“Earnest Lies and Serious Nonsense: Oscar Wilde’s Comedy of Perfect Pretence”

A comedy where names matter more than character, love begins with a misunderstanding, and sincerity is strictly optional.

ABS BELIEVES

Society prefers well-dressed lies to badly spoken truths.

Wilde laughs at morality because he understands it too well.

In a world obsessed with appearances, pretending is the most honest act.

OSCAR WILDE

A man who dressed like art, spoke like epigrams, and mocked society while it applauded

Oscar Wilde did not enter literature quietly. He arrived dressed to be noticed, speaking in sentences already polished for quotation, and behaving as though life itself were a stage play written for his amusement. Born in 1854 in Dublin, Wilde grew up surrounded by intellect, ambition, and a healthy disrespect for dullness. His parents were formidable personalities, and Wilde inherited not only intelligence but the dangerous confidence that comes with knowing one’s own brilliance.

He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and later at Oxford, where he perfected what would become his lifelong philosophy: art matters, beauty matters, and seriousness is often overrated. Wilde believed that life should imitate art, not the other way around, a principle he followed with impressive consistency, even when it became inconvenient.

Wilde was a master of contradiction. He mocked morality yet understood it intimately. He ridiculed society while craving its admiration. He exposed hypocrisy while performing flamboyance with theatrical precision. And through it all, he wrote.

Oscar Wilde’s fame rests primarily on his plays, which remain some of the sharpest comedies in the English language. These plays are not loud. They do not moralise. They smile politely while dismantling entire social systems.

In Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde turns a seemingly respectable drawing room into a battlefield of reputation, gossip, and judgement. The play exposes how quickly society condemns women and how eagerly it forgives men. Wilde uses wit as camouflage, allowing serious questions about morality, marriage, and female autonomy to slip past the audience unnoticed—until it is too late.

A Woman of No Importance does exactly what its title promises: it pretends to be about nothing while quietly exposing everything. Here, Wilde attacks Victorian double standards, particularly the way society punishes women for moral lapses while celebrating men for the same behaviour. The play is filled with sparkling dialogue and savage irony, proving once again that Wilde’s lightness is deliberate, not careless.

Then comes An Ideal Husband, a play that politely suggests that ideals are exhausting and honesty is rarely practical. Wilde examines politics, marriage, reputation, and blackmail, all while maintaining the illusion of harmless entertainment. In Wilde’s world, virtue is negotiable, secrets are currency, and society prefers appearances over truth—an idea he will later perfect.

And finally, there is The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde’s most famous and most dangerous comedy. On the surface, it is nonsense. Beneath that nonsense lies a precise satire of Victorian manners, identity, romance, and morality. With characters who fall in love with names rather than people and societies that care more about handbags than human beings, Wilde creates a masterpiece of laughter that refuses to reform anyone.

Beyond the stage, Wilde also ventured into fiction, most notably with The Picture of Dorian Gray, a novella that scandalised Victorian readers and secured Wilde’s immortality. In it, Wilde explores beauty, corruption, desire, and the terrifying consequences of living without moral accountability. While critics accused the novel of immorality, Wilde smiled and reminded them that books are not moral or immoral—only well or badly written.

“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written.”

That sentence alone tells you everything about Wilde’s literary philosophy.

Wilde also wrote essays, poems, fairy tales, and critical works. His fairy tales, including The Happy Prince and The Selfish Giant, reveal a softer, more compassionate Wilde—one deeply aware of suffering, injustice, and emotional cost. Even here, sentiment never becomes sentimental. Wilde always retains control.

But Wilde’s greatest legacy may be his style.

Oscar Wilde wrote dialogue that sounds effortless but is ruthlessly constructed. His characters speak in epigrams, paradoxes, and reversals. He takes moral clichés and turns them inside out. He makes society laugh at itself before it realises it has been mocked.

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

“I can resist everything except temptation.”

“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

These are not decorative quotes. They are compressed philosophies.

Wilde’s wit was not accidental. It was a weapon. In an era obsessed with restraint, he exaggerated elegance. In a culture addicted to respectability, he performed flamboyance. In a society terrified of scandal, he turned scandal into art.

Of course, society eventually punished him for it.

Wilde’s later life was marked by trials, imprisonment, and public disgrace, a brutal reminder that Victorian tolerance had strict limits. The same society that applauded his plays turned vicious when he stopped playing the acceptable role. Wilde endured prison, exile, and poverty, yet even in suffering, his intelligence never abandoned him.

He died in 1900, famously remarking that either the wallpaper would go or he would.

Oscar Wilde remains enduring because he understood something essential: societies change slowly, but hypocrisy is timeless. His plays still work because manners still perform morality. Appearances still matter more than truth. And people still prefer to laugh rather than reflect.

Wilde did not want to be taken seriously.

He wanted to be taken accurately.

And more than a century later, we are still quoting him, still laughing with him, and still slightly uncomfortable—exactly as he intended.

Where seriousness is mocked, sincerity is suspicious, and Victorian respectability gets roasted politely

Oscar Wilde did not write The Importance of Being Earnest to improve morals. He wrote it to expose how easily society confuses manners with morality. This is not a comedy about goodness. It is a comedy about good appearances.

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

Victorian England adored rules, reputations, and rigid respectability. Wilde adored making all three look ridiculous without raising his voice. In Earnest, everyone is proper, nobody is honest, and everything works out beautifully. That is not optimism. That is satire at its most refined.

“If one tells the truth, one is sure, sooner or later, to be found out.”

At the heart of this glittering nonsense lies a dangerous question:

What if being “earnest” is not a virtue, but a role people perform to survive society?

Jack invents a brother to escape responsibility.

Algernon invents an invalid friend to avoid boredom.

Love arrives before familiarity. Engagements precede understanding.

And character matters far less than whether your name sounds respectable enough to marry.

“A man who marries without knowing Bunbury has a very tedious time of it.”

Wilde never preaches. He lets language do the damage. His epigrams smile while cutting, amuse while accusing, and entertain while quietly dismantling Victorian hypocrisy. The laughter comes first. The discomfort follows later.

“We live, I regret to say, in an age of surfaces.”

This scroll does not summarise the play. It unpacks the joke, examines the disguises, and enjoys the absurdity with full awareness of what Wilde is really mocking.

Because Wilde never asked us to be sincere.

He asked us to be clever enough to recognise the performance.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST

A complete story-summary told seriously enough to be funny

Oscar Wilde opens his most famous comedy not with drama, danger, or destiny, but with tea. That alone tells you everything. In Wilde’s world, crises arrive politely, lies are upholstered, and moral collapse happens over cucumber sandwiches.

The story begins in London, where Jack Worthing pretends to be someone else and feels only mildly uncomfortable about it. In the countryside, Jack is responsible, upright, and guardian-like. In the city, he becomes “Ernest,” a name that conveniently excuses irresponsibility. This is not duplicity born of desperation. It is duplicity born of convenience, and Wilde makes sure we understand that this kind of lying is not frowned upon. It is practically encouraged.

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

Jack’s double life is exposed almost immediately by his friend Algernon Moncrieff, a man who treats morality the way others treat weather: something to complain about, never something to obey. Algernon has perfected a system called Bunburying, which involves inventing an imaginary friend who is permanently ill and endlessly useful. Whenever social obligations become tiresome, Bunbury falls sick. Algernon rushes to his side. Society applauds his sensitivity.

“I have invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury.”

This is Wilde’s first punchline and his thesis statement. Deception, when dressed properly, is admirable.

The men’s conversation is interrupted by romance, which in Wilde’s hands is never about people but about ideas. Jack wishes to marry Gwendolen Fairfax, a woman who loves him passionately for one deeply philosophical reason: she adores the name “Ernest.” Not the man. The name. Jack’s personality barely registers. His sincerity is irrelevant. His name, however, is non-negotiable.

“My ideal has always been to love someone of the name of Ernest.”

Here Wilde begins his demolition of romantic idealism. Love is not blind. It is shallow, specific, and absurdly stubborn.

Enter Lady Bracknell, Gwendolen’s mother and the embodiment of Victorian authority. Lady Bracknell does not shout. She interrogates. Marriage, to her, is not about affection but about income, ancestry, and social safety. When Jack reveals that he was found as a baby in a handbag at Victoria Station, Lady Bracknell reacts not with sympathy but horror.

“To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

With that line, Wilde makes his position clear. In this society, tragedy is forgivable. Improper origins are not.

Jack is rejected. Engagements are postponed. Everyone remains civil.

The action then shifts to the countryside, where Cecily Cardew, Jack’s young ward, lives a life powered entirely by imagination. Cecily keeps a diary not to record events, but to invent them. She has already fallen in love, quarrelled, reconciled, and become engaged—on paper—to Ernest Worthing, whom she has never met. This is romance perfected: all feeling, no interference from reality.

“I keep a diary in order to enter the wonderful secrets of my life.”

Algernon arrives pretending to be Ernest. Not because he must. Because he can. Cecily welcomes him as if destiny itself has finally shown up on time. Their romance proceeds at alarming speed because it has been emotionally rehearsed in advance.

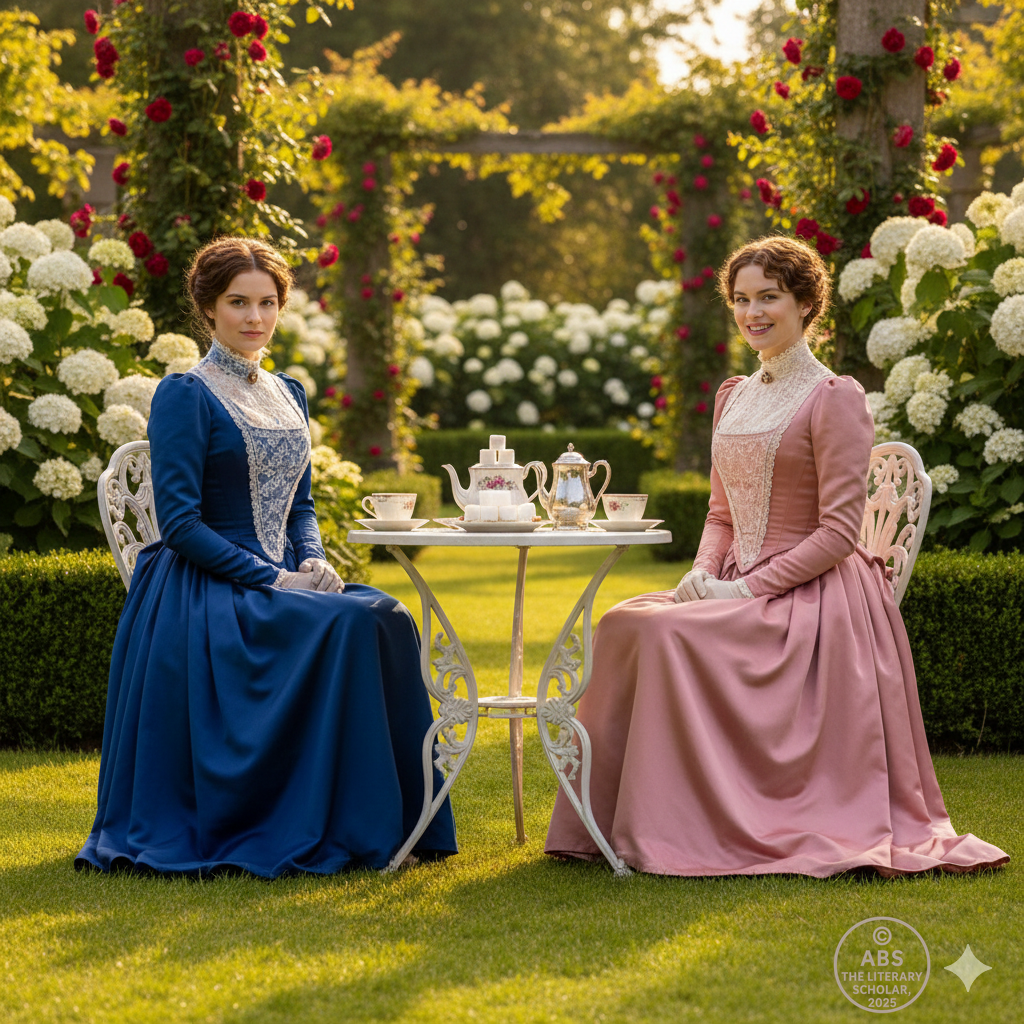

Then comes one of the most famous scenes in English comedy: Gwendolen meets Cecily.

The meeting begins with exaggerated politeness. Compliments are exchanged. Smiles sparkle. Tea is served. And beneath every courteous phrase, a blade is sharpened. Both women believe they are engaged to Ernest Worthing. Neither is willing to compromise.

Sugar becomes a weapon. Tea becomes a battlefield. Politeness becomes aggressive sport.

“Your Christian names are still an insuperable barrier.”

When the truth emerges—that neither man is actually named Ernest—the women react not with grief, but irritation. They are not heartbroken. They are annoyed that their ideals have been inconvenienced. The men confess their lies not out of remorse, but because it has become socially exhausting to maintain them.

Truth enters the room reluctantly.

The final movement of the story returns us to Lady Bracknell, who arrives like an official stamp of approval. She brings with her order, scrutiny, and the comforting rigidity of social rules. Emotions are temporarily set aside. Background checks resume.

And then Wilde delivers his most ridiculous stroke of genius: the handbag.

Miss Prism, Cecily’s governess and a monument to suppressed propriety, confesses that years ago she accidentally misplaced a baby—in a handbag—at Victoria Station. That baby, of course, was Jack. The revelation restores Jack’s lineage, not his character. But character was never the problem.

“A handbag?”

The moment is absurd, miraculous, and perfectly on point. Identity is not discovered through reflection or growth. It is recovered through luggage.

Jack learns that his real name was, in fact, Ernest all along. This satisfies everyone. Gwendolen is pleased. Cecily is relieved. Society breathes again. The lies are forgiven not because they were wrong, but because they no longer matter.

Even Miss Prism and Dr. Chasuble, the local clergyman and long-time admirer, are rewarded with romance, proving that repression, too, deserves its happy ending.

Jack concludes the play with a line that seals Wilde’s satire forever:

“I have now realised for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest.”

It is the perfect ending because it means nothing and everything at once. Jack has not become sincere. He has simply become acceptable.

And that is Wilde’s final joke.

The play ends happily because nothing truly changes. Society remains obsessed with appearances. Romance remains a fantasy. Honesty remains optional. And the audience, laughing comfortably, realises—perhaps too late—that they have just applauded a play that dismantled every value they pretend to hold dear.

In The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde does not ask us to be truthful.

He asks us to be clever enough to notice the lie.

And then he hands us tea.

ACT I — The Art of Lying Respectably

(A complete story-summary of Act I)

The play opens in London, in a drawing room so comfortable that nothing truly honest could survive there. Tea is being served, cucumber sandwiches are being consumed with alarming seriousness, and Algernon Moncrieff, a young man of leisure and remarkable moral flexibility, is doing what he does best: enjoying himself without the slightest intention of improving.

Into this pleasant idleness steps Jack Worthing, Algernon’s friend, who appears respectable enough but carries with him a secret so common in Victorian society that it barely counts as scandal. Jack lives two lives. In the countryside, he is earnest, responsible, and guardian to a young girl named Cecily. In the city, he transforms into someone else entirely, a man named Ernest, who conveniently allows him to misbehave without consequences.

This double life is not revealed through confession or guilt. It is exposed through something far more dangerous: a cigarette case.

Algernon discovers the case accidentally, reads the inscription inside, and immediately senses trouble. The case reveals that Jack is known by different names in different places. This is not a dramatic revelation. It is a conversational inconvenience.

“You have invented a very useful younger brother called Ernest.”

Jack attempts to explain. Ernest, he claims, is a wayward brother whose bad behaviour forces Jack to travel frequently to London. Algernon, impressed rather than offended, recognises a fellow artist of deception. In fact, he confesses that he has perfected a similar strategy of escape called Bunburying.

Bunbury is an imaginary invalid friend who is always ill at precisely the right moment. Whenever Algernon wishes to avoid social obligations, Bunbury requires immediate attention. Society, touched by this display of concern, never questions the arrangement.

“I have invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury.”

Here, Wilde sets the rules of his world. Lying is not immoral. Lying badly is.

The conversation shifts, as it inevitably must, to romance. Jack announces that he wishes to marry Gwendolen Fairfax, Algernon’s cousin. Algernon reacts not with excitement but suspicion, because in Wilde’s universe, love is never simple and rarely sincere.

When Gwendolen enters, she brings with her elegance, confidence, and a deeply irrational conviction: she is determined to marry a man named Ernest. Not because Ernest is virtuous. Not because Ernest is kind. But because the name itself inspires absolute trust.

“The name of Ernest inspires absolute confidence.”

Jack is alarmed. He loves Gwendolen, but he is not actually Ernest. He considers honesty briefly and dismisses it almost immediately. Instead, he decides that the sensible solution is to change his name.

Love, in this act, is not about people. It is about labels.

Then enters Lady Bracknell, Gwendolen’s mother and the true authority of the play. Lady Bracknell does not believe in romance. She believes in background checks. She interrogates Jack with clinical precision, asking about income, property, habits, and lineage. Jack answers well until he reaches the small matter of his birth.

Jack explains that he was found as a baby in a handbag at Victoria Station.

Lady Bracknell is horrified.

“To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

This line does not shock anyone on stage. That is the point. In this society, being an orphan is not tragic. It is socially unacceptable. Jack is rejected—not because of who he is, but because of where he comes from.

Engagement is forbidden. Respectability must be preserved.

By the end of Act I, nothing terrible has happened, and everything important has been exposed. Both men lie comfortably. Both women love ideal names rather than actual people. Authority polices origins, not morality. And truth remains optional, provided one is polite about avoiding it.

The audience laughs, because the drawing room is charming.

Wilde smiles, because the joke has landed.

ACT II — Love Written in Advance

(A complete story-summary of Act II)

Act II takes us away from London’s upholstered lies and into the countryside, where fresh air is supposed to bring honesty. Wilde, of course, does not believe this for a second. In the country lives Cecily Cardew, Jack Worthing’s young ward, and she is proof that imagination can be far more dangerous than deceit.

Cecily is intelligent, lively, and deeply romantic in the most impractical way possible. She keeps a diary, but not as a record of life. Her diary is a creative document, a place where emotions are decided in advance and reality is expected to catch up later.

“I keep a diary in order to enter the wonderful secrets of my life.”

Cecily has long been in love with Ernest Worthing, Jack’s imaginary brother. She has never met him, but that has not stopped her from imagining a complete relationship. In her diary, Ernest has proposed. They have quarrelled. They have reconciled. He has even promised to reform. The only thing missing is Ernest himself, which Cecily treats as a minor inconvenience.

Enter Algernon Moncrieff, arriving in the countryside pretending to be Ernest Worthing. This is not an act of necessity. It is an act of opportunity. Algernon discovers that he has walked directly into a romance already in progress and decides, quite sensibly by Wildean standards, to accept his role.

Cecily greets him warmly, as though he has merely been late, not imaginary. Algernon is delighted. For once, deception requires no effort.

“You are the very person I was expecting.”

Cecily explains her expectations calmly. Ernest, she believes, is wicked but reformable, and she finds that deeply attractive. Algernon, sensing a romantic challenge, immediately declares his intention to reform at once. In this world, moral transformation is as easy as changing one’s name.

Their engagement happens swiftly. Cecily accepts Algernon’s proposal with enthusiasm, produces her diary as proof that they have been engaged for months, and gently informs him of the fact. Algernon is briefly startled but recovers quickly. Being engaged retroactively is, after all, extremely convenient.

Meanwhile, Jack Worthing arrives dressed in black, announcing that his brother Ernest has died suddenly in Paris. This is meant to end his double life permanently. Unfortunately, Algernon is very much alive and pretending to be Ernest at that very moment.

Complications multiply.

Soon after, Gwendolen Fairfax arrives from London, convinced that she is engaged to Ernest Worthing. She meets Cecily, who is equally convinced of the same thing. What follows is one of the most exquisitely restrained confrontations in comic literature.

At first, the women are excessively polite. Compliments are exchanged. Tea is served. Smiles are perfectly controlled.

Then the topic of engagement arises.

Both women insist on the name Ernest. Neither is willing to compromise.

“Your Christian names are still an insuperable barrier.”

Politeness becomes weaponised. Sugar is passed pointedly. Tea is poured with intention. Each woman remains impeccably civil while clearly preparing to destroy the other emotionally.

When the truth finally emerges—that neither man is actually named Ernest—the women react not with despair, but irritation. They are not heartbroken. They are offended that their ideals have been inconvenienced.

The men confess their lies, not out of guilt, but because maintaining them has become socially exhausting.

The engagements are broken. The atmosphere grows tense. And yet, no one truly questions the system that produced the deception in the first place.

By the end of Act II, imagination has collided with reality and refused to apologise. Love has been exposed as a matter of names, not nature. Diaries have proven more powerful than truth. And romance, far from being ruined, simply waits for a more convenient explanation.

Wilde leaves us here deliberately unsettled.

Because in this world, illusion is not the enemy of love.

Reality is.

ACT III — The Handbag That Fixed Everything

(A complete story-summary of Act III)

Act III begins where all respectable Victorian problems must end: indoors, with authority present and emotions firmly kept under control. Romance has gone wrong, engagements have collapsed, and yet nobody is emotionally devastated. They are merely inconvenienced. This is Wilde’s world, after all, where feelings are optional but propriety is compulsory.

Jack and Algernon stand exposed as impostors. Their lies are now public. And yet, remarkably, no one is particularly shocked. What concerns everyone far more is not that the men lied, but that the lies have caused administrative confusion.

The women, Gwendolen and Cecily, are disappointed, but not because they were deceived. They are disappointed because the men are not named Ernest. That detail, to them, remains crucial.

“My ideal has always been to love someone of the name of Ernest.”

Jack, sensing that moral reform will not solve this situation, decides on a more practical solution. He announces his intention to be christened immediately. If society demands a name rather than sincerity, then a name it shall have.

At this point enters Lady Bracknell, the true judge and jury of the play. She does not arrive to comfort her daughter or resolve emotional distress. She arrives to investigate. For Lady Bracknell, love is acceptable only after background verification.

Her attention soon turns to Cecily, who, unlike Jack, possesses what Victorian society truly respects: money. Upon discovering Cecily’s fortune, Lady Bracknell instantly approves of her as a suitable match for Algernon. Love, it turns out, becomes much easier when finances cooperate.

Jack, however, still faces a problem. Lady Bracknell remembers him well. He is the man with no parents and an unfortunate history involving public transport luggage.

Jack attempts once again to explain his origins. He was found as a baby, placed accidentally in a handbag at Victoria Station. Lady Bracknell is unimpressed.

“A handbag?”

This single word carries the full weight of Victorian horror. It is not abandonment that troubles her. It is improper storage.

Just when the situation appears hopeless, Wilde performs his most audacious trick. Enter Miss Prism, Cecily’s governess, a woman of rigid morality, suppressed emotion, and impeccable seriousness. Lady Bracknell recognises her immediately and demands an explanation for a long-ago incident involving a missing baby.

Miss Prism, visibly shaken, confesses. Years earlier, distracted by her love of intellectual improvement, she accidentally placed a manuscript in a baby carriage and the baby in a handbag. That handbag was left at Victoria Station.

The room freezes.

Jack realises, with growing astonishment, that he is that baby.

The revelation is ridiculous, improbable, and absolutely perfect. Wilde does not offer emotional reunion or existential reflection. He offers social validation. Jack is no longer a problem because his origins have been explained.

Even better, Lady Bracknell reveals that Jack’s father was her own brother. Jack is not only respectable. He is related.

Identity, in this world, is restored not through character, but through lineage paperwork.

Jack’s final discovery seals the joke completely. He learns that his real name was always meant to be Ernest.

“I have now realised for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest.”

The line is a masterpiece of irony. Jack has not become morally earnest. He has simply become correctly labelled. That is enough.

With the name issue resolved, all objections vanish instantly. Engagements are approved. Romance resumes. Society relaxes.

Even Miss Prism is rewarded with affection from Dr. Chasuble, proving that repression, too, deserves compensation.

The play ends happily not because anyone has changed, but because everything now looks right. Lies are forgiven. Truth is irrelevant. Appearances are restored.

Wilde closes the curtain gently, having exposed an entire social system without ever raising his voice.

Because in The Importance of Being Earnest, the real miracle is not love, honesty, or reform.

It is this:

If you are named correctly,

born acceptably,

and presented politely,

society will forgive absolutely everything.

And it will applaud while doing so.

WHAT WAS OSCAR WILDE REALLY SAYING IN THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST?

Oscar Wilde did not write The Importance of Being Earnest to tell a story. He wrote it to expose a society that mistook performance for virtue and appearance for morality. And he did it in the only way such a society would tolerate: by making it laugh.

At first glance, the play looks harmless. No villains. No tragedy. No consequences. People lie, identities shift, engagements break and resume, and everyone ends up happy. That is precisely the problem Wilde wants us to notice.

This is a society where nothing truly matters except how things look.

Wilde’s Victorian audience lived under strict moral codes. Respectability was everything. Reputation was sacred. But Wilde understood something uncomfortable: these values were rarely about ethics. They were about control, convenience, and class. So instead of attacking morality directly, he mocked its performance.

In Earnest, no one is punished for lying. Jack lies. Algernon lies. They lie easily, repeatedly, and creatively. And society not only forgives them, it barely notices. Why? Because the lies are polite.

Wilde is showing us that Victorian morality did not oppose dishonesty. It opposed inconvenience.

1. Society Values Appearances Over Truth

The central joke of the play is painfully simple: names matter more than nature. Gwendolen and Cecily do not fall in love with men. They fall in love with the idea of “Ernest.” The name itself becomes a moral credential.

This is Wilde’s satire of social labels. In Victorian society, titles, family names, and appearances carried more weight than integrity. If you looked respectable, you were respectable. If you sounded moral, you were moral.

Truth becomes irrelevant.

That is why Jack’s final transformation is so bitterly funny. He does not become honest. He becomes properly named. And suddenly, everything is forgiven.

Wilde is saying: society does not want sincerity. It wants correct packaging.

2. Pretence Is Not the Exception. It Is the System.

Bunburying is not just a joke. It is a metaphor.

Jack invents Ernest. Algernon invents Bunbury. Cecily invents a love story. Miss Prism invents seriousness. Lady Bracknell invents morality. Everyone is pretending, but pretending within acceptable boundaries.

Wilde is not condemning individual dishonesty. He is exposing institutional hypocrisy.

Victorian society demanded rigid moral behaviour publicly, while quietly encouraging escape routes privately. Bunburying becomes survival. Double lives become necessary. Hypocrisy becomes polite.

Wilde’s point is ruthless:

A society that demands perfection forces dishonesty.

3. Love Is Reduced to Social Fiction

Romance in Earnest is deliberately absurd. Engagements happen before acquaintance. Love is declared before understanding. Diaries record emotions that have never occurred.

This is not because Wilde hates love. It is because he is mocking romantic idealism shaped by social expectations. Love becomes a script people follow, not a feeling they discover.

Marriage, especially, is stripped of sentiment and revealed as a social transaction. Lady Bracknell’s interrogation turns romance into an application form. Money, lineage, and respectability matter. Emotion does not.

Wilde is showing how society commodifies love, turning it into another performance of correctness.

4. Authority Is Shallow but Absolute

Lady Bracknell is one of Wilde’s greatest creations because she is terrifying precisely because she is calm. She does not shout. She does not threaten. She simply decides.

She represents institutional authority: aristocracy, patriarchy, tradition. And Wilde shows us that this authority is not wise, moral, or thoughtful. It is rigid, absurd, and obsessed with surfaces.

Her horror at the handbag is not moral outrage. It is aesthetic disgust.

Wilde’s critique is clear:

Power does not require intelligence.

It requires confidence and convention.

5. Why the Ending Is Deliberately Hollow

Many readers ask why the play ends happily if Wilde is criticising society. The answer is simple: because society rewards compliance, not change.

No one grows. No one reforms. No one reflects deeply. The system remains intact. The ending is cheerful because the illusion has been successfully repaired.

That is Wilde’s final, cruel joke.

If he had ended the play tragically, society could dismiss it.

By ending it happily, he forces the audience to applaud their own exposure.

Final Truth Wilde Leaves Us With

Wilde is not asking us to be honest.

He is asking us to be aware.

Aware that morality can be performative.

Aware that respectability often masks emptiness.

Aware that society prefers comfortable lies to inconvenient truths.

The Importance of Being Earnest is not about being earnest at all.

It is about how seriously society takes nonsense, and how lightly it treats truth.

Wilde laughs, not because the world is funny,

but because it is pretending not to be ridiculous.

And that, for him, was the most honest response possible.

A Comedy of Manners, or a Polite Social Autopsy

The Importance of Being Earnest belongs to the long tradition of the Comedy of Manners, but Wilde does not merely follow the form. He perfects it, sharpens it, and then quietly laughs at it.

A comedy of manners does not concern itself with deep emotional suffering or heroic struggle. It observes how people behave in society, how they speak, flirt, deceive, judge, and perform respectability. The focus is not on what characters feel, but on how they are expected to act.

Wilde understood that Victorian England was already theatrical. Everyone was playing a role. He simply wrote the script.

In this play, manners are more important than morals. Etiquette replaces ethics. Being polite excuses being dishonest. This is why deception in Earnest never leads to punishment. The lies are delivered elegantly. They respect social rhythm. They do not disrupt tea.

The drawing room becomes Wilde’s courtroom. Conversation is the evidence. Epigrams are the weapons.

What makes Wilde’s comedy radical is its emotional lightness. He refuses tragedy. He refuses moral reform. By doing so, he exposes how superficial social outrage actually is. Society is not disturbed by dishonesty. It is disturbed by awkwardness.

Victorian manners demanded restraint, repression, and emotional control. Wilde turns those very restraints into comic material. Love is declared formally. Anger is expressed politely. Hostility is served with sugar.

Even rebellion, in this world, must be well-mannered.

And that is why the play feels effortless while doing serious damage. Wilde never breaks decorum. He uses decorum to show its emptiness.

The Comedy of Manners traditionally ends with reconciliation and marriage. Wilde keeps that convention intact, but empties it of moral satisfaction. The marriages at the end of Earnest are not earned through growth. They are approved through technical correctness.

In this sense, the play becomes a mirror held up to Victorian society, reflecting not its values, but its habits. And habits, Wilde suggests, are far more revealing than principles.

By laughing at these manners, Wilde invites the audience to recognise themselves. But he never demands change. That would be impolite.

He simply lets the laughter linger long enough to become uncomfortable.

ABS folds the scroll slowly, not because the comedy has ended, but because the joke has landed.

She smiles, knowing Wilde never mocked individuals, only the performances they mistook for virtue.

The laughter still lingers, light and dangerous, like truth wrapped in silk.

Names have triumphed over nature, manners over morals, and society has applauded itself.

Nothing has changed, and that was always the point.

Respectability stands intact, slightly ridiculous, entirely satisfied.

The handbag rests, the lies retire politely, and sincerity remains unnecessary.

ABS closes the scroll, aware that the audience is still laughing.

And somewhere, Wilde would approve.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance