oscillate between grateful docility and pleasing silence. Instead, Chopin handed her protagonist longing, lust, and a desire to live beyond lace and lemonade.

The result? Scandal. Ban. Obscurity. And then—vindication. Because now, over a century later, The Awakening is not just a classic. It’s the patron saint of every woman who’s ever looked at her perfect life and muttered, “I didn’t ask for this.”

Edna Pontellier: Wife, Mother, Existential Crisis in a Silk Gown

Edna begins the novel as Mrs. Leonce Pontellier, wife to a respectable New Orleans businessman who believes “a woman should always be amiable—and preferably available.” Her children adore her. Her social circle approves of her. She’s beautiful, affluent, and utterly trapped.

“She was not a mother-woman.”

Translation: She didn’t find self-annihilation in service to her children. She didn’t melt at the sight of booties or burst into a symphony of coos. In a world where womanhood was synonymous with motherhood, this made Edna… unnatural.

And therein lies the trouble.

Because Edna doesn’t hate being a mother. She just refuses to disappear into it. She wants to be more than someone else’s emotional infrastructure.

She wants to be herself—even though she’s not entirely sure who that is.

Creole Summers and Dangerous Ideas

While vacationing at Grand Isle (because what’s a breakdown without ocean views), Edna meets the Creoles—flirtatious, dramatic, and deliciously expressive. And there, in the lazy lull of summer, Edna meets Robert Lebrun.

He’s charming. He’s attentive. He listens. Which, in Edna’s world, is roughly equivalent to seduction.

They spend time talking, walking, and not-quite-touching. It’s all very will-they-won’t-they-except-they-won’t. But for Edna, Robert awakens a hunger—not just for romance, but for freedom. For something unscripted.

“The voice of the sea is seductive, never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring.”

That voice? It’s not about Robert. It’s about Edna’s soul finally removing its corset.

Back in New Orleans: Domesticity’s Cold Embrace

When Edna returns to New Orleans, she starts disrobing—symbolically and socially. She abandons her at-home reception days (scandalous!), ignores her husband’s instructions (unthinkable!), and eventually moves into the “pigeon house”, a small space she pays for herself.

It’s not about real estate. It’s about rebellion. Edna chooses solitude over servitude. Independence over etiquette.

And in between painting, piano concerts, and a rather sensual affair with Alcee Arobin (because existentialism goes down easier with cheekbones), Edna starts to bloom.

Briefly. Tragically.

Because freedom, for Edna, doesn’t come with a roadmap. It comes with isolation. No one truly understands her—not Robert, not Arobin, not even Madame Reisz, the fierce, unmarried pianist who acts as Edna’s spiritual midwife.

Edna is not seeking lovers. She’s seeking herself. And in a society allergic to autonomous women, that search leads her not forward—but inward.

The Sea, The Ending, and the Literary Riptide

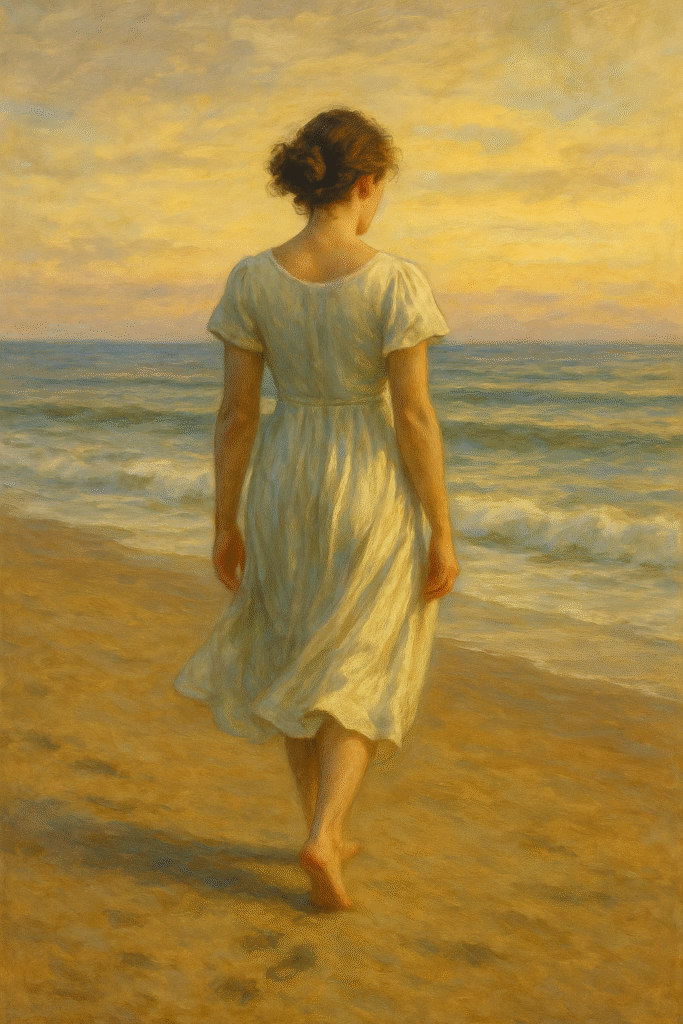

And then comes that final scene—Edna walking into the sea.

Not as a sacrifice. Not as a punishment. But as an act of refusal.

“She felt like some new-born creature, opening its eyes in a familiar world that it had never known.”

The water becomes her only sanctuary. It is the only space where her body and mind belong solely to her. The waves do not ask for dinner. They do not call her “mama.” They do not correct her or caution her. They just hold her.

Is it suicide? Is it transcendence? Is it the only ending patriarchy left her?

Yes.

Why It Was Banned, Burned, and Eventually Canonized

When The Awakening was published in 1899, the critical response was an elegant mix of moral horror and polite misogyny. Edna was labeled unnatural. The book was deemed “unwholesome.” Kate Chopin’s literary reputation tanked faster than you can say “free-thinking woman with sexual agency.”

And yet… The Awakening would not drown.

Over time, readers—especially women—began to recognize Edna’s ache as their own. The longing to be seen, to exist outside of roles, to be neither wife nor muse nor mother—but person.

Today, it’s taught, quoted, studied, and revered. Not because Edna is a hero. But because she is devastatingly human.

The Real Awakening: When You Realize You Don’t Belong to Anyone

Chopin’s genius lies not in writing about a woman who has an affair. That’s been done. She wrote about a woman who starts asking the questions patriarchy cannot answer.

What if I don’t want to sacrifice myself for my children?

What if I want solitude more than romance?

What if freedom is not happiness—but simply space?

There are no tidy takeaways. No redemption arcs. Just the echo of Edna’s choice, rippling through literature like a bell that won’t stop ringing.

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, picks up a silver teapot, stares into its polished surface, and places it quietly back on the shelf—not because it isn’t beautiful, but because it was never meant to hold her reflection.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who knows Victorian wallpaper and gender roles peel at the same rate)

(Still swimming against the tide with pockets full of pages)

(And who believes Edna Pontellier wasn’t selfish—she was just early)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance